Dalit Sahirs

Arjun Hari Bhalerao

Full name: Arjun Hari Jagtap (stage name: Shahir Arjun Hari Bhalerao) Born: 1 December 1932, Bhalerao Wadi (near Shrirampur), Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra Died: 27 November 2004, Pune Community: Mahar (Scheduled Caste / Dalit) Occupation: Shahir (folk poet-singer), Powada and Lavani performer, social activist, playwright

Early Life – From Village Boy to Voice of Resistance

Born into a landless Mahar family in rural Ahmednagar, Arjun grew up witnessing extreme caste oppression and poverty. His father Hari was a farm labourer; the family lived in the traditional Maharwada (Dalit settlement) outside the village. Like most Mahar children of the 1930s–40s, he faced untouchability daily: barred from village wells, temples, and schools.

He studied only up to Class 4 because the school refused to let Mahar children sit inside the classroom. Instead, they were made to sit outside on the veranda. Yet, even in childhood, Arjun showed extraordinary talent for singing, storytelling, and mimicry. Village elders recall that by age 10–12 he could already compose and sing short Powadas about local events.

The turning point came when he attended Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s historic speech in Ahmednagar in the 1940s. The message of self-respect and fight against caste lit a fire in the young boy. He later said: “Babasaheb gave me my real education on the stage of life.”

Rise as a Shahir (1948–1970)

- Started performing at small village jalsas (folk gatherings) in the late 1940s.

- Took the stage name “Bhalerao” after his native hamlet.

- Initially accompanied senior Shahirs such as Vitthal Umap and Shahir Sable, learning the traditional Powada style.

- By the mid-1950s, his booming, thunder-like voice and fearless anti-caste lyrics made him famous across Marathwada and western Maharashtra.

- Performed with the legendary jalsa troupe “Ambedkari Shahiri Jalsa Mandal” and later formed his own troupe.

Style & Signature Themes

Arjun Hari Bhalerao revolutionized Shahiri by bringing Dalit consciousness to the centre of folk performance:

- Voice: Deep, resonant, almost earthquake-like — people said “when Bhalerao sings, even the ground shakes.”

- Main forms: Powada (heroic ballad), Lavani (satirical or emotional), Ambedkari Jalsa songs, Bhim-geete.

- Recurring themes:

- Brutal reality of untouchability and caste atrocities

- Dr. Ambedkar’s life and message

- Call for education and self-respect among Dalits

- Critique of Brahminical hegemony and village landlords

- Unity of Bahujan Samaj (SC/ST/OBC)

Some of his most famous Powadas:

- “Maharancha Navha Konacha” (A Mahar belongs to no one but himself)

- “Bhimraya Tumhi Amhi Sagale” (We are all your children, Bhimraya)

- “Gav Ranganarya Porancha” (The wild boys of the village)

- “Dalit Panther chi Powada” (written after the rise of Dalit Panthers in 1972)

Major Achievements & Recognition

- Performed more than 15,000 stage shows across Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Goa.

- First Dalit Shahir to be invited to perform at prestigious urban venues (Fergusson College, Pune; Mumbai’s Shivaji Mandir, etc.).

- Awarded the Maharashtra State Government’s “Best Shahir” award multiple times.

- Received the Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Dalit Sahitya Academy Award.

- In 1998, the Government of Maharashtra honoured him with the Sant Tukaram Award.

- Posthumously awarded the Shahir Amar Shaikh Puraskar and several Dalit literary honours.

Personal Life

- Married Lakshmibai; had three sons and two daughters.

- Lived a simple life in Pune’s Yerawada area, close to the Dalit basti.

- Remained politically independent but always supported Ambedkarite ideology; never joined any political party.

- Mentored younger Dalit artists including Sambhaji Bhagat, Prakash Jadhav, and many local Shahirs.

Last Years & Death

Even in his 70s, he continued performing until illness slowed him down. On 27 November 2004, he passed away in Pune after a prolonged illness. Thousands of people from villages and cities attended his funeral; his bier was carried like a revolutionary leader’s.

Legacy

Arjun Hari Bhalerao is today regarded as the most powerful Dalit voice in 20th-century Maharashtrian folk tradition. Along with Shahir Sable, Vitthal Umap, and Annabhau Sathe, he transformed Shahiri from a caste-neutral entertainment form into a weapon of social revolution.

His recordings are still played at Ambedkar Jayanti celebrations, Dalit rallies, and village jalsas. Young Dalit activists and artists call him “Dalit Shahirancha Raja” (The King of Dalit Shahirs).

Caste summary: Mahar (Scheduled Caste) – proudly claimed and celebrated throughout his life and work.

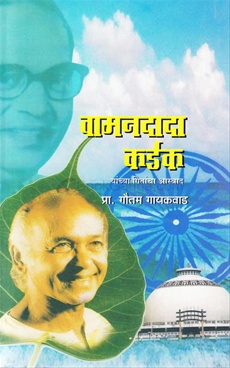

Bhimrao Kardak

Bhimrao Kardak (1904–1978), fondly known as Shahir Bhimrao Kardak, was a pioneering Dalit folk poet-singer, playwright, and social activist from Maharashtra, celebrated as the founder of the "Ambedkari Jalsa" tradition—a powerful musical and theatrical form that spread B.R. Ambedkar’s anti-caste philosophy among the masses. Born into the Matang (Mang) Scheduled Caste (SC) community, Kardak transformed traditional Marathi folk arts like tamasha and powada into tools of Dalit empowerment, challenging Brahminical hegemony and caste oppression. His performances, marked by biting satire, soulful melodies, and accessible lyrics, made Ambedkar’s complex ideas resonate with illiterate rural audiences, earning him the title “Voice of the Voiceless.” From his first troupe in 1928 to his death in 1978, Kardak’s life was a testament to art as resistance, bridging cultural expression with social revolution. On November 11, 2025, his legacy endures in Maharashtra’s vibrant Dalit cultural movements, inspiring new generations of shahirs and activists.

Early Life and Background

Born in Kasabe Kunabe village, Sinnar taluka, Nashik district, Maharashtra, Bhimrao Kardak grew up in a marginalized Matang family, a Dalit caste traditionally linked to rope-making, drumming, and tamasha performances. The Matangs, classified as Scheduled Castes, faced severe untouchability, economic exclusion, and social stigma, which profoundly shaped Kardak’s worldview. Orphaned young, he was raised in poverty, with minimal access to formal education—completing only primary schooling. Yet, his innate talent for poetry and music, nurtured in the vibrant tamasha culture of rural Maharashtra, set him apart.

- Cultural Roots: The Matang community’s association with folk arts gave Kardak early exposure to lavani (erotic folk songs), powada (heroic ballads), and tamasha (traveling theater). However, tamasha often exploited Dalit women performers, a reality Kardak later sought to reform through his anti-caste lens.

- Early Influences: Inspired by the 19th-century shahir Patthe Bapurao, a Matang pioneer who elevated tamasha’s literary quality, Kardak began composing songs as a teenager. The rise of Ambedkar’s Dalit movement in the 1920s, particularly the Mahad Satyagraha (1927), galvanized his resolve to use art for social change.

Emergence as a Shahir and Ambedkarite Activist

Kardak’s career as a shahir (folk poet-singer) began in the 1920s, but his defining moment came in 1928 when he founded his tamasha troupe in Nashik. By the early 1930s, he aligned with Ambedkar’s movement, transforming his performances into “Ambedkari Jalsa”—a new genre blending music, drama, and political messaging to advocate Dalit rights and annihilation of caste. Unlike traditional tamasha, which often pandered to feudal audiences, jalsa was revolutionary, performed at Dalit rallies, Buddhist conversion events, and Ambedkar’s public meetings.

- First Major Performance: In 1937, at the Kasarwadi meeting in Bombay, Kardak’s troupe performed before Ambedkar, who praised its impact, saying, “Ten of my meetings are equal to one jalsa by Kardak and his troupe.” This endorsement cemented his role as a cultural ambassador for the Ambedkarite movement.

- Artistic Innovations:

- Songs and Powadas: Kardak composed hundreds of songs, including Bheem Geete (songs glorifying Ambedkar) and powadas narrating Dalit struggles, such as the Mahad Satyagraha or Poona Pact (1932). His lyrics, in simple Marathi, made Ambedkar’s legal and philosophical arguments accessible to farmers and laborers.

- Farces and Plays: He wrote satirical farces exposing caste hypocrisy, often portraying Brahmin priests or landlords as villains. His plays, performed by mixed-caste troupes, challenged untouchability norms.

- Reforming Tamasha: Kardak purged tamasha of its misogynistic elements, empowering Dalit women performers like his sister-in-law Godavaribai to take lead roles with dignity.

- Collaboration with Ambedkar: Kardak performed at key Ambedkarite events, including the 1956 mass Buddhist conversion in Nagpur, where his songs celebrated Dalit embrace of Buddhism as liberation from Hindu casteism. His troupe’s mobility—traveling across Maharashtra’s villages—amplified Ambedkar’s call for education, agitation, and organization.

Key Contributions to Dalit Cultural and Political Movements

Kardak’s work bridged art and activism, creating a cultural renaissance for Maharashtra’s Dalits. His contributions include:

| Contribution | Details | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Ambedkari Jalsa | Founded in the 1930s; combined music, theater, and anti-caste propaganda. | Reached illiterate masses, making Ambedkar’s ideas a household narrative; inspired other shahirs like Vaman Kardak and Annabhau Sathe. |

| Literary Output | Authored nine books, including Ambedkari Jalse: Swarup Aani Karya (1978), documenting jalsa’s history and techniques. | Preserved Dalit oral traditions in print; provided a blueprint for future performers. |

| Women’s Empowerment | Promoted Dalit women like Godavaribai and Susheela Deole in his troupe, defying tamasha’s exploitative norms. | Elevated women’s agency in Dalit arts, challenging caste-gender intersections. |

| Buddhist Revival | Composed songs for the 1956 Buddhist conversion, linking Dalit identity to Navayana Buddhism. | Strengthened Dalit-Buddhist identity, with songs still sung at Deekshabhoomi events. |

| Political Mobilization | Performed at rallies for the Scheduled Castes Federation and Republican Party of India (RPI), boosting Dalit political consciousness. | Galvanized votes for Ambedkarite parties, especially in 1950s–60s Maharashtra. Notable Works: |

- Bheem Vijay Geet: Songs glorifying Ambedkar’s victories, like the 1930 Kalaram Temple entry movement.

- Chavdar Tale Satyagraha: A powada narrating the Mahad water rights struggle.

- Castecha Band Fodun Taka: A satirical farce urging Dalits to break caste barriers.

His performances, often free or funded by Dalit communities, were staged in open fields or chawls, making them accessible to the poorest. By 1970, his troupe had performed over 10,000 shows, covering Maharashtra, Gujarat, and parts of Karnataka.

Challenges and Resilience

Kardak faced significant hurdles due to his caste and radical message:

- Caste Discrimination: Upper-caste audiences and theater owners boycotted his shows, labeling them “polluting.” He was often denied stage access in urban venues, forcing reliance on rural Dalit bastis.

- Economic Struggles: With no institutional support, Kardak funded his troupe through personal savings and donations, living frugally. His family, including wife and children, endured poverty to sustain his mission.

- Political Backlash: His critiques of Hindu orthodoxy and Congress’s casteism drew threats from conservative groups. During the 1940s, he faced arrests for “seditious” performances under colonial laws.

- Cultural Erasure: Mainstream Marathi literary circles, dominated by Brahmins, marginalized his contributions, dismissing jalsa as “low art” compared to classical forms.

Despite these, Kardak’s charisma and wit won him allies across castes, including progressive Marathi writers like P.L. Deshpande, who admired his lyrical depth. His mentorship of shahirs like his nephew Wamandada Kardak (1922–2008), who composed 10,000+ songs, ensured the jalsa tradition’s continuity.

Legacy and Modern Commemoration

Bhimrao Kardak’s death in 1978 marked the end of an era, but his influence endures in Maharashtra’s Dalit cultural and political spheres:

- Cultural Impact: The Ambedkari Jalsa remains a vibrant tradition, performed at Dalit History Month (April) and Ambedkar Jayanti (April 14). Modern shahirs like Sambhaji Bhagat and groups like Kabir Kala Manch draw directly from Kardak’s playbook, blending folk with hip-hop and protest rap.

- Institutional Recognition:

- The Maharashtra government’s Shahir Bhimrao Kardak Award honors folk artists advancing social justice.

- Universities like Savitribai Phule Pune University include his works in Marathi literature syllabi, with Ph.D. theses analyzing his contributions (e.g., Ambedkari Jalsacha Samajik Prabodhan).

- Community Tributes: In Nashik and Pune, Dalit-Buddhist groups maintain Kardak’s memory through statues, libraries, and annual jalsa festivals. On November 11, 2025, social media posts and local events in Sinnar commemorate his birth anniversary, though no statewide programs are reported.

- Media and Revival: Documentaries on YouTube (e.g., by Ambedkarite channels) and articles in The Mooknayak spotlight his role. His songs, archived by organizations like the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), are digitized for global access.

- Family Legacy: Wamandada Kardak, his nephew, and other Matang shahirs like Viththal Umap carried forward his vision. Wamandada’s song “Bhimacha Danka Wajato” remains an anthem at Dalit rallies.

- Contemporary Relevance: In 2025, amid rising caste violence and debates over reservations in Maharashtra, Kardak’s songs—urging education and unity—resonate at protests like those following the 2023 Parbhani clashes. His critique of “Manusmriti mentality” aligns with VCK and RPI campaigns against Hindutva’s casteist undertones.

Personal Life and Character

Kardak married early, raising a family in Nashik despite financial strain. His wife (name undocumented) supported his travels, often managing the household alone. Known for his humility, he wore simple khadi dhotis and lived in a modest home, reinvesting earnings into his troupe. A devout Buddhist post-1956, he incorporated Navayana principles into his art, rejecting Hindu rituals. His humor—evident in farces mocking casteist priests—endeared him to audiences, while his fiery speeches rallied Dalit youth.

Sources for Further Reading

- Primary Works: Kardak’s Ambedkari Jalse: Swarup Aani Karya (1978, Marathi) offers insights into his methods.

- Scholarly Studies: Anand Patil’s Dalit Literature and Aesthetics and Sharmila Rege’s Writing Caste/Writing Gender analyze his contributions.

- Biographical Accounts: The Mooknayak and Round Table India articles (2020–2023) detail his life.

- Oral Histories: Interviews with Wamandada Kardak (archived by Lokshahir Viththal Umap Smarak Samiti) provide personal anecdotes.

Krishnarao Ganpatrao Sable

Krishnarao Ganpatrao Sable, popularly known as Shahir Sable (3 September 1923 – 20 March 2015), was a legendary Marathi folk artist, singer, playwright, performer, and folk theatre (Loknatya) producer and director from Maharashtra, India. His contributions to Marathi culture, Indian independence movements, and social reform through folk art are monumental. Below is a comprehensive account of his life, work, and legacy based on available information.

Early Life

- Birth and Family: Born on 3 September 1923 in Pasarni, a small village in the Wai taluka of Satara district, Maharashtra, to Ganpatrao Sable. His mother sang traditional ovi (folk songs) while grinding grain, and his father, a Warkari, performed devotional bhajans, which influenced his early exposure to music.

- Childhood and Education: Krishnarao learned to play the flute during his childhood. He completed primary schooling in Pasarni and later moved to his maternal uncle’s home in Amalner, Jalgaon, where he studied until the 7th grade. He left school early to pursue his passion for music and social causes.

- Influence of Sane Guruji: In Amalner, he met the revered Gandhian writer and freedom fighter Sane Guruji, whose philosophy deeply influenced him. This connection sparked his involvement in India’s freedom struggle and social reform movements.

Career and Contributions

Shahir Sable was a multifaceted artist whose work spanned music, theatre, and social activism. His contributions can be categorized as follows:

1. Folk Art and Music

- Shahir Tradition: As a Shahir (folk poet-singer), Sable used powadas (ballads) and lavani (folk songs) to narrate stories of valor, social issues, and cultural pride. His performances were known for their emotional depth and ability to connect with the masses.

- Iconic Songs: His most famous song, "Jai Jai Maharashtra Majha", became an anthem of Marathi pride and was declared the official state song of Maharashtra in 2023. Other notable compositions include Are Krishna Are Kanha, Malharavaari, and Vinchhu Chavla (a popular bharud). Many of his songs, often written by his first wife Bhanumati Sable, were later adapted for Marathi films.

- Maharashtrachi Lokadhara: Sable founded the renowned troupe Maharashtrachi Lokadhara, which performed across India, reviving traditional Maharashtrian folk dance forms like Lavani, Balyanruttya, Kolinruttya, Gondhalinruttya, Manglagaur, Vaghyamurali, Vasudeo, and Dhangar. This troupe was later adapted into a TV show by his grandson Kedar Shinde, aired on Zee Marathi.

- Musical Collaborations: He collaborated with his son, Devdatta Sable, a noted Marathi music composer, on compositions like Aathshe Khidkya Naushe Dare. His work blended traditional folk with contemporary themes, making it accessible to diverse audiences.

2. Folk Theatre (Loknatya)

- Innovator of Mukta Natya: Sable transformed the traditional Loknatya (folk theatre) by introducing Mukta Natya (free drama), a more accessible and socially relevant form of theatre.

- Andhala Daltay: His farcical play Andhala Daltay highlighted the struggles of Marathi-speaking residents in Mumbai. It is widely believed to have inspired the formation of the Shiv Sena, a political party advocating for the rights of native Marathi people.

- Social Messaging: His plays and performances addressed social evils like alcohol abuse, illiteracy, and caste discrimination, while promoting regional pride and unity.

3. Social and Political Activism

- Freedom Struggle: Sable actively participated in India’s independence movement, including the 1942 Quit India Movement, Hyderabad Liberation Struggle, and Goa Mukti Andolan. His powadas stirred nationalist sentiments and mobilized public support.

- Samyukta Maharashtra Movement: During the movement for a unified Maharashtra, his folk songs and performances played a crucial role in uniting Marathi-speaking people.

- Social Reforms: Inspired by Sane Guruji, Sable supported causes like temple entry for Dalits. He organized the Bhairavnath Temple entry in Pasarni, attended by notable figures like Senapati Bapat and Krantisinha Nana Patil. His inter-caste marriage to Bhanumati Barasode in 1948 was a bold statement against caste discrimination.

- Shahir Sable Pratishthan: In 1989, he founded the Shahir Sable Pratishthan and donated 8 acres of ancestral land near Pasarni to establish Tapasyashram, a shelter for aging and underprivileged folk artists to live with dignity and train younger generations.

4. Awards and Recognition

- Padma Shri (1998): Sable was honored with India’s fourth-highest civilian award for his contributions to the arts.

- Best Singer Award (2001): Conferred by the Maharashtra State Government.

- Cultural Legacy: His songs, such as Jai Jai Maharashtra Majha, are played at official Maharashtra government functions, and his work continues to inspire artists and activists.

Personal Life

- Marriages: Sable married twice. His first wife, Bhanumati Sable, was a poet who wrote many of his famous songs. Their inter-caste marriage was a significant step toward social reform. His second wife was Radhabai Sable.

- Family:

- Son: Devdatta Sable, a Marathi music composer.

- Daughter: Charushila Sable-Vachchani, an acclaimed dancer and actress.

- Son-in-law: Ajit Vachani, a noted Indian film and television actor.

- Grandsons: Shivadarshan Sable (film director and producer) and Kedar Shinde (noted Marathi film and theatre director).

- Great-granddaughter: Sana Kedar Shinde, who played Bhanumati Sable in the biopic Maharashtra Shahir.

Later Life and Death

- Health: Sable battled Alzheimer’s disease in his later years.

- Death: He passed away on 20 March 2015 at his residence in Mumbai at the age of 91.

- Legacy: His songs, plays, and cultural contributions continue to resonate in Maharashtra. His recordings are played at state events, and his message of social reform and cultural pride is taught to students.

Biopic: Maharashtra Shahir

- Release: A biographical film, Maharashtra Shahir, was released on 28 April 2023, directed by his grandson Kedar Shinde. It chronicles Sable’s life from the 1920s to the 1980s, with Ankush Chaudhari portraying Shahir Sable and Sana Kedar Shinde as Bhanumati Sable.

- Production: The film was produced by Sanjay Chhabria and Bela Shinde, with a screenplay by Pratima Kulkarni and Omkar Mangesh Datt. It featured music by Ajay-Atul, including reprised versions of Sable’s original songs and new compositions.

- Reception: The film received positive reviews, earning 3 to 3.5 stars from critics for its music, storytelling, and depiction of Sable’s legacy. It grossed over ₹5.68 crore at the box office, making it the fifth highest-grossing Marathi film of 2023. It was released on Amazon Prime Video on 2 June 2023.

- Controversy: A dialogue in the film’s trailer, “Aamhi kalaakar aahot pan kunache mindhe naahit” (We are artists, not helpless stooges), was linked by netizens to a political clash between Uddhav Thackeray and Eknath Shinde, causing minor controversy.

Cultural Impact

- Revival of Folk Traditions: Sable’s work preserved and popularized Maharashtra’s folk heritage, ensuring that traditional art forms like Lavani and Powada remained relevant.

- Social Awakening: His art was a powerful tool for social and political awakening, addressing issues like caste discrimination, regional identity, and social justice.

- Influence on Modern Media: His songs and theatre productions have been adapted by contemporary artists and filmmakers, and his legacy continues through his family’s contributions to Marathi cinema and theatre.

Vitthal Umap

Shahir Vitthal Umap (full name: Vitthal Gangaram Umap), fondly known as Loksahir Vitthal Umap, was one of India's most revered folk singers, poets, shahirs (traditional ballad singers), composers, actors, and social activists from Maharashtra. Born into a Dalit family during the era of intense social reform, he dedicated nearly seven decades of his life to preserving and revitalizing Maharashtra's folk traditions while using his art as a powerful tool for Ambedkarite activism, anti-caste advocacy, and social mobilization. His "Pahadi Awaaz" (mountainous voice)—raw, resonant, and enchanting—brought the struggles and joys of marginalized communities to life through songs, verse dramas, and performances. Umap's work not only enriched Marathi literature and music but also bridged folk art with mainstream cinema and global stages, earning him acclaim as a guardian of Dalit shahiri (anti-caste balladry). He passed away on stage in 2010, embodying his own poetic wish: "I should die while singing; and death should also listen to my songs."

Early Life and Background

Vitthal Umap was born on July 15, 1931, in a modest chawl (tenement) in Naigaon, central Mumbai (then Bombay), into a Dalit family during the British Raj. Growing up in poverty amid the bustling urban underbelly, he was profoundly influenced by the contemporary social upheavals led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of India's Constitution and a champion of Dalit rights. Ambedkar's mass conversions to Buddhism and anti-caste campaigns were unfolding in real-time during Umap's childhood, igniting his passion for social justice.

Umap discovered his vocal talent early, beginning to sing at just eight years old. He openly performed and spoke about Ambedkar's ideals even as a child, using simple folk tunes to spread messages of equality. By age 19, he was performing on stage, and in 1960, he recorded his first commercial song—a Koli (fisherfolk) folk track—for HMV (now Saregama), marking his entry into professional music. Despite financial hardships, he lived his entire life in a small single-room home in Vikhroli, Mumbai, where he raised his family and mentored young artists. He struggled for basic recognition, repeatedly petitioning the government for housing under the artistes' quota; he finally received it just months before his death, highlighting the systemic neglect faced by folk artists from marginalized backgrounds.

Family and Personal Life

Umap was a devoted family man, married with children whom he actively involved in music. His two sons, Sandesh Umap and Nandesh Umap, carried forward his legacy as singers and composers in the Marathi and Hindi film industries. Nandesh, in particular, has composed for films like Gaarud (2024), Fatwa (2022), and Shivbhakt: Pravas Eka Mavlyacha (2021), crediting his father's dedication to Indian folk traditions as his inspiration. Umap's home doubled as a music school, where he taught his children and neighborhood kids the nuances of folk forms, emphasizing sacrifice and cultural preservation. A practicing Buddhist and staunch Ambedkarite, he instilled values of equality and resilience in his family, often performing at home gatherings to keep traditions alive.

Career as a Shahir and Folk Artist

Umap's career spanned over 70 years, transforming him from a street performer to an international ambassador of Maharashtra's folk heritage. As a shahir, he specialized in shahiri—a narrative ballad form rooted in Sufi and Bhakti traditions but repurposed by Dalit artists for anti-caste critique. He revived nearly forgotten genres like Gavlan (milkmaid songs), Jambhool Akhyan (epic narratives), Khandobacha Lagin (wedding songs for deity Khandoba), and Gadhwacha Lagna (donkey wedding folk tales), performing them across Maharashtra to educate and entertain rural and urban audiences.

He composed over 1,000 folk songs, blending poetry, music, and storytelling to address caste oppression, gender inequality, and social reform. Umap traveled tirelessly, staging Padnatya (verse dramas) that dramatized Ambedkar's life and philosophy, making complex ideas accessible to the masses. His live performances, often impromptu and energetic, were legendary; recordings are widely available on platforms like YouTube, JioSaavn, and Gaana, showcasing his versatility in solo renditions and group ensembles.

In 1989, he was honored as "Maharashtra Shahir" at the Apna Utsav festival in the presence of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Cultural Minister Prabha Rau, where he performed and cut the ribbon as chief guest. Globally, he shone at the International Folk Music and Art Festival in Cork, Ireland, winning first prize for his authentic portrayal of Indian folk forms.

Notable Works: Songs, Compositions, Films, and Writings

Umap's oeuvre is vast, fusing activism with artistry. His song-books Mazi Vani Bhimacharani ("My Voice is Ambedkarite") and Mazi Aai Bhimai ("My Mother is Bhimai," referring to Ambedkar's mother) poetically unpacked Ambedkar's teachings on equality, Buddhism, and resistance to Brahmanical patriarchy. These works, written in simple Marathi, became anthems in Dalit-Buddhist communities.

Key Songs and Performances:

- "Bhimayichya Lekrane, Ramajichya Wasarane" (from Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar film): A stirring tribute to Ambedkar's legacy, blending folk rhythms with revolutionary fervor.

- "Bobali Gavlan" (Stammering Milkmaid): A subversive take on the traditional Gavlan form, critiquing the exploitation of women (like milkmaids in Krishna lore) under upper-caste landlords, transforming a celebratory genre into a protest against gender and caste violence.

- "Jay Jay Chatrapati Bola," "Aaj Kolivaryat Yeil Varat," "Jine Buddh Chharani Kaya Vahil," and "Kolyana Postoy Saminder": Bhim-Geete (Ambedkar songs) and folk hits that rally against untouchability.

- Non-stop medleys like Non Stop Superhit Bhim Buddha Geete (remixed versions popular today).

He composed music for numerous Marathi films, TV serials, and plays, infusing them with folk authenticity. Notable acting roles include:

- Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar (2000, dir. Jabbar Patel): Portrayed a key figure, earning widespread praise.

- Tingya (2008): Nominated for Best Actor at Maharashtra State Film Awards for his heartfelt role as a grandfather.

- Vihir (2009) and Bharat Ek Khoj (TV series, dir. Shyam Benegal): Supporting roles that highlighted his dramatic depth.

- Other films: Janmathep, Anyayacha Pratikar, Sumbaran.

His compositions appear in over 10 Marathi movies, and he lent his voice to devotional and social tracks, collaborating with artists like Pralhad Shinde and Anand Shinde.

Activism and Social Contributions

Umap was more than an entertainer—he was a social reformer. As an Ambedkarite Buddhist, he used shahiri to "resurrect Dalit identity in history," as noted by scholar Mahendra Gaikwad in Dalit Shahiri. His performances at Dikshabhoomi (Nagpur, site of Ambedkar's 1956 mass conversion) and other Buddhist events mobilized communities against caste atrocities. He advocated for the recognition of Dalit women’s oppression, land rights, and economic justice, often performing at protests and literacy drives.

Umap fought to keep folk arts alive amid Bollywood's dominance, training young Dalit artists and refusing to dilute his anti-caste themes for commercial gain. His work aligned with broader Dalit feminist and anti-caste movements, echoing figures like those in the National Federation of Dalit Women by amplifying marginalized voices through music.

Awards and Recognition

- Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (2009): India's highest honor for performing arts, awarded in 2010 for his contributions to folk music and shahiri.

- First Prize, International Folk Music and Art Festival, Cork, Ireland (date unspecified, likely 1980s–90s): For exemplary representation of Indian folk traditions.

- "Maharashtra Shahir" title (1989) at Apna Utsav.

Despite these, Umap often lamented the government's indifference to folk artists, a sentiment echoed in media reports of his housing struggles.

Death and Legacy

On November 27, 2010 (some sources say November 26), at age 79, Umap collapsed from a heart attack mid-performance at a cultural event in Dikshabhoomi, Nagpur—poetically dying on stage as he had wished. He was rushed to a nursing home but declared dead on arrival. Thousands mourned, with tributes from across Maharashtra; his funeral in Mumbai drew filmmakers like Jabbar Patel.

Umap's legacy endures as a pioneer of Ambedkarite shahiri, having enriched Marathi literature and folk music with over a thousand songs that "brought prosperous days" to Dalit expression. His sons continue his work, and remixed albums keep his voice alive on streaming platforms. As Gaikwad wrote, Umap's art must be "heard and felt," not just read— a testament to his role in reviving Dalit history through sound. In a 2016 retrospective, he was hailed as a "versatile folk artist remembered for his enthusiasm," ensuring Maharashtra's folk soul beats on. For deeper listening, explore his discography on JioSaavn or YouTube channels dedicated to Marathi folk.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for feedback