Chaturbhuj Meher

From Wikipedia

Chaturbhuj Meher

Born 13 October 1935

Occupation Weaver

Awards Padma Shri

Odisha State Award

Chinta O Chetana National Award

Viswakarma Award

Priyadarshini Award

Website mehersonline

Chaturbhuj Meher is an Indian weaver, considered by many as one of the master weavers of the Tie-dye handloom tradition of Odisha. Born on 13 October 1935 at Sonepur in Odisha, he had formal education only up to school level but learned the traditional weaving craft to join Weavers' Service Centre as a Weaver. Vayan Vihar, a handloom factory and Handloom Research and Training Center, a research institute in Sonepur have been founded by him and he is known to have trained over 10,000 craftsmen.

Aishwarya Rai, former Miss World and Bollywood actor is reported to have worn one of Meher's Sonepuri Sari creations on her wedding day, gifted by her mother-in-law, Jaya Bachchan. He is a recipient of the Odisha State Award twice, in 1991 and 1995, as well as awards such as Chinta O Chetana National Award (1992), Viswakarma Rashtriya Puraskar (1997) and Priyadarshini Award (2005). The Government of India awarded him the fourth highest civilian honour of the Padma Shri, in 2005, for his contributions to Indian handloom sector.

3200 साल पहले एशिया महाद्वीप का नाम चमारद्वीप

Posted by surender12

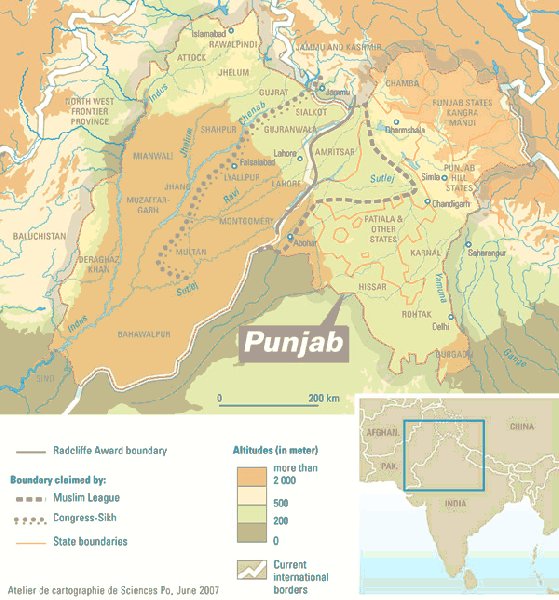

सभी मूल निवासियों के इतिहास का अध्ययन करने से पता चलता है कि किसी समय एशिया महाद्वीप को चमारद्वीप कहा जाता था। जो बाद में जम्बारद्वीप के नाम से जाना गया और कालांतर में वही जम्बारद्वीप, जम्बूद्वीप के नाम से प्रसिद्ध हुआ था। चमारद्वीप की सीमाए बहुत विशाल थी। चमारद्वीप की सीमाए अफ्गानिस्तान से श्री लंका तक, ऑस्ट्रेलिया, प्रायदीप और दक्षिण अफ्रीका तक फैली हुई थी। 3200 ईसा पूर्व जब यूरेशियन चमारद्वीप पर आये तो देश का विघटन शुरू हुआ। क्योकि हर कोई अपने आप को युरेशियनों से बचाना चाहता था। जैसे जैसे देश का विघटन हुआ, बहुत से प्रदेश चमारद्वीप से अलग होते गए और चमारद्वीप का नाम बदलता गया। भारत के नामों का इतिहास कोई ज्यादा बड़ा नहीं है परन्तु हर मूल निवासी को इस इतिहास का पता होना बहुत जरुरी है, तो ईसा से 3200 साल पहले एशिया महाद्वीप का नाम चमारद्वीप था, यूरेशियन भारत में आये तो जम्बारद्वीप हो हो गया, 485 ईसवी तक भारत का नाम जम्बूद्वीप था, 485 ईसवी में सिद्धार्थ बौद्ध ने मूल निवासियों के लिए क्रांति की, सभी मूल निवासियों को इकठ्ठा करने की कोशिश की। इस में सिद्धार्थ गौतम अर्थात बौद्ध धर्म को बहुत सफलता मिली थी। किन्तु युरेशियनों ने झूठे बौद्ध भिक्षु बन कर बौद्ध धर्म का विनाश कर दिया। इस प्रकार 600 या 800 ईसवी में भारत का नाम आर्यवर्त रखा गया। 1600 ईसवी अर्थात भक्ति काल तक भारत का नाम आर्यवर्त था। भारत का नाम किसी महान राजा भरत के नाम पर रखा गया है यह एक काल्पनिक कहानी है। असल में 1600 ईसवी में मनु नाम के एक यूरेशियन ब्राह्मण ने मनु समृति लिख कर फिर से भारत पर ब्राह्मणों अर्थात युरेशियनों का शासन स्थापित किया था। मनु के एक बेटे का नाम भरत था। उसी भरत के नाम पर आर्यवर्त को भारत कहा गया। आज़ादी के बाद भारत की संसद में एक प्रस्ताव पारित करके भारत का नाम इंडिया रख दिया गया।

अब समझ आया सारे मूल निवासी चमार कैसे हुए? अभी भी समझ में नहीं आया हो तो कृपया नीचे दिए गए लिंक पर क्लिक करें और पूरी पोस्ट पढ़े:

The Riddle of Rama and Krishna

– By Babasaheb Ambedkar

Quoted from: Appendix No.1 of Part 3 of the book

Riddles of Hinduism 1995

By Dr. Babasaheb B.R. Ambedkar

Ravana was a Buddhist and considered by Dalits as a great hero. He did so much for Sita, who herself had praised Ravana. But the Hindu scriptures have called him a Rakshasa attributing all evils to him. Not only that. Every year during the Ram lila. Ravana is burnt. Dalits have tolerated all of this. They have also tolerated the Ramayana TV serial ridiculing their other tribal hero, Hanuman, as a monkey.

The Riddles in Hinduism is a scholarly work by the greatest intellectual of India. The text of his writings on Rama and Krishna are based on Hindu scriptures.

THE RIDDLE OF RAMA AND KRISHNA

Rama is the hero of the Ramayana whose author is Valmiki. The story of the Ramayana is a very short one. Besides it is simple and in itself there is nothing sensational about it.

Rama is the son of Dasharatha, the king of Ayodhya, the modern Banares. Dasharatha had three wives, Kausalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra besides several hundred concubines. Kaikeyi had married Dasharatha on terms which were at the time of marriage unspecified and which Dasharatha was bound to fulfill whenever he was called upon by Kaikeyi to do so.

Dasharatha was childless for a long time. An heir to the throne was ardently desired by him. Seeing that he was unable to have a son with any of his three wives he decided to perform a Putreshti Yajna and called the sage Shrung at the sacrifice who prepared pandas and gave the three wives of Dasharatha to eat them. After they ate the pandas the three wives became pregnant and gave birth to sons. Kausalya gave birth to Rama, Kaikeyi gave birth to Bharatha and Sumitra gave birth to two sons, Laxman and Satrughana. In due course Rama was married to Sita.

When Rama came of age, Dasharatha thought of resigning the throne in favour of Rama and retiring from kingship. While this was being settled Kaikeyi raised the question of rendering her satisfaction of the terms on which she had married Dasharatha. On being asked to state her terms she demanded that her son Bharata should be installed on the throne in preference to Rama and that Rama should live in the forest for 12 years. Dasharatha, with great reluctance, agreed. Baharata became king of Ayodhya and Rama accompanied by his wife Sita and his step brother Laxman went to live in the forest.

Ravana, the king of Lanka, kidnapped Sita and took her away and kept her in his palace intending to make her one of his wives. Rama and Laxman than started search of Sita. On the way they meet Sugriva and Hanuman, two leading personages of the Vanara (monkey) race and formed friendship with them. With their help they marched on Lanka, defeated Ravana in the battle and rescued Sita. Rama returned with Laxman and Sita to Ayodhya. By the time twelve years had elapsed and the term prescribed by Kaikeyi was fulfilled, with the result that Bharata gave up the throne and in his place Rama became the king of Ayodhya.

Such is the brief outline of the story of the Ramayana as told by Valmiki.

There is nothing in this story to make Rama the object of worship. He is only a dutiful son. But Valmiki saw something extraordinary in Rama and that is why he undertook to compose the Ramayana. Valmiki asked Narada the following question:

Tell me Oh! Narada, who is the most accomplished man on earth at the present time?” And then he goes on to elaborate what he means by accomplished man. He defines his accomplished man as:

“Powerful, one who knows the secret of religion, one who knows gratitude, truthful, one who is ready to sacrifice his self interest even when in distress to fulfill a religious vow, virtuous in his conduct, eager to safeguard the interests of all, strong, pleasing in appearance with power of self-control, able to subdue anger, illustrious, with no jealousy for the prosperity of others, and in war able to strike terror in the hearts of Gods.”

Narada then asks for time to consider and after mature deliberation tells him that the only person who can be said to possess these virtues is Rama, the son of Dasharatha.

It is because of his virtues that Rama has come to be defied. But is Rama a worthy personality of deification? Let those who accept him as an object of worship as a God consider the following facts:

Rama’s birth is miraculous and it may be that the suggestion that he was born from a pinda prepared by the sage Shrung is an allegorical gloss to cover up the naked truth that he was begotten upon Kausalya by the sage Shrung, although the two did not stand in the relationship of husband and wife. In any case his birth, if not disreputable in its origin, is certainly unnatural.

There are other incidents connected with the birth of Rama the unsavory character of which it will be difficult to deny.

Valmiki starts his Ramayana by emphasizing the fact that Rama is an Avatar of Vishnu, and it is Vishnu who agreed to take birth as Rama and be the son of Dasharatha. The God Brahma came to know of this and felt that in order that this Rama Avatar of Vishnu be a complete success, arrangement shall be made that Rama shall have powerful associates to help him and cooperate with him. There were none existing then.

The Gods agreed to carry out the command to Brahma and engaged themselves in wholesale acts of fornication not only against Apsaras who were prostitutes, not only against the unmarried daughters of Yakshas and Nagas but also against the lawfully wedded wives of Ruksha, Vidhyadhar, Gandharvas, Kinnars and Vanaras and produced the Vanaras who became the associates of Rama.

Rama’s birth is thus accompanied by general debauchery if not in his case certainly in the case of his associates. His marriage to Sita is not above comment. According to Buddha Ramayana, Sita was the sister of Rama, both were the children of Dasharatha. The Ramayana of Valmiki does not agree with the relationship mentioned in Buddha Ramayana. According to Valmiki, Sita was the daughter of the king Janaka of Videha and therefore not a sister of Rama. This is not convincing for even according to Valmiki she is not the natural born daughter of Janaka but a child found by a farmer in his field while ploughing it and was presented by him to king Janaka and brought up by Janaka. It was therefore in a superficial sense that Sita could be said to be daughter of Janaka.

The story in the Buddha Ramayana is natural and not inconsistent with the Aryan rules of marriage. If the story is true, then Rama’s marriage to Sita is no ideal to be copied.

In another sense Rama’s marriage was not an ideal marriage which could be copied. One of the virtues ascribed to Rama is that he was monogamous. It is difficult to understand how such a notion could have become common. For it has no foundation in fact. Even Valmiki refers to the many wives of Rama. These were of course in addition to his many concubines. In this he was the true son of his nominal father Dasharatha who had not only the wives referred to above but many others.

Let us next consider his character as an individual and as a king.

In speaking of him as an individual, I will refer to only two incidents – one relating to his treatment of Vali and other relating to his treatment of his own wife Sita. First, let us consider the incident of Vali.

Vali and Sugriva were two brothers. They belonged to the Vanar race and came from a ruling family, which had its own kingdom the capital of which was Kishkindha. At the time when Sita was kidnapped by Ravana, Vali was reigning at Kishkindha. While Vali was on the throne he was engaged in a war with a Rakshasa by name Mayavi. In the personal combat between the two, Mayavi ran for his life. Both Vali and Sugriva pursued him. Mayavi entered into a deep cavity in the earth. Vali asked Sugriva to wait at the mouth of the cavity and he went inside. After sometime a flood of blood came from inside the cavity. Sugriva concluded that Vali must have been killed by Mayavi and came to Kishkindha and got himself declared king in place of Vali and made Hanuman his Prime Minister.

As a matter of fact, Vali was not killed. It was Mayavi who was killed by Vali. Vali came out of the cavity but did not find Sugriva there. He proceeded to Kishkindha and to his great surprise he found that Sugriva had proclaimed himself king. Vali naturally became enraged at this act of treachery on the part of his brother Sugriva and he had good ground to be. Sugriva should have ascertained, should not merely have assumed, that Vali was dead. Secondly, Vali had a son by name Angad whom Sugriva should have made the king as the ligitimate heir of Vali. He did neither of the two things. His was a clear case of usurpation. Vali drove out Sugriva and took back the throne. The two brothers became mortal enemies.

This occurred just after Ravana had kidnapped Sita. Rama and Laxman were wandering in search of her. Sugriva and Hanuman were wandering in search of friends who could help them regain the throne from Vali. The two parties met quite accidentally. After informing each other of their difficulties, a pact was arrived at between the two. It was agreed that Rama should help Sugriva to kill Vali and to establish him on the throne of Kishkinda. On the part of Sugriva and Hanuman it was agreed that they should help Rama to regain Sita. To enable Rama to fulfill his part of the pact it was planned that Sugriva should wear a garland around his neck as to be easily distinguishable to Rama from Vali and that while the duel was going on Rama should conceal himself behind a tree and then shoot an arrow at Vali and kill him. Accordingly a duel was arranged, Sugriva with a garland around his neck, while the duel was on, Rama, standing behind a tree, shot Vali with his arrow and opened the way for Surgiva to be the king of Kiskinda.

This murder of Vali is the greatest blot on the character of Rama. It was a crime which was thoroughly unprovoked, for Vali had no quarrel with Rama. It was a most cowardly act, for Vali was unarmed. It was a planned and premeditated murder.

Consider his treatment of his own wife Sita. With the army collected for him by Sugriva and Hanuman, Rama invades Lanka. There too he plays the same mean part as he did between the two brothers, Vali and Sugriva. He takes the help of Vibhishana, the brother of Ravana, promising him to kill Ravana and his son and place him on the vacant throne. Rama kills Ravana and his son Indrajit. The first thing Rama does after the fight was to give a descent burial to the dead body of Ravana. Thereafter he interested himself in the coronation of Vibhishana and it was after the coronation that he sends Hanuman to Sita to inform her that he, Laxman and Sugriva have killed Ravana.

Even when the coronation was over he did not go himself but he sent Hanuman. And what was the message he sent him with? He did not ask Hanuman to bring her. He asked him to inform her that he was hale and hearty. It was Sita who expressed to Hanuman her desire to see Rama. Rama did not go to see Sita, his own wife who was kidnapped and confined by Ravana for more than 10 months. Sita went to him and what did Rama say to Sita when he saw her? It would be difficult to believe any man with ordinary human kindness could address his wife in such dire distress as Ram did to Sita when he met her at Lanka if there was not the direct authority of Valmiki. This is how Rama addressed het:

“I have got you as a prize in a war after conquering my enemy, your captor. I have recovered my honour and punished my enemy. People have witnessed my military powers and I am glad my labours have been rewarded. I came here to kill Ravana and wash off the dishonour. I did not take this trouble for your sake.”

Could there be anything more cruel than this conduct of Rama towards Sita? He does not stop there. He proceeded to tell her:

“I suspect your conduct. You must have been spoiled by Ravana. Your very sight is revolting to me. Oh you daughter of Janaka! I allow you to go anywhere you like. I have nothing to do with you. I conquered you back and I am content for that was my object. I cannot think that Ravana would have failed to enjoy a woman as beautiful as you are.”

Quite naturally Sita calls Rama low and mean and tells him quite plainly that she would have committed suicide and saved him all this trouble if when Hanuman first came he had sent her a message that he had abandoned her on the ground that she was kidnapped. To give him no excuse Sita undertakes to prove her purity. She enters the fire and comes out unscathed. The Gods satisfied with this evidence, proclaim that she is pure. It is then that Rama agrees to take her back to Ayodhya.

And what does he do with her when he brings her back to Ayodhya? Of course, he became king and she became queen. But while Rama remained king, Sita ceased to be queen very soon. This incident reflects great infamy upon Rama. It is recorded by Valmiki in his Ramayana that some days after the coronation of Rama and Sita as king and queen, Sita conceived. Seeing that she was carrying some residents of evil disposition began to calumniate Sita suggesting that she was in Lanka and blaming Rama for taking such a woman back as his wife. This malicious gossip in the town was reported by Bhadra, the Court joker, to Rama. Rama evidently was stung by this calumny. He was overwhelmed with a sense of disgrace. This is quite natural. What is quite unnatural is the means he adopts of getting rid of this disgrace. To get rid of this disgrace he takes the shortest cut and the swiftest means – namely to abandon her, a woman in a somewhat advanced state of pregnancy in a jungle, without friends, without provision, without even notice – in a most treacherous manner. There is no doubt that the idea of abandoning Sita was not sudden and had not occurred to ram on the spur of the moment. The genesis of the idea, the developing of it and the plan of executing are worth some detailed mention.

When Bhadra reports to him the gossip about Sita which had spread in the town, Rama calls his brothers and tells them of his feelings. He tells them Sita’s purity and chastity was proved in Lanka, that Gods had vouched for it and that he absolutely believed in her innocence, purity and chastity. “All the same the public are calumniating Sita and are blaming me and putting me to shame. No one can tolerate such disgrace. Honour is a great asset; Gods as well as great men strive to maintain it. I cannot bear this dishonour and disgrace. To save myself from such dishonour and disgrace I shall be ready even to abandon you. Don’t think I shall hesitate to abandon Sita.”

This shows that he was making up his mind to abandon Sita as the easiest way of saving himself from public calumny without considering whether the way was fair or foul. The life of Sita simply did not count. What counted was his own personal name and fame. He of course does not take the manly course of defending his wife and stopping the gossip, which as a king he could have done and which as a husband who was convinced of his wife’s innocence he was supposed to do. He yielded to the public gossip and there are not wanting Hindus who use this as ground to prove that Rama was a democratic king when others could equally well say that he was a weak and cowardly monarch. Be that as it may that diabolical plan of saving his name and his fame he discloses to his brother but not to Sita, the only person who was affected by it and the only person who was entitled to have notice of it. But she is kept entirely in the dark. Rama keeps it away from Sita as a closely guarded secret and was waiting for an opportunity to put his plan into action. Eventually the cruel fate of Sita gives him the opportunity he was waiting for. Women who are carrying exhibit all sorts of cravings for all sorts of things. Rama knew of this. So one day he asked Sita if there was anything for which she was craving. She replied that she would like to live in the vicinity of the Ashrama of a sage on the bank of the river Ganges and live on fruits and roots at least for one night. Rama simply jumped at the suggestion of Sita and said, “Be easy my dear, I shall see that you are sent there tomorrow”. Sita treats this as an honest promise. But what does Rama do? He thinks it is a good opportunity for carrying out his plan of abandoning Sita. Accordingly he called his brothers to a secret conference and disclosed to them his determination to use this desire of Sita as the opportunity to carry out the plan of abandoning her. He tells his brothers not to intercede on behalf of Sita, and warns them that if they came in his way he would look upon them as his enemies. Then he tells Laxman to take Sita in a chariot next day to the Ashram in the jungle on the bank of the river Ganges and to abandon her there. Laxman did not know how he could muster courage to tell Sita what was decided by Rama. Sensing his difficulty Rama informs Laxman that Sita had already expressed her desire to spend some time in the vicinity of an Ashram on the bank of the river and eased the mind of Laxman. This confabulation took place at night. Next morning Laxman asked Sumanta to yoke the horses to the chariot. Sumanta informs Laxman of having already done so. Laxman then goes into the palace and meets Sita and reminds her of her having expressed the desire to pass some days in the vicinity of an Ashrama and Rama having promised to fulfill the same and tells her of his having been charged by Rama to do the needful in the matter. He points to her the chariot waiting there and says, “Let us go!” Sita jumps into the chariot with her heart full of gratitude to Rama. With Laxman as her companion and Sumanta as coachman, the chariot proceeds to its appointed place. At last, they were on the bank of the Ganges and were ferried across by the fishermen. Laxman fell at Sita’s feet, and with hot tears flowing from his eyes he said, “Pardon me, O, blameless queen, for what I am doing. My orders are to abandon you here, for the people blame Rama for keeping you in his house”.

Sita, abandoned by Rama and left to die in a jungle, went for shelter to the Ashrama of Valmiki, which was near about. Valmiki gave her protection and kept her in his Ashram. There in course of time, Sita gave birth to twin sons, called Kusa and Lava. The three lived with Valmiki. Valmiki brought up the boys and taught them to sing the Ramayana which he had composed. For 12 years the boys lived in the forest in the Ashrama of Valmiki not far from Ayodhya where Rama continued to rule. Never once in those 12 years this ‘model husband and loving father’ cared to inquire what had happened to Sita – whether she was living or whether she was dead. Twelve years after Rama meets Sita in a strange manner. Rama decided to perform a Yagna and issued an invitation to all the Rishis to attend and take part. For reasons best known to Rama himself no invitation was issued to Valmiki although his Ashram was near to Ayodhya. But Valmiki came to the Yagna of his own accord accompanied by the two sons of Sita introducing them as his disciples. While the Yagna was going on the two boys were used to perform recitations of Ramayana in the presence of the Assembly. Rama was very pleased and made inquiries, and he was informed that they were the sons of Sita. It was then he remembered Sita and what does he do then? He does not send for Sita. He calls these innocent boys who knew nothing about their parents’ sin, who were the only victims of a cruel destiny, to tell Valmiki that if Sita was pure and chaste she could present herself in the Assembly to take a vow and thereby remove the calumny cast against herself and himself. This is a thing she had once done in Lanka. This is a thing she could have been asked to do again before she was sent away. There was no promise that after this vindication of her character Rama was prepared to take her back. Valmiki brings her to the Assembly. When she was in front of Rama, Valmiki said, “O, son of Dashratha, here is Sita whom you abandoned in consequence of public disapprobation. She will now swear her purity if permitted by you. Here are your twin-born sons raised up by me in my hermitage”. “I know”, said Rama, “that Sita is pure and that these are my sons. She performed an ordeal in Lanka in proof of her purity and therefore I took her back. But people here have doubts still, and let Sita perform an ordeal here that all these Rashis and people may witness it”.

With eyes cast down on the ground and with hands folded Sita swore “As I never thought out of anyone except Rama even in my mind, let mother Earth open and bury me. As I always loved Rama in words, in thoughts, and in deed, let mother Earth open and bury me!” As she uttered the oath, the earth verily opened and Sita was carried away inside seated on a golden simhasana (throne). Heavenly flowers fell on Sita’s head while the audience looked on as in a trance.

That means that Sita preferred to die rather than return to Rama who had behaved no better than a brute.

Such is the tragedy of Sita and the crime of Rama the God.

Let me throw some search light on Rama the King.

Rama is held out as an ideal King. But can that conclusion be said to be found in fact?

As a matter of fact Rama never functions as a king. He was a normal King. The administration, as Valmiki, states, was entrusted to Bharata, his brother. He had freed himself from the cares and worries about his kingdom and subjects.

Valmiki has very minutely described the daily life of Rama after he became King. According to that accounts, the day was divided into two parts, up to forenoon and afternoon. From morning to forenoon he was engaged in performing religious rites and ceremonies and offering devotion. The afternoon he spent alternately in the company of Court jesters and in the Zenana. When he got tired of jesters he went back to the Zenana. Valmiki also gives a detailed description of how Rama spent his life in the Zenana. This Zenana was housed in a park called Ashoka Vana. There Rama used to tale his meals. The food, according to Valmiki, consisted of all kinds of delicious viands. They included flesh and fruits and liquor. Rama was not a teetotaler. He drank liquor copiously and Valmiki records that Rama saw to it that Sita joined with him in his drinking bouts. From the description of the Zenana of Rama as given by Valmiki it was by no means a mean thing. There were Apsaras, Uraga and Kinnari accomplished in dancing and singing. There were other beautiful women brought from different parts. Rama sat in the midst of these women drinking and dancing. They pleased Rama and Rama garlanded them. Valmiki calls Ram as a ‘Prince among women’s men’. This was not a day’s affair. It was a regular course of his life.

As has already been said Rama never attended to public business. He never observed the ancient rule of Indian kings of hearing the wrongs of his subjects and attempting to redress them. Only one occasion has been recorded by Valmiki when he personally heard the grievance of his subjects. But unfortunately the occasion turned out to be a tragic one. He took upon himself to redress the wrong but in doing so committed the worst crime that history has ever recorded.

The incident is known as the murder of Sambuka, the Shudra. It is said by Valmiki that in Rama’s reign there were no premature deaths in his kingdom. It happened, however, that a certain Brahman’s son died in a premature death. The bereaved father carried his body to the gate of the king’s palace, and placing it there, cried aloud and bitterly reproached Rama for the death of his son, saying that it must be the consequence of some sin committed within his realm, and that the king himself was guilty if he did not punish it; and finally threatened to end his life there by sitting on a dharana (hunger-strike) against Rama unless his son was restored to life. Rama thereupon consulted his council of eight learned Rishis, and Narada amongst them told Rama that some Shudra among his subjects must have been performing Tapasya (ascetic exercises), and thereby going against Dharma (sacred law), for according to it, the practice of Tapasya was proper to the twice-born alone, while the duty of the Shudras consisted only in the service of the “twice-born”. Rama was thus convinced that it was the sin committed by a Shudra in transgressing Dharma in that manner, which was responsible for the death of the Brahmin boy.

So, Rama mounted his aerial car and scoured the countryside for the culprit. At last, in a wild region far away to the south he espied a man practicing rigorous austerity of a certain kind. He approached the man, and with no more ado than to enquire of him and inform himself that he was a Shudra, by name Sambuka who was practicing Tapasya with a view to going to heaven in his own earthly person and without so much as a warning, expostulation or the like addressed to him, cut off his head. And lo and behold! At that very moment the dead Brahman boy in distant Ayodhya began to breathe again. Here in the wilds the Gods rained flowers on the king from their joy at his having prevented a Shudra from gaining admission to their celestial abode through the power of the Tapasya which he had no right to perform. They also appeared before Rama and congratulated him on his deed. In answer to his prayer to them to revive the dead Brahman boy lying at the palace gate in Ayodhya, they informed him that he had already come to life. They then departed. Rama thence proceeded to the Ashrama, which was nearby, of the sage Agastya, who commended the step he had taken with Sambuka, and presented him with a divine bracelet. Rama then returned to his capital.

Such is Rama.

सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस

–एस. आर. दारापुरी, राष्ट्रीय प्रवक्ता, आल इंडिया पीपुल्स फ्रंट

31 जुलाई देश भर में “सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस” के रूप में मनाया जाता है. इस दिन दिल्ली, नागपुर और शिमला नगरपालिका में सफाई कर्मचारियों को छुट्टी होती है. इस दिन सफाई कर्मचारी इकट्ठा हो कर अपनी समस्यायों पर विचार-विमर्श करते हैं और अपनी मांगें सामूहिक रूप से उठाते हैं.

सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस का इतिहास यह है कि 29 जुलाई, 1957 को दिल्ली म्युनिसिपल कमेटी के सफाई कर्मचारियों ने अपने वेतन तथा कुछ काम सम्बन्धी सुविधायों की मांग को लेकर हड़ताल शुरू की थी. उसी दिन केन्द्रीय सरकार के कर्मचारियों की फेडरेशन ने भी हड़ताल करने की चेतावनी दी थी. पंडित नेहरु उस समय भारत के प्रधान मंत्री थे. उन्होंने केन्द्रीय सरकार के कर्मचारियों तथा सभी हड़ताल करने वालों को कड़े शब्दों में चेतावनी दी कि उनकी हड़ताल को सख्ती से दबा दिया जायेगा.

30 जुलाई को नई दिल्ली सफाई कर्मचारियों की हड़ताल शुरू हो गयी नगरपालिका ने हड़ताल को तोड़ने के लिए बाहर से लोगों को भर्ती करके काम चलाने की कोशिश की. उधर सफाई कर्मचारियों ने एक तरफ तो कूड़ा ले जाने वाली गाड़ियों को नए भर्ती हुए कर्मचारियों को काम करने के लिए जाने से रोका और दूसरी ओर काम करने वालों से जाति के नाम पर अपील की कि वे उनके संघर्ष को सफल बनायें. हुमायूँ रोड, काका नगर, निजामुद्दीन आदि के करीब हड़ताली तथा नए भर्ती सफाई कर्मचारियों की झड़पें भी हुयीं.

31 जुलाई को दोपहर तीन बजे के करीब भंगी कालोनी रीडिंग रोड से नए भर्ती किये गए कर्मचारियों को लारियों में ले जाने की कोशिश की गयी. सफाई कर्मचारियों ने इसे रोकने की कोशिश की. पुलिस की सहायता से एक लारी निकाल ली गयी. परंतु जब दूसरी लारी निकाली जाने लगी तो हड़ताल करने वाले कर्मचारियों ने ज्यादा जोर से इस का विरोध किया. पुलिस ने टिमलू नाम के एक कर्मचारी को बुरी तरह से पीटना शुरू किया. उस पर भीड़ उतेजित हो गयी और किसी ने पुलिस पर पत्थर फेंके. उस समय मौके पर मौजूद डिप्टी एस.पी. ने भीड़ पर गोली चलाने का आदेश दे दिया. बस्ती के लोगों का कहना है कि पुलिस ने बस्ती के अन्दर आ कर लोगों को मारा और गोलियां चलायीं. गोली चलाने के पहले न तो कोई लाठी चार्ज किया गया और न ही आंसू गैस ही छोड़ी गयी. कितनी गोलियां चलाई गयीं पता नहीं. पुलिस का कहना था कि 13 गोलियां चलायी गयीं.

इस गोली कांड में भूप सिंह नाम का एक नवयुवक मारा गया जो कि सफाई कर्मचारी तो नहीं था परन्तु वहां पर मेहमानी में आया हुआ था. जो नगरपालिका सफाई कर्चारियों की 30 जुलाई तक कोई भी मांग मानने को तैयार नहीं थी, हड़ताल शुरू होने के बाद मानने को तैयार हो गयी. हड़ताल के दौरान पुलिस द्वारा गोली चलाये जाने और एक आदमी की मौत हो जाने के कारण सफाई कर्मचारियों में गुस्सा और जोश बढ़ा जो भयानक रूप ले सकता था. बहुत से लोगों ने हमदर्दी जताई और आहिस्ता-आहिस्ता लोग इस घटना को भूलने लगे.

भंगी कालोनी में रहने वाले कर्मचारी नौकरी खो जाने के डर से किसी भी गैर कांग्रेसी राजनीतिक पार्टी को नजदीक नहीं आने देते थे. उधर कर्मचारी इस घटना को भुलाना भी नहीं चाहते थे. वे गोली का शिकार हुए नौजवान भूप सिंह की मौत को अधिक महत्व देते थे, उस की मौत के कारणों को या शासकों के रवैये को नहीं. उनकी भावनायों को ध्यान में रखते हुए इस बस्ती में रहने वाले नेताओं ने भूप सिंह की बर्सी मनाने की प्रथा शुरू कर दी. 1957 के बाद हर वर्ष पंचकुइआं रोड स्थित भंगी कालोनी में “भूप सिंह शहीदी दिवस” मनाया जाने लगा और भूप सिंह को इस आन्दोलन का हीरो बनाया जाने लगा. भूप सिंह की बड़ी सी तस्वीर बाल्मीकि मंदिर से जुड़े कमरे में लगायी गयी. इस मीटिंग में हर वर्ष भूप सिंह को श्रदांजलि पेश की जाती है.

बाबा साहेब आंबेडकर की बड़ी इच्छा थी कि समूचे भारत के सफाई कर्मचारियों को एक मंच पर इकट्ठा किया जाये. उनकी एक देशव्यापी संस्था बनायीं जाये जो उनके उत्थान और प्रगति केलिए संघर्ष करे और उन्हें गंदे पेशे तथा गुलामी से निकाल सके. उन्होंने 1942 से 1946 तक जब वे वाईसराय की एग्जीक्यूटिव कोंसिल के श्रम सदस्य थे, वे उनकी राष्ट्रीय स्तर पर ट्रेड यूनियन बनाना चाहते थे ताकि वे अपने अधिकारों के लिए संगठित तौर पर लड़ सकें।

उन्होंने सफाई मजदूरों की समस्याओं के अध्ययन के लिए एक समिति भी बनायीं थी. दरअसलबाबा साहेब भंगियों से झाड़ू छुड़वाना चाहते थे और इसी लिए उन्होंने “भंगी झाड़ू छोडो” का नारा भी दिया था.

सफाई कर्मचारियों पर सब से अधिक प्रभाव गाँधी जी, कांग्रेस और हिन्दू राजनेताओं और धार्मिक नेताओं का रहा है. उन्होंने एक ओर तो सफाई कर्मचारियों को बाबा साहेब के स्वतंत्र आन्दोलन से दूर रखा और दूसरी ओर उन्हें अनपढ़, पिछड़ा, निर्धन और असंगठित रखने का प्रयास किया है ताकि वे सदा के लिए हिंदुओं पर निर्भर रहें, असंगठित रहें और पखाना साफ़ करने और कूड़ा ढोने का काम करते रहें. दूसरी ओर उनकी संस्थाओं को स्वंतत्र और मज़बूत बनने से रोका. उनकी लगाम हमेशा कांग्रेसी हिन्दुओं के हाथ में रही है.

सफाई कर्मचारियों में हमेशा से संगठन का अभाव रहा है क्योंकि बाल्मीकि या सुपच के नाम से समूचे भारत के सफाई कर्मचारियों को एक मंच पर इकट्ठा नहीं किया जा सकता है. ऐसा करने से उन में जातिगत टकराव का भय रहता है. अतः सफाई कर्मचारियों को बतौर “सफाई कर्मचारी”संगठित करना ज़रूरी है. इसी उद्देश्य से “अम्बेडकर मिशन सोसाइटी” जिस की स्थापना श्रीभगवान दास जी ने की थी, ने 1964 में यह तय किया कि “मजदूर दिवस” की तरह दिल्ली में भी“सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस” मनाया जायेगा ताकि उस दिन सफाई कर्मचारी अपनी समस्याओं और मांगों पर विचार विमर्श कर सकें और उन्हें संगठित रूप से उठा सकें. धीरे धीरे भारत के अन्य शहरों में भी 31 जुलाई को स्वीपर- डे अथवा सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस के नाम से मनाया जाने लगा. दिल्ली के बाद नागपुर पहला शहर है जहाँ पर 1978 के बाद से बाकायदा हर वर्ष स्वीपर-डेपब्लिक जलसे के तौर पर मनाया जाता है. इस दिन वहां पर अपने अधिकारों के लिए संघर्ष करने, दुर्घटनाओं तथा अपनी सेवाकाल के दौरान मरने वाले सफाई कर्मचारियों को श्रदांजलि पेश की जाती है और अन्य समस्याओं के समाधान के लिए विचार विमर्श किया जाता है. प्रस्ताव पास करके सरकार को भेजे जाते हैं और सफाई कर्मचारियों की उन्नति और प्रगति के लिए प्रोग्राम बनाये जाते हैं.

सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस कैसे मनाएं?

भगवान दास जी ने अपनी पुस्तक “सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस 31, जुलाई” में “सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस कैसे मनाएं?” में इसे सार्थक रूप से मनाने पर चर्चा में कहा है कि इसे बाल दिवस, शिक्षक दिवस और मजदूर दिवस की तरह मनाया जाना चाहिए. उन्होंने आगे कहा है कि इस दिन जलसे में उनकी व्यवसायिक, आर्थिक तथा सामाजिक व्यवस्था और शिक्षा आदि समस्याओं पर चर्चा करना उचित होगा. शिक्षा के प्रसार खास करके लड़कियों तथा महिलायों की शिक्षा पर जोर दिया जानाचाहिए. शिक्षा में सहायता के ज़रूरतमंद छात्र-छात्राओं को पुरुस्कार, संगीत तथा चित्रकारी, मूर्ति कला तथा खेलों को प्रोत्साहन देने तथा छोटे परिवार, स्वास्थ्य और नशा उन्मूलन पर जोर दिया जाना चाहिए. इस जलसे में मंत्रियों और बाहरी नेतायों को नहीं बुलाया जाना चाहिए. बाबा साहेब तथा अन्य महापुरुषों के जीवन संघर्ष आदि से लोगों को परिचित कराया जाना चाहिए ताकि उन्हें इस से प्रेरणा मिले और उनमें साहस एवं उत्साह बढ़े और वे खुद आगे की ओर बढ़ने की कोशिशकरें.

वास्तव में सफाई कर्मचारी दिवस को कर्मचारियों में संगठन-जागृति, शिक्षा और उत्थान के लिए पूरी तरह से उपयोगी त्यौहार के रूप में मनाया जाना चाहिए क्योंकि वे ही सब से अधिक शोषित, घृणित और पिछड़ा मजदूर वर्ग है.

Ambedkar wrote on why Brahmins started worshipping the cow and gave up eating beef

Courtsey: Sabrang

02 Aug 2016

It was a strategy, wrote the father of Indian Constitution, to vanquish Buddhism.

BOOK EXCERPT

Courtesy: Scroll.in

As we witness yet another incident of violence in the name of stopping cow-slaughter by groups of vigilantes known as gau-rakshaks, we revisit BR Ambedkar’s 1948 work The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables?, which grapples with many of the issues that continue to plague India even today.

What is the cause of the nausea which the Hindus have against beef-eating? Were the Hindus always opposed to beef-eating? If not, why did they develop such a nausea against it? Were the Untouchables given to beef-eating from the very start? Why did they not give up beef-eating when it was abandoned by the Hindus? Were the Untouchables always Untouchables? If there was a time when the Untouchables were not Untouchables even though they ate beef why should beef-eating give rise to Untouchability at a later-stage? If the Hindus were eating beef, when did they give it up? If Untouchability is a reflex of the nausea of the Hindus against beef-eating, how long after the Hindus had given up beef-eating did Untouchability come into being?Ambedkar's conclusions, based on an analysis of various religious texts, will seem more than deeply ironical to anyone who studies contemporary India, for the father of Indian Constitution argued that Brahmins who once had no compunctions against slaughter of animals, including cows, and were the greatest beef-eaters themselves, not only gave up beef-eating but also started worshipping the cow as a deliberate strategy.

The clue to the worship of the cow is to be found in the struggle between Buddhism and Brahmanism and the means adopted by Brahmanism to establish its supremacy over Buddhism.Earlier in the book, Ambedkar introduces the concept of Broken Men, whom he describes as follows:

In a tribal war it often happened that a tribe instead of being completely annihilated was defeated and routed. In many cases a defeated tribe became broken into bits. As a consequence of this there always existed in Primitive times a floating population consisting of groups of Broken tribesmen roaming in all directions.He also makes the assumption that

“Untouchables are Broken Men belonging to a tribe different from the tribe comprising the village community.”Ambedkar’s third assumption is that

“Broken Men were the followers of Buddhism and did not care to return to Brahmanism when it became triumphant over Buddhism”. What follows are excerpts from Chapter 9 to 14:

The Broken Men hated the Brahmins because the Brahmins were the enemies of Buddhism and the Brahmins imposed untouchability upon the Broken Men because they would not leave Buddhism. On this reasoning it is possible to conclude that one of the roots of untouchability lies in the hatred and contempt which the Brahmins created against those who were Buddhist.

Can the hatred between Buddhism and Brahmanism be taken to be the sole cause why Broken Men became Untouchables? Obviously, it cannot be. The hatred and contempt preached by the Brahmins was directed against Buddhists in general and not against the Broken Men in particular. Since untouchability stuck to Broken Men only, it is obvious that there was some additional circumstance which has played its part in fastening untouchability upon the Broken Men. What that circumstance could have been? We must next direct our effort in the direction of ascertaining it.]

Beef-eating as the root of Untouchability

[...]The Census Returns [of 1910] show that the meat of the dead cow forms the chief item of food consumed by communities which are generally classified as untouchable communities. No Hindu community, however low, will touch cow’s flesh. On the other hand, there is no community which is really an Untouchable community which has not something to do with the dead cow. Some eat her flesh, some remove the skin, some manufacture articles out of her skin and bones.

From the survey of the Census Commissioner, it is well established that Untouchables eat beef. The question however is: Has beef-eating any relation to the origin of Untouchability? Or is it merely an incident in the economic life of the Untouchables?

Can we say that the Broken Men to be treated as Untouchables because they ate beef? There need be no hesitation in returning an affirmative answer to this question. No other answer is consistent with facts as we know them.

In the first place, we have the fact that the Untouchables or the main communities which compose them eat the dead cow and those who eat the dead cow are tainted with untouchability and no others. The co-relation between untouchability and the use of the dead cow is so great and so close that the thesis that it is the root of untouchability seems to be incontrovertible.

In the second place if there is anything that separates the Untouchables from the Hindus, it is beef-eating. Even a superficial view of the food taboos of the Hindus will show that there are two taboos regarding food which serve as dividing lines.

There is one taboo against meat-eating. It divides Hindus into vegetarians and flesh eaters. There is another taboo which is against beef eating. It divides Hindus into those who eat cow’s flesh and those who do not. From the point of view of untouchability the first dividing line is of no importance. But the second is. For it completely marks off the Touchables from the Untouchables.

The Touchables whether they are vegetarians or flesh-eaters are united in their objection to eat cow’s flesh. As against them stand the Untouchables who eat cow’s flesh without compunction and as a matter of course and habit.

In this context it is not far-fetched to suggest that those who have a nausea against beef-eating should treat those who eat beef as Untouchables. There is really no necessity to enter upon any speculation as to whether beef-eating was or was not the principal reason for the rise of Untouchability.

This new theory receives support from the Hindu Shastras. The Veda Vyas Smriti contains the following verse which specifies the communities which are included in the category of Antyajas and the reasons why they were so included

“The Charmakars (Cobbler), the Bhatta (Soldier), the Bhilla, the Rajaka (washerman), the Puskara, the Nata (actor), the Vrata, the Meda, the Chandala, the Dasa, the Svapaka, and the Kolika – these are known as Antyajas as well as others who eat cow’s flesh.”Generally speaking, the Smritikars never care to explain the why and the how of their dogmas. But this case is exception. For in this case, Veda Vyas does explain the cause of untouchability. The clause “as well as others who eat cow’s flesh” is very important. It shows that the Smritikars knew that the origin of untouchability is to be found in the eating of beef.

The dictum of Veda Vyas must close the argument. It comes, so to say, straight from the horse’s mouth and what is important is that it is also rational for it accords with facts as we know them.

The new approach in the search for the origin of Untouchability has brought to the surface two sources of the origin of Untouchability. One is the general atmosphere of scorn and contempt spread by the Brahmins against those who were Buddhists and the second is the habit of beef-eating kept on by the Broken Men.

As has been said the first circumstance could not be sufficient to account for stigma of Untouchability attaching itself to the Broken Men. For the scorn and contempt for Buddhists spread by the Brahmins was too general and affected all Buddhists and not merely the Broken Men.

The reason why Broken Men only became Untouchables was because in addition to being Buddhists they retained their habit of beef-eating which gave additional ground for offence to the Brahmins to carry their new-found love and reverence to the cow to its logical conclusion.

We may therefore conclude that the Broken Men were exposed to scorn and contempt on the ground that they were Buddhists, and the main cause of their Untouchability was beef-eating.

[…]

Did the Hindus never eat beef?

[...] The adjective Aghnya applied to the cow in the Rig Veda means a cow that was yielding milk and therefore not fit for being killed. That the cow is venerated in the Rig Veda is of course true. But this regard and venerations of the cow are only to be expected from an agricultural community like the Indo-Aryans. This application of the utility of the cow did not prevent the Aryan from killing the cow for purposes of food. Indeed the cow was killed because the cow was regarded as sacred. As observed by Mr Kane:

"It was not that the cow was not sacred in Vedic times, it was because of her sacredness that it is ordained in the Vajasaneyi Samhita that beef should be eaten."That the Aryans of the Rig Veda did kill cows for purposes of food and ate beef is abundantly clear from the Rig Veda itself. In Rig Veda (X. 86.14) Indra says:

"They cook for one 15 plus twenty oxen". The Rig Veda (X.91.14) says that for Agni were sacrificed horses, bulls, oxen, barren cows and rams. From the Rig Veda (X.72.6) it appears that the cow was killed with a sword or axe.

[...] The correct view is that the testimony of the Satapatha Brahmana and the Apastamba Dharma Sutra in so far as it supports the view that Hindus were against cow-killing and beef-eating, are merely exhortations against the excesses of cow-killing and not prohibitions against cow-killing.

Indeed the exhortations prove that cow-killing and eating of beef had become a common practice. That notwithstanding these exhortations cow-killing and beef-eating continued. That most often they fell on deaf ears is proved by the conduct of Yajnavalkya, the great Rishi of the Aryans. ... After listening to the exhortation this is what Yajnavalkya said :

"I, for one, eat it, provided that it is tender"That the Hindus at one time did kill cows and did eat beef is proved abundantly by the description of the Yajnas given in the Buddhist Sutras which relate to periods much later than the Vedas and the Brahmanas.

The scale on which the slaughter of cows and animals took place was collosal. It is not possible to give a total of such slaughter on all accounts committed by the Brahmins in the name of religion...

Why did non-Brahmins give up beef-eating?

[...]

Examining the legislation of Asoka the question is: Did he prohibit the killing of the cow? On this issue there seem to be a difference of opinion... Asoka had no particular interest in the cow and owed no special duty to protect her against killing. Asoka was interested in the sanctity of all life human as well as animal. He felt his duty to prohibit the taking of life where taking of life was not necessary. That is why he prohibited slaughtering animal for sacrifice which he regarded as unnecessary and of animals which are not utilised nor eaten which again would be want on and unnecessary.

That he did not prohibit the slaughter of the cow in specie may well be taken as a fact which for having regard to the Buddhist attitude in the matter cannot be used against Asoka as a ground for casting blame.

Coming to Manu there is no doubt that he too did not prohibit the slaughter of the cow. On the other hand he made the eating of cow's flesh on certain occasions obligatory.This may be a novel theory but it is not an impossible theory. As the French author, Gabriel Tarde has explained that culture within a society spreads by imitation of the ways and manners of the superior classes by the inferior classes.

This imitation is so regular in its flow that its working is as mechanical as the working of a natural law. Gabriel Tarde speaks of the laws of imitation. One of these laws is that the lower classes always imitate the higher classes. This is a matter of such common knowledge that hardly any individual can be found to question its validity.

That the spread of the cow-worship among and cessation of beef-eating by the non-Brahmins has taken place by reason of the habit of the non-Brahmins to imitate the Brahmins who were undoubtedly their superiors is beyond dispute.Of course there was an extensive propaganda in favour of cow-worship by the Brahmins. The Gayatri Purana is a piece of this propaganda. But initially it is the result of the natural law of imitation. This, of course, raises another question:

Why did the Brahmins give up beef-eating?

What made the Brahmins become vegetarians?

[...]

[T]here was a time when the Brahmins were the greatest beef-eaters... In a period overridden by ritualism there was hardly a day on which there was no cow sacrifice to which the Brahmin was not invited by some non-Brahmin. For the Brahmin every day was a beef-steak day. The Brahmins were therefore the greatest beef-eaters. The Yajna of the Brahmins was nothing but the killing of innocent animals carried on in the name of religion with pomp and ceremony with an attempt to enshroud it in mystery with a view to conceal their appetite for beef. Some idea of this mystery pomp and ceremony can be had from the directions contained in the Atreya Brahamana touching the killing of animals in a Yajna...

[F]or generations the Brahmins had been eating beef. Why did they give up beef-eating? Why did they, as an extreme step, give up meat eating altogether and become vegetarians? It is two revolutions rolled into one.

As has been shown it has not been done as a result of the preachings of Manu, their Divine Law-maker. The revolution has taken place in spite of Manu and contrary to his directions. What made the Brahmins take this step? Was philosophy responsible for it? Or was it dictated by strategy?...

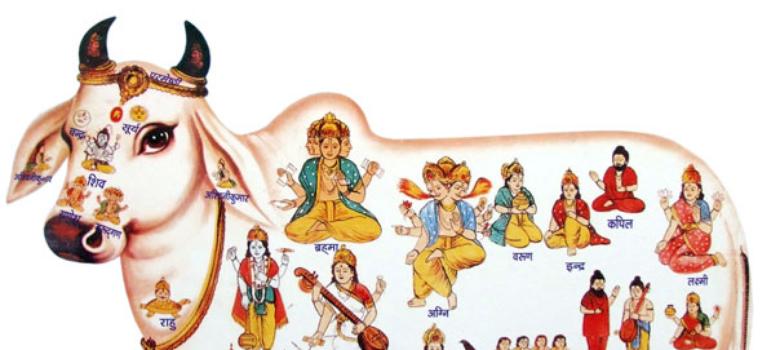

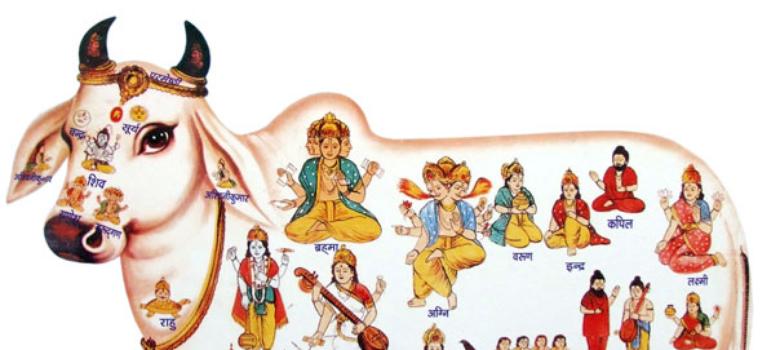

To my mind, it was strategy which made the Brahmins give up beef-eating and start worshipping the cow. The clue to the worship of the cow is to be found in the struggle between Buddhism and Brahmanism and the means adopted by Brahmanism to establish its supremacy over Buddhism.

The strife between Buddhism and Brahmanism is a crucial fact in Indian history. Without the realisation of this fact, it is impossible to explain some of the features of Hinduism. Unfortunately students of Indian history have entirely missed the importance of this strife. They knew there was Brahmanism. But they seem to be entirely unaware of the struggle for supremacy in which these creeds were engaged and that their struggle, which extended for 400 years has left some indelible marks on religion, society and politics of India.

This is not the place for describing the full story of the struggle. All one can do is to mention a few salient points. Buddhism was at one time the religion of the majority of the people of India. It continued to be the religion of the masses for hundreds of years. It attacked Brahmanism on all sides as no religion had done before.

Brahmanism was on the wane and if not on the wane, it was certainly on the defensive. As a result of the spread of Buddhism, the Brahmins had lost all power and prestige at the Royal Court and among the people.

They were smarting under the defeat they had suffered at the hands of Buddhism and were making all possible efforts to regain their power and prestige. Buddhism had made so deep an impression on the minds of the masses and had taken such a hold of them that it was absolutely impossible for the Brahmins to fight the Buddhists except by accepting their ways and means and practising the Buddhist creed in its extreme form.

After the death of Buddha his followers started setting up the images of the Buddha and building stupas. The Brahmins followed it. They, in their turn, built temples and installed in them images of Shiva, Vishnu and Ram and Krishna etc – all with the object of drawing away the crowd that was attracted by the image worship of Buddha.

That is how temples and images which had no place in Brahmanism came into Hinduism.

The Buddhists rejected the Brahmanic religion which consisted of Yajna and animal sacrifice, particularly of the cow. The objection to the sacrifice of the cow had taken a strong hold of the minds of the masses especially as they were an agricultural population and the cow was a very useful animal.

The Brahmins in all probability had come to be hated as the killer of cows in the same way as the guest had come to be hated as Gognha, the killer of the cow by the householder, because whenever he came a cow had to be killed in his honour. That being the case, the Brahmins could do nothing to improve their position against the Buddhists except by giving up the Yajna as a form of worship and the sacrifice of the cow.

That the object of the Brahmins in giving up beef-eating was to snatch away from the Buddhist Bhikshus the supremacy they had acquired is evidenced by the adoption of vegetarianism by Brahmins.

Why did the Brahmins become vegetarian? The answer is that without becoming vegetarian the Brahmins could not have recovered the ground they had lost to their rival namely Buddhism.

In this connection it must be remembered that there was one aspect in which Brahmanism suffered in public esteem as compared to Buddhism. That was the practice of animal sacrifice which was the essence of Brahmanism and to which Buddhism was deadly opposed.

That in an agricultural population there should be respect for Buddhism and revulsion against Brahmanism which involved slaughter of animals including cows and bullocks is only natural. What could the Brahmins do to recover the lost ground? To go one better than the Buddhist Bhikshus not only to give up meat-eating but to become vegetarians – which they did. That this was the object of the Brahmins in becoming vegetarians can be proved in various ways.

If the Brahmins had acted from conviction that animal sacrifice was bad, all that was necessary for them to do was to give up killing animals for sacrifice. It was unnecessary for them to be vegetarians. That they did go in for vegetarianism makes it obvious that their motive was far-reaching.

Secondly, it was unnecessary for them to become vegetarians. For the Buddhist Bhikshus were not vegetarians. This statement might surprise many people owing to the popular belief that the connection between Ahimsa and Buddhism was immediate and essential. It is generally believed that the Buddhist Bhikshus eschewed animal food. This is an error.

The fact is that the Buddhist Bhikshus were permitted to eat three kinds of flesh that were deemed pure. Later on they were extended to five classes. Yuan Chwang, the Chinese traveller was aware of this and spoke of the pure kinds of flesh as San-Ching...

As the Buddhist Bhikshus did eat meat the Brahmins had no reason to give it up. Why then did the Brahmins give up meat-eating and become vegetarians? It was because they did not want to put themselves merely on the same footing in the eyes of the public as the Buddhist Bhikshus.

The giving up of the Yajna system and abandonment of the sacrifice of the cow could have had only a limited effect. At the most it would have put the Brahmins on the same footing as the Buddhists. The same would have been the case if they had followed the rules observed by the Buddhist Bhikshus in the matter of meat-eating. It could not have given the Brahmins the means of achieving supremacy over the Buddhists which was their ambition.

They wanted to oust the Buddhists from the place of honour and respect which they had acquired in the minds of the masses by their opposition to the killing of the cow for sacrificial purposes. To achieve their purpose the Brahmins had to adopt the usual tactics of a reckless adventurer. It is to beat extremism with extremism. It is the strategy which all rightists use to overcome the leftists. The only way to beat the Buddhists was to go a step further and be vegetarians.

There is another reason which can be relied upon to support the thesis that the Brahmins started cow-worship, gave up beef-eating and became vegetarians in order to vanquish Buddhism. It is the date when cow-killing became a mortal sin. It is well-known that cow-killing was not made an offence by Asoka. Many people expect him to have come forward to prohibit the killing of the cow. Prof Vincent Smith regards it as surprising. But there is nothing surprising in it.

Buddhism was against animal sacrifice in general. It had no particular affection for the cow. Asoka had therefore no particular reason to make a law to save the cow. What is more astonishing is the fact that cow-killing was made a Mahapataka, a mortal sin or a capital offence by the Gupta Kings who were champions of Hinduism which recognised and sanctioned the killing of the cow for sacrificial purposes...

The question is why should a Hindu king have come forward to make a law against cow-killing, that is to say, against the Laws of Manu? The answer is that the Brahmins had to suspend or abrogate a requirement of their Vedic religion in order to overcome the supremacy of the Buddhist Bhikshus.

If the analysis is correct then it is obvious that the worship of the cow is the result of the struggle between Buddhism and Brahminism. It was a means adopted by the Brahmins to regain their lost position.

Why should beef-eating make broken men Untouchables?

THE stoppage of beef-eating by the Brahmins and the non-Brahmins and the continued use thereof by the Broken Men had produced a situation which was different from the old. This difference lay in the face that while in the old situation everybody ate beef, in the new -situation one section did not and another did.

The difference was a glaring difference. Everybody could see it. It divided society as nothing else did before. All the same, this difference need not have given rise to such extreme division of society as is marked by Untouchability. It could have remained a social difference. There are many cases where different sections of the community differ in their foods. What one likes the other dislikes and yet this difference does not create a bar between the two.

There must therefore be some special reason why in India the difference between the Settled Community and the Broken Men in the matter of beef eating created a bar between the two.

What can that be? The answer is that if beef-eating had remained a secular affair – a mere matter of individual taste – such a bar between those who ate beef and those who did not would not have arisen.

Unfortunately beef-eating, instead of being treated as a purely secular matter, was made a matter of religion. This happened because the Brahmins made the cow a sacred animal. This made beef-eating a sacrilege. The Broken Men being guilty of sacrilege necessarily became beyond the pale of society.

The answer may not be quite clear to those who have no idea of the scope and function of religion in the life of the society. They may ask: Why should religion make such a difference? It will be clear if the following points regarding the scope and function of religion are borne in mind.

To begin with the definition of religion. There is one universal feature which characterises all religions. This feature lies in religion being a unified system of beliefs and practices which (1) relate to sacred things and (2) which unite into one single community all those who adhere to them.

To put it slightly differently, there are two elements in every religion. One is that religion is inseparable from sacred things. The other is that religion is a collective thing inseparable from society.

The first element in religion presupposes a classification of all things, real and ideal, which are the subject-matter of man's thought, into two distinct classes which are generally designated by two distinct terms the sacred and the profane, popularly spoken of as secular.

This defines the scope of religion. For understanding the function of religion the following points regarding things sacred should be noted:

The first thing to note is that things sacred are not merely higher than or superior in dignity and status to those that are profane. They are just different. The sacred and the profane do not belong to the same class. There is a complete dichotomy between the two. As Prof Durkhiem observes:

“The traditional opposition of good and bad is nothing beside this; for the good and the bad are only two opposed species of the same class, namely, morals, just as sickness and health are two different aspects of the same order of facts, life, while the sacred and the profane have always and everywhere been conceived by the human mind as two distinct classes, as two worlds between which there is nothing in common.”The curious may want to know what has led men to see in this world this dichotomy between the sacred and the profane. We must however refuse to enter into this discussion as it is unnecessary for the immediate purpose we have in mind.

Confining ourselves to the issue the next thing to note is that the circle of sacred objects is not fixed. Its extent varies infinitely from religion to religion. Gods and spirits are not the only sacred things. A rock, a tree, an animal, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word anything can be sacred. Things sacred are always associated with interdictions otherwise called taboos. To quote Prof Durkhiem again:

“Sacred things are those which the interdictions protect and isolate; profane things, those to which these interdictions are applied and which must remain at a distance from the first.”Religious interdicts take multiple forms. Most important of these is the interdiction on contact. The interdiction on contact rests upon the principle that the profane should never touch the sacred.

Contact may be established in a variety of ways other than touch.

A look is a means of contact. That is why the sight of sacred things is forbidden to the profane in certain cases. For instance, women are not allowed to see certain things which are regarded as sacred.

The word (i.e., the breath which forms part of man and which spreads outside him) is another means of contact. That is why the profane is forbidden to address the sacred things or to utter them. For instance, the Veda must be uttered only by the Brahmin and not by the Shudra.

An exceptionally intimate contact is the one resulting from the absorption of food. Hence comes the interdiction against eating the sacred animals or vegetables.

The interdictions relating to the sacred are not open to discussion. They are beyond discussion and must be accepted without question. The sacred is "untouchable" in the sense that it is beyond the pale of debate. All that one can do is to respect and obey.

Lastly the interdictions relating to the sacred are binding on all. They are not maxims. They are injunctions. They are obligatory but not in the ordinary sense of the word. They partake of the nature of a categorical imperative. Their breach is more than a crime. It is a sacrilege.

The above summary should be enough for an understanding of the scope and function of religion. It is unnecessary to enlarge upon the subject further.

The analysis of the working of the laws of the sacred which is the core of religion should enable any one to see that my answer to the question why beef-eating should make the Broken Men untouchables is the correct one. All that is necessary to reach the answer I have proposed is to read the analysis of the working of the laws of the sacred with the cow as the sacred object.

It will be found that Untouchability is the result of the breach of the interdiction against the eating of the sacred animal, namely, the cow.

As has been said, the Brahmins made the cow a sacred animal. They did not stop to make a difference between a living cow and a dead cow. The cow was sacred, living or dead. Beef-eating was not merely a crime. If it was only a crime it would have involved nothing more than punishment. Beef-eating was made a sacrilege. Anyone who treated the cow as profane was guilty of sin and unfit for association. The Broken Men who continued to eat beef became guilty of sacrilege.

Once the cow became sacred and the Broken Men continued to eat beef, there was no other fate left for the Broken Men except to be treated unfit for association, i.e., as Untouchables.

Obvious objections

Before closing the subject it may be desirable to dispose of possible objections to the thesis. Two such objections to the thesis appear obvious.

One is what evidence is there that the Broken Men did eat the flesh of the dead cow. The second is why did they not give up beef-eating when the Brahmins and the non-Brahmins abandoned it.

These questions have an important bearing upon the theory of the origin of untouchability advanced in this book and must therefore be dealt with.

The first question is relevant as well as crucial. If the Broken Men were eating beef from the very beginning, then obviously the theory cannot stand. For, if they were eating beef from the very beginning and nonetheless were not treated as Untouchables, to say that the Broken Men became Untouchables because of beef-eating would be illogical if not senseless.

The second question is relevant, if not crucial. If the Brahmins gave up beef-eating and the non-Brahmins imitated them why did the Broken Men not do the same? If the law made the killing of the cow a capital sin because the cow became a sacred animal to the Brahmins and non-Brahmins, why were the Broken Men not stopped from eating beef? If they had been stopped from eating beef there would have been no Untouchability.

The answer to the first question is that even during the period when beef-eating was common to both, the Settled Tribesmen and the Broken Men, a system had grown up whereby the Settled Community ate fresh beef, while the Broken Men ate the flesh of the dead cow. We have no positive evidence to show that members of the Settled Community never ate the flesh of the dead cow. But we have negative evidence which shows that the dead cow had become an exclusive possession and perquisite of the Broken Men.

The evidence consists of facts which relate to the Mahars of the Maharashtra to whom reference has already been made. As has already been pointed out, the Mahars of the Maharashtra claim the right to take the dead animal. This right they claim against every Hindu in the village. This means that no Hindu can eat the flesh of his own animal when it dies. He has to surrender it to the Mahar. This is merely another way of stating that when eating beef was a common practice the Mahars ate dead beef and the Hindus ate fresh beef.

The only questions that arise are: Whether what is true of the present is true of the ancient past? Can this fact which is true of the Maharashtra be taken as typical of the arrangement between the Settled Tribes and the Broken Men throughout India?

In this connection reference may be made to the tradition current among the Mahars according to which they claim that they were given 52 rights against the Hindu villagers by the Muslim King of Bedar. Assuming that they were given by the King of Bedar, the King obviously did not create them for the first time. They must have been in existence from the ancient past. What the King did was merely to confirm them. This means that the practice of the Broken Men eating dead meat and the Settled Tribes eating fresh meat must have grown in the ancient past.

That such an arrangement should grow up is certainly most natural. The Settled Community was a wealthy community with agriculture and cattle as means of livelihood. The Broken Men were a community of paupers with no means of livelihood and entirely dependent upon the Settled Community. The principal item of food for both was beef. It was possible for the Settled Community to kill an animal for food because it was possessed of cattle. The Broken Men could not for they had none.

Would it be unnatural in these circumstances for the Settled Community to have agreed to give to the Broken Men its dead animals as part of their wages of watch and ward? Surely not. It can therefore be taken for granted that in the ancient past when both the Settled Community and Broken Men did eat beef the former ate fresh beef and the latter of the dead cow and that this system represented a universal state of affairs throughout India and was not confined to the Maharashtra alone.

This disposes of the first objection. To turn to the second objection. The law made by the Gupta Emperors was intended to prevent those who killed cows. It did not apply to the Broken Men. For they did not kill the cow. They only ate the dead cow. Their conduct did not contravene the law against cow-killing. The practice of eating the flesh of the dead cow therefore was allowed to continue.

Nor did their conduct contravene the doctrine of Ahimsa assuming that it has anything to do with the abandonment of beef-eating by the Brahmins and the non-Brahmins. Killing the cow was Himsa. But eating the dead cow was not. The Broken Men had therefore no cause for feeling qualms of conscience in continuing to eat the dead cow. Neither the law nor the doctrine of Himsa could interdict what they were doing, for what they were doing was neither contrary to law nor to the doctrine.

As to why they did not imitate the Brahmins and the non-Brahmins the answer is two fold. In the first place, imitation was too costly. They could not afford it. The flesh of the dead cow was their principal sustenance. Without it they would starve.

In the second place, carrying the dead cow had become an obligation though originally it was a privilege. As they could not escape carrying the dead cow they did not mind using the flesh as food in the manner in which they were doing previously.

Excerpted from Chapters 9 to 14 (Part IV and V) of B.R. Ambedkar’s 1948 work The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables? as reprinted in Volume 7 of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches.

It is the responsibility of non-Dalit journalists to be casteless and fight for equality in the country.

15/NOV/2016

Students in Delhi protest against the death of Rohith Vemula. Credit: PTI

This is the English translation of a speech given by Jeya Rani, a journalist for over 15 years from Tamil Nadu at the Network of Women in Media in India (NWMI) conference last week. NWMI is an informal collective of women journalists across the country.

Jeya spoke of her experiences as a Dalit woman journalist and the caste, class, gender bias in mainstream media. The speech was given in Tamil and has been translated by Kavitha Muralidharan.

As responsible journalists and people with creative instincts, let us imagine an interesting scenario. What if tomorrow a law is enacted insisting that all the media houses in the country should prioritise and publish/telecast only caste related atrocities. Let us remember this is just a wild imagination. What would happen then? What if there is an emergency like situation? What if a media house is threatened with the cancellation of license if it fails to adhere to the law? Again, this is just an imagination. We all know what would happen. The media houses will be forced to expose a caste atrocity every second. They will have to expose caste related violence every minute. But they would not be daunted by the task.

Jeya Rani. Courtesy: Neha Dixit

Even as I stand here speaking to you, somewhere someone is being killed or raped, humiliated or outraged, just because she or he was born in a lower caste.

The ‘not so changing’ statistics of National Crime Records Bureau say that a Dalit is assaulted every two hours in India. So we would get breaking news every two hours.

At least three Dalit women are raped every 24 hours. Call it exclusive, mask the face of the woman or you can even leave it unmasked since she is a Dalit and keep breaking the news.

Two Dalits are killed every 24 hours. Two Dalit houses are burnt down. There would be no dearth of breaking news or good TRP ratings. In an era where violence incites more sensationalism than a porn video, commercialising Dalit atrocities will only be beneficial. As long as the six lakh villages in India are segregated as oors (where the dominant castes live) and cheris (where the Dalits live), as long as the hands of dominant castes write and enforce the living laws for Dalits through khappanchayats, there would be no scarcity of news related to violence against Dalits.

If there were such a law, as we are now imagining, breaking news would become the norm of the day. Like channels created war rooms to encourage the war against Pakistan, there would be caste clash rooms, violence rooms, untouchability rooms, protection of cow rooms and ghar wapsi rooms.

I wish this would happen for us to really understand how bad the caste domination is in India today. To many of us, caste atrocities are just what we hear or see. We never get a complete idea about what really happens in terms of caste atrocities throughout the country. It is like blind people touching the elephant. I believe the country’s indifference to the caste atrocities largely arises from this blind men and the elephant idea.

Now let’s go back to the real world.

So now we know the violence against the Dalits are like Akshaya Patra to the news hungry media. The thousands of print media houses and hundreds of television houses will always have something new to give its readers and viewers. But how does the media actually see the atrocities against Dalits? What is the space, in terms of percentage, given to violence on Dalits in a day, a week, a month and a year by the media houses?

Crimes against Dalits see a rise of 10-20% every year. In a just society, the media’s space to violence against Dalits should have correspondingly increased too. But has it happened? We all know it has not. Now let us understand why it has not happened.

Just like in a society where we have rigid caste hierarchies, the media and journalists too operate on the basis of caste hierarchies. The fourth pillar of democracy has come crumbling down under the pressure of caste hierarchies when it should have stood upright holding the torch of justice.

There is a term called oozhikaalam in Tamil. The closest English word to it is apocalypse. As a responsible journalist, I would call this era the apocalypse of the media world. Because, it is precisely this media world that controls the entire movement of society. The media decides what should happen today, what I should be discussing today, how I should think on an issue, what decision to take, what to eat or what to buy. The media’s influence on individual decisions is largely conditioned by the one-dimensional approach of the powers-to-be. What media sows in the morning is harvested by society in the evening. What media writes every day becomes the judgment on anything and everything in the following days.

The mainstream media is not for the poor, not for the oppressed. It has carved its kingdom out of loyalty to the powers, to bureaucracy, to domination. It is neither for minorities nor for women and children. Most certainly not for the Dalits. Over 95% of owners of the mainstream media including print and television come from dominant caste backgrounds. About 70-80% of the topmost positions are occupied by dominant caste men. Dalits don’t even constitute 1% when it comes to deciding power in the country’s media. When the diversity of media is butchered, how can Dalits and the oppressed expect any justice or even space from them?

English media, once in a while, does carry news on caste atrocities. But the possibility of even carrying anything remotely connected to violence on Dalits is ruled out completely in the vernacular media. Dalit journalists invariably end up in the vernacular media due to various factors. That includes their family and societal factors. Most Dalit journalists are first generation graduates. They lack the ‘desired colour’ and they lack proficiency in English. Vernacular media accommodates them but treats them badly. They are not considered on par with journalists from other communities when it is time for promotions or salary hikes. And this I also say from my own experience.

After ten years of media experience, the channel I worked for paid me a meagre Rs 18,000. I was a scriptwriter for a daily show, worked through days and nights and had earned respect for my work. But when it was time for salary hike, I did not even get a 100 rupee raise. A junior employee, with less work load, but obviously from a different caste, was given a greater hike. Her salary was Rs 40,000. This is what Dalits face in media. They have only two options: to shrink themselves to fit the space media offers them or to leave the profession altogether.

The story had appeared in my university magazine and after that, I almost faced suspension. That was my first story and the experience fuelled my passion to write more against caste related atrocities. But when I transitioned to mainstream media looking for employment opportunities, I was in for a rude shock. There were two things that acted as speed breakers. For a vernacular journalist to go about working on socio-political stories was considered unwanted. Unless there is a mass murder, violence against Dalits was never taken into account. All my ideas for stories were trashed. I was seen as something of a rebel.

As soon as I began my career, in a matter of few months I ended up as a reporter for a women’s magazine. I suggested a serial on women panchayat presidents. The idea was trashed several times as not being fit for a women’s magazine, but I kept persisting. Finally when it was accepted I made a list of five leaders I could meet and set up my first meeting with Menaka.

She was then a panchayat president with Oorapakkam panchayat in Kanchipuram district. I had no idea that she was a Dalit.

I had wanted to speak of the challenges she faced as a woman. Menaka was speaking about the challenges she faced as a Dalit. She told me the members of dominant caste never allowed her to sit in the chair meant for the panchayat president. She was receiving death threats. They wanted her to quit her post. She had filed a complaint against police station, but there was no action on her complaint.

After spending a day with her and gathering her experiences, I went back to the office next day and filed my story. It was trashed again. It was apparently not suitable for the magazine. My editor insisted I write recipes instead. I distinctly remember the evening. Under huge mental pressure I was walking on the road contemplating if I should quit the job that wanted me to write only recipes. Something in the posters of the evening newspapers caught my eye. The posters screamed about the murder of a panchayat president and I was trembling when I bought the paper. My worst fears had come true. Menaka was murdered for sitting on the chair in the panchayat office.