Anita Bharti

Anita Bharti (also spelled Anita Bharati or अनिता भारती) is a prominent Dalit feminist writer, poet, short story author, critic, editor, and activist in Hindi literature. She is widely recognized for bringing Dalit women's perspectives to the forefront of Hindi literature, challenging caste hierarchies, patriarchy, and savarna (upper-caste) dominance in both society and literary spaces. Her work blends personal experience, activism, and sharp critique, often drawing from Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's vision of equality and anti-caste struggle.

Background and Personal Life

- Born: February 9, 1965, in Delhi (specifically associated with Seelampur area).

- Roots: Born into a Dalit family in Delhi, with family origins in Uttar Pradesh. She belongs to the Dalit community (historically marginalized and excluded from the Hindu caste system, often referred to as Scheduled Castes/SC in India's reservation system).

- Education: MA and BEd from Delhi University.

- Profession: She has worked as a Hindi lecturer (प्रवक्ता) in Delhi government schools/education department for many years. She has been active in the Dalit movement for over 25–30 years, starting from her student days.

- Activism: Long-time participant in Dalit and women's rights movements. She is associated with organizations like the Dalit Lekhak Sangh (Dalit Writers' Association), where she has served in leadership roles (e.g., general secretary). Her activism addresses intersections of caste, gender, religion, and sexuality.

- Personal note: She has spoken about her inter-caste marriage (to someone from an upper-caste Kshatriya background) and experiences navigating caste in personal life.

Literary Contributions and Style

Anita Bharti's writing is radical, grounded in lived Dalit experiences, and often blurs lines between fiction, memoir, fable, and collective memory. She critiques casteism's impact on Dalit women's bodies, lives, and resistance. Her themes include:

- Dalit feminism vs. mainstream (savarna) feminism.

- Structural caste violence, gender inequality, and sexual violence.

- Ambedkarite thought, love in the context of caste, and anti-caste struggles.

Key works include:

- Short story collections: Ek Thi Kotewali (एक थी कोटेवाली / Chronicle of the Quota Woman and Other Stories) — explores casteism in education/reservations and Dalit women's lives; translated into English and awarded the PEN Presents award in 2022.

- Poetry collections: Ek Kadam Mera Bhi (एक कदम मेरा भी); Rukhsana ka Ghar (रुखसाना का घर) — a series on sexual violence during events like the Muzaffarnagar riots.

- Critical/analytical works: Samkaleen Nariwad aur Dalit Stree ka Pratirodh (समकालीन नारीवाद और दलित स्त्री का प्रतिरोध) — critiques contemporary feminism from a Dalit woman's standpoint.

- Edited volumes: Yathastithi se Takraate Hue Dalit Stree Jeewan se Judi Kavitaayein (यथास्थिति से टकराते हुए दलित स्त्री जीवन से जुड़ी कविताएँ) — pioneering anthology of poems by 65 poets on Dalit women's realities.

- Biography: On social revolutionary Gabdu Ram Valmiki (गब्दूराम वाल्मीकि).

- Other: Autobiography excerpts or related works like Chhute Pannon ki Udaan; contributions to anthologies on Dalit love stories, cuisine critiques (e.g., "There is No Dalit Cuisine"), and more.

Her stories and poems often highlight resistance ("We fight!"), political activism's strains on personal relationships, and the need to dismantle caste through literature.

Awards and Recognition

She has received several honors for her writing, teaching, and activism, including:

- Radhakrishan Shikshak Puraskar

- Indira Gandhi Shikshak Samman

- Delhi Rajya Shikshak Samman

- Birsa Munda Samman

- Jhalkari Bai Rashtriya Sewa Samman

- International recognition: PEN Presents award (2022) for her translated short stories.

Overall Impact

Anita Bharti is a leading voice in Dalit literature and Dalit feminism in the Hindi belt. She advocates breaking caste "fortresses" in literature, amplifying marginalized voices, and building solidarities among Dalit, Adivasi, and other oppressed women. Her work continues to inspire anti-caste and feminist discourse, emphasizing that Dalit literature is inherently a struggle against casteism and all forms of inequality.

She remains active on platforms like Facebook (@anitabharti) and contributes to discussions on Ambedkar, women's rights, and social justice.

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka (October 7, 1934 – January 9, 2014), born Everett Leroy Jones, was a transformative African American poet, playwright, essayist, fiction writer, music critic, and activist whose provocative, revolutionary works chronicled the rage, resilience, and cultural richness of Black life in America. Often hailed as the father of the Black Arts Movement—the aesthetic arm of the Black Power era—Baraka's oeuvre spanned over 50 books and nearly six decades, blending jazz rhythms, street vernacular, and unflinching social critique to challenge racism, imperialism, and cultural erasure. His evolution from Beat-influenced bohemian to Black nationalist and finally Marxist revolutionary mirrored the turbulent shifts in 20th-century Black liberation, earning him both adoration as a literary giant and sharp criticism for his polarizing rhetoric.

Early Life and Education

Baraka was born in Newark, New Jersey, to Coyt Leroy Jones, a postal supervisor and lift operator, and Anna Lois Russ, a social worker who had been the first Black woman to graduate from the New Jersey College for Women (now Douglass College). Raised in a middle-class family, he attended Barringer High School, where he excelled in poetry and jazz, idolizing musicians like Miles Davis and dreaming of emulating their cool sophistication. In 1951, he enrolled at Rutgers University on a scholarship but felt alienated by its predominantly white environment and transferred to the historically Black Howard University in 1952, studying philosophy and religious studies while running cross-country. He left Howard without a degree in 1954, later auditing classes at Columbia University and The New School in New York.

Military Service and Early Career

In 1954, Baraka enlisted in the U.S. Air Force as a gunner, serving in Puerto Rico and reaching the rank of sergeant by 1957. His time there was fraught; he later called the military "racist, degrading, and intellectually paralyzing." Stationed at a base library, he devoured literature and began writing poetry inspired by Beat writers. His service ended in a dishonorable discharge after authorities discovered Soviet writings in his possession, accusing him of violating his oath of duty—a charge he contested as pretextual. Discharged, Baraka moved to Greenwich Village in 1957, immersing himself in the bohemian scene, working odd jobs like warehouse stocking for a music distributor, and deepening his passion for avant-garde jazz and poetry.

Greenwich Village Period and First Marriage

In the late 1950s, writing as LeRoi Jones, Baraka became a fixture among the New York School and Black Mountain poets, befriending figures like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Frank O'Hara, and Gilbert Sorrentino. In 1958, he married Hettie Cohen, a white Jewish printer, and together they founded Totem Press, publishing Beat luminaries, and the quarterly Yugen (1958–1962), which showcased experimental work. They also co-edited The Floating Bear (1961–1963) with Diane di Prima, facing obscenity charges in 1961 over a William Burroughs excerpt. Baraka co-founded the New York Poets Theatre in 1961 and had an affair with di Prima, resulting in a daughter, Dominique (b. 1962). This period produced his debut poetry collection, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (1961), a raw exploration of alienation and existential dread, and his seminal music criticism Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963), which traced Black music as a form of resistance.

Political Awakening and Name Change

A pivotal 1960 trip to Cuba with the Fair Play for Cuba Committee radicalized Baraka, exposing him to third-world revolutions and prompting his essay "Cuba Libre," which critiqued American imperialism. The 1965 assassination of Malcolm X shattered him further, leading to a profound break: he left his Village life, divorced Cohen (with whom he had daughters Kellie, b. 1959, and Lisa, b. 1961), and moved to Harlem. In 1967, he adopted the name Imamu Ameer Baraka (later simplified to Amiri Baraka), with "Amiri" meaning "Prince" in Arabic and "Baraka" signifying "blessing" or "divine favor" in Swahili. This marked his embrace of Black cultural nationalism, viewing art as a weapon for liberation: "I still see art as a weapon and a weapon of revolution."

Black Arts Movement and Activism

Baraka founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BART/S) in Harlem in 1965, funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity, to nurture Black artists and stage revolutionary works—though it closed in 1966 amid funding cuts and internal strife. He returned to Newark, establishing the Spirit House (a cultural center and theater troupe) and co-founding the Black Community Development and Defense Organization, becoming a key figure in Newark's Black political scene. By 1968, he identified as Muslim, adding "Imamu" ("spiritual leader"), but by 1974, disillusioned with nationalism's racial focus, he shifted to Marxism-Leninism, influenced by Maoism and global anti-colonial struggles. He ran unsuccessfully for Newark's city council in 1968 and co-founded the Congress of African People in 1970, later the National Black Political Convention.

Major Works

Baraka's output was prolific and genre-spanning, often infused with jazz scatting, polemical fury, and historical reckoning.

- Poetry: Collections like The Dead Lecturer (1964), Black Magic (1969), It's Nation Time (1970), Transbluesency: Selected Poems (1995), Funk Lore (1996), and the posthumous S O S: Poems 1961–2013 (2015). Standouts include "The Music: Reflection on Jazz and Blues" and "Somebody Blew Up America" (2003), a post-9/11 rant questioning U.S. foreign policy.

- Plays: Dutchman (1964), an Obie Award-winner critiquing racial seduction and violence; The Slave (1964); Four Black Revolutionary Plays (1969); and experimental works like A Black Mass (1966), blending myth and revolution.

- Fiction and Essays: Novels such as The System of Dante's Hell (1965) and Tales of the Out & the Gone (2006); essays in Home: Social Essays (1966) and Raise Race Rays Raze (1972); and his autobiography The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka (1984).

His style evolved from introspective surrealism to agitprop, always rooted in Black vernacular and music: "That gorgeous chilling sweet sound... them blue African magic chants."

Teaching Career

From 1979 until his 2002 retirement, Baraka was a professor of Africana Studies at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, also teaching at Yale, Columbia, San Francisco State, and the New School. He mentored generations, emphasizing Black aesthetics and history.

Controversies

Baraka's unapologetic voice drew fire: early works faced obscenity trials; his nationalism was accused of misogyny and homophobia; later Marxist phase included anti-Semitic tropes, notably in "Somebody Blew Up America," which implied Jewish/Israeli complicity in 9/11, costing him New Jersey's poet laureate post in 2002. He defended his words as "revolutionary truth," but critics like Henry Louis Gates Jr. decried them as divisive.

Later Life, Family, and Death

In 1965, Baraka married Sylvia Robinson (later Amina Baraka), with whom he had four children: Obalaji, Ras Baraka (Newark's mayor since 2013), Ayodele Zenari, and Shani Isis. He remained Newark-based, active in local politics and writing until a 2013 hospitalization for a hospital-acquired infection led to his death at age 79. Amina and his six children survived him.

Legacy

Aravinda Malagatti

Born 1 May 1956

Bijapur,

Bijapur District,

Mysore State,

(now in Karnataka,

India).

815 Milstein Center / Office Hours: Wednesdays 3:00-5:00 PM

Contact

212-854-8547

arao@barnard.edu

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Adwaita Mallabarman

Native name

অদ্বৈত মল্লবর্মণ

Born January 1, 1914

Brahmanbaria District, Bengal Presidency, British India

Died April 16, 1951 (aged 37)

Alma mater Comilla Victoria College

Occupation Literary editor, writer

Works Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1956)

Adwaita Mallabarman (alternative spelling Advaita Mallabarmana; 1 January 1914 – 16 April 1951) was a Bengali Indian writer. He is mostly known for his novel Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Titash) published in the monthly Mohammadi five years after his death.

Early life and education

Anuj Lugun

1. Biographical Snapshot

Tribe & Origin: He belongs to the Oraon tribe (Kurukh community), classified as a Scheduled Tribe (ST). He hails from Sisai in the Gumla district of Jharkhand, a region rich in Adivasi culture and history but marked by displacement and conflict. Born 10 January 1986 Jaldega Pahantoli, district Simdega, Jharkhand

Language: Writes primarily in Hindi, but his idiom is infused with the rhythms, metaphors, and lived reality of his tribal homeland.

2. Core Themes & Poetic Vision

Lugun’s poetry is a political and cultural act. It moves beyond mere personal expression to become a chronicle of his community's collective experience.

Adivasi Identity & Alienation: His work relentlessly explores the pain of being rendered a "stranger" in one's own land. He writes about the loss of language, culture, and the psychological schism created by forced assimilation and displacement.

Dispossession & Development: A central theme is the critique of predatory "development" and industrialization that strips Adivasis of their forests, lands, and rivers (like the Koel river in Jharkhand). His poetry gives voice to the trauma of being uprooted.

Resistance & Resilience: His poems are not just laments; they are acts of defiance. They document and celebrate Adivasi resistance movements (like the Pathalgadi movement), heroes (like Birsa Munda and Sidho-Kanho), and the unbroken spirit of his people.

Ecological Consciousness: For Lugun, the forest is not a resource but a living, breathing cosmology. His poetry laments its destruction and asserts an inseparable bond between Adivasi life and nature, presenting an alternative to exploitative environmental paradigms.

Love & the Personal: Interwoven with these political themes is a deep, often melancholic, strand of personal love poetry. This love is frequently framed within the landscape of his homeland, making the personal and political inextricably linked.

3. Major Published Works

Pahad Par Lalten (लालटेन पहाड पर / The Lantern on the Mountain): His most celebrated and influential collection. The title symbolizes a fragile but persistent light of hope and consciousness in the dark, mountainous terrain of struggle.

Other Notable Works:

Pandrah Kavitayen,Johar,Pipra Pakhad. His poems are widely anthologized in collections of contemporary Hindi and Indian poetry.

4. Style & Literary Significance

Imagery: Uses stark, powerful, and often starkly beautiful imagery drawn directly from the Adivasi world—forests, rivers, axes, mountains, spirits (bhuts), wounds, and lanterns.

Tone: Ranges from elegiac and haunting to fiercely polemical. There is a consistent undercurrent of anguish, but also a steely determination.

Position in Literature: He is a pivotal figure in the "Adivani" (Adivasi voice) movement in Indian literature. He, along with other poets like Jacinta Kerketta (who writes in Hindi) and writers in various Indian languages, has carved out a distinct literary space that challenges the mainstream, often Savarna (upper-caste), narrative of Indian poetry.

5. Recognition & Impact

Awards: He is a recipient of the "Bharat Bhushan Agarwal Award" for Hindi poetry.

Influence: His work is critically acclaimed and studied as essential reading for understanding contemporary socio-political poetry in India. He is a frequent and powerful speaker at literary festivals, academic seminars, and cultural forums.

Role: More than just a poet, Anuj Lugun is considered an intellectual and cultural ambassador for Adivasi issues. His poetry serves as a crucial historical and emotional record.

6. A Sample of His Voice

To understand his essence, consider these lines (in translation):

"They ask for my address...I say—the forest that you erased from the map,the river whose name you changed in your documents,the mountain you have drilled into and hollowed out.That is my address."

This quintessentially Lugun verse encapsulates the themes of erasure, displacement, and a defiant claim to a stolen homeland.

In Summary

Writer Anuja Chauhan

Writer Anuja ChauhanAnant Rao Akela

Anant Rao Akela (born September 30, 1960), also known as A.R. Akela, is a prominent Indian Dalit writer, poet, folk singer, publisher, and activist from the Jatav community (a Scheduled Caste group in Uttar Pradesh, historically associated with leatherwork). His life and work are deeply rooted in the struggles of Dalit communities, particularly the Jatavs, and are shaped by the Ambedkarite movement for social justice and Bahujan empowerment. As a multifaceted figure, Akela has used literature, music, and political activism to challenge caste oppression, amplify marginalized voices, and preserve Dalit cultural identity. Through his publishing house, Anand Sahitya Sadan, he has become a pivotal force in disseminating Dalit literature. Below is a comprehensive overview of his life, contributions, and significance.

Early Life and Background

- Birth and Family: Born on September 30, 1960, in Paharipur village, Aligarh district, Uttar Pradesh, Akela was raised in a Jatav family that once held significant land but fell into poverty. His grandfather owned approximately 180 acres, a rare asset for a Dalit family, but natural calamities (floods from the Kali River) and disputes with upper-caste landlords eroded their holdings. By the time Akela was born, his father was left with little land, and his death when Akela was 14 plunged the family into further hardship. This experience of land loss and economic marginalization profoundly shaped Akela’s worldview and writings.

- Caste Context: The Jatav community, a sub-caste of Chamars, is classified as a Scheduled Caste (SC) and has faced historical untouchability and exclusion. Despite this, Jatavs have been at the forefront of Dalit political and cultural movements in Uttar Pradesh, producing leaders like Kanshi Ram and Mayawati. Akela’s Jatav identity informs his fierce critique of Brahminical hegemony and his pride in Dalit resilience.

- Education: A school dropout after Class 8 due to financial constraints, Akela was largely self-educated. He immersed himself in the works of B.R. Ambedkar, Jyotirao Phule, and other anti-caste thinkers, which fueled his literary and political awakening. His lack of formal education did not hinder his intellectual growth; instead, it grounded his work in the lived realities of rural Dalit life.

Literary Career

Akela’s literary output spans poetry, pamphlets, essays, biographies, and folk songs, all infused with a militant Ambedkarite ethos. His writings are both a call to action for Dalit empowerment and a critique of casteist structures embedded in Indian society, particularly in Hindu mythology and rural power dynamics. He is a key figure in Dalit literature, a genre that emerged in the 20th century to articulate the experiences of Scheduled Castes and challenge mainstream literary norms.

Key Works

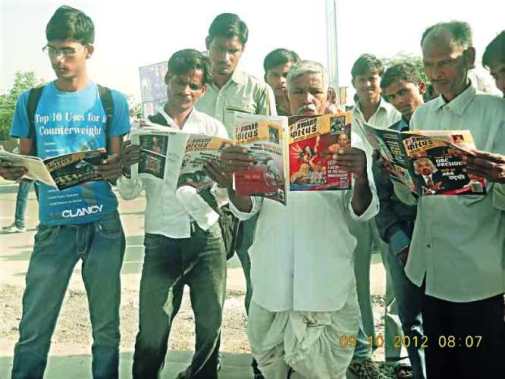

- Poetry and Songs: Akela’s poem Sunlo mutthi bhar insaan (Listen, handful of humans) became an anthem at BSP rallies in the 1980s–1990s, stirring Dalit audiences with its call for dignity and resistance. His folk songs, performed at village fairs and political gatherings, use satire to mock upper-caste landlords and religious hypocrisy. These works draw heavily on Jatav oral traditions and rural metaphors, such as the Kali River’s floods symbolizing erased Dalit histories.

- Style and Themes: Akela’s writing is direct, unpolished, and rooted in the vernacular, making it accessible to Dalit audiences. He critiques the “Brahminical” narratives in texts like the Ramayana, portraying them as tools to justify caste hierarchies. His poetry often invokes Ambedkar’s vision of equality and Buddhist ethics, rejecting victimhood for empowerment.

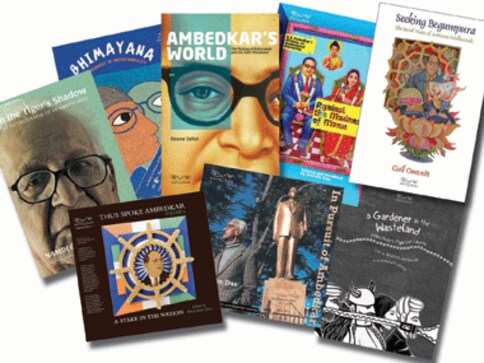

- Publishing: Through Anand Sahitya Sadan, founded in Aligarh, Akela has published hundreds of Dalit-authored works, including pamphlets, books, and magazines. His publishing house is a vital platform for emerging Dalit writers, ensuring their voices reach wider audiences. It also distributes Ambedkar’s writings and Bahujan literature, countering mainstream publishing’s neglect of subaltern narratives.

Literary Significance

Akela’s work is part of the broader Dalit literary movement, alongside figures like Namdeo Dhasal and Raja Dhale (co-founders of the Dalit Panthers). Unlike the urban, modernist tone of some Dalit writers, Akela’s rural Jatav perspective emphasizes agrarian struggles—land loss, bonded labor, and village caste dynamics. His songs and poems, often performed orally, bridge literature and activism, making him a cultural icon for Uttar Pradesh’s Dalit youth.

Activism and Political Involvement

Akela’s literary career is inseparable from his political activism, particularly with the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which he joined in 1985 under the mentorship of Kanshi Ram, the party’s founder. His contributions to the BSP and broader Dalit-Bahujan movements include:

- Role in BSP: Akela was a grassroots mobilizer, using his poetry and folk songs to rally Dalit voters during the BSP’s rise in the 1980s–1990s. His performances at rallies electrified crowds, spreading Kanshi Ram’s vision of a “bahujan” (majority) coalition uniting Dalits, OBCs, and minorities. His loyalty to Kanshi Ram remained unwavering, even as the BSP faced internal conflicts.

- Critique of Leadership: By the 2000s, Akela grew critical of Mayawati’s leadership, accusing her of diluting Kanshi Ram’s anti-caste mission for electoral gains (e.g., aligning with upper-caste parties). In 2015, he co-formed the Kanshi Ram Bahujan Unity Front with other loyalists to revive the BSP’s original ethos, focusing on Dalit land rights and economic justice.

- Land and Caste Advocacy: Akela’s activism often addresses land dispossession, a personal and communal issue for Jatavs. He has supported campaigns to reclaim Panchami lands (allocated to Dalits in the colonial era) and other government-granted plots lost to upper-caste encroachments. His writings link landlessness to caste oppression, echoing Ambedkar’s call for economic empowerment.

Akela’s activism extends beyond politics to cultural spaces. As a folk singer, he performed at melas (fairs) and community events, using music to educate rural Dalits about their rights. His satirical songs target casteist landlords and religious figures, making him a folk hero among Jatav communities.

Challenges and Controversies

- Economic Struggles: Despite his cultural influence, Akela has faced financial precarity, a common challenge for Dalit writers reliant on small-scale publishing. Anand Sahitya Sadan operates with limited resources, yet Akela prioritizes accessibility over profit.

- Political Tensions: His public criticism of Mayawati and BSP’s post-Kanshi Ram trajectory alienated him from party mainstreams, limiting his political influence. However, he remained a respected voice among Kanshi Ram loyalists.

- Caste-Based Retaliation: As a Jatav writer openly challenging upper-caste narratives, Akela has faced social ostracism and threats, particularly in rural Aligarh, where caste violence persists. His bold critiques of Hindu texts like the Ramayana have sparked backlash from conservative groups.

Legacy and Impact

At 65 (as of September 30, 2025), Akela remains active in Aligarh, running Anand控制器

System: Anand Sahitya Sadan and continuing his literary and activist work. His contributions have left a lasting mark on Dalit literature and the Bahujan movement:

- Cultural Icon: Akela’s poems and songs are part of Uttar Pradesh’s Dalit oral tradition, passed down in Jatav communities. His publishing house has preserved countless Dalit voices, making him a cornerstone of the movement’s intellectual infrastructure.

- Ambedkarite Vision: His unwavering commitment to Ambedkar’s principles—equality, education, and land rights—has inspired a new generation of Dalit activists, including those in organizations like the Bhim Army.

- Recognition: While not as globally known as figures like Raja Dhale, Akela is celebrated in Dalit literary circles. His 2015 Hindustan Times profile highlighted his role as a “voice of the voiceless,” and recent X posts (2025) on his birthday laud his contributions to Jatav pride.

Recent Developments

- In recent years, Akela has focused on mentoring young Dalit writers and expanding his publishing efforts. Social media posts (e.g., X, 2023–2025) show him speaking at Ambedkarite events, advocating for land reforms and Buddhist conversion as paths to liberation.

- He has expressed concern about the dilution of Dalit movements by mainstream politics, urging youth to read Ambedkar directly (echoing Raja Dhale’s later views).

Personal Life

Little is publicly documented about Akela’s family, as he keeps his personal life private, focusing on his public roles as a writer and activist. He resides in Aligarh, maintaining close ties to his Jatav community and rural roots. His Buddhist faith, adopted in line with Ambedkar’s 1956 conversion movement, shapes his ethical outlook, emphasizing compassion and resistance.

Significance in Dalit Literature

Boyi Bhimanna

Boyi Bhimanna (1911–2005), often spelled Bheemanna, was a pioneering Telugu poet, writer, and social activist. He is revered as one of the most important Dalit voices in 20th-century Telugu literature, using his powerful writing to expose the brutalities of caste oppression and champion human dignity.

Basic Profile:

Full Name: Boyi Bhimanna

Pen Name: "Bhumika"

Born: 19 September 1911 , Kappagal village, Bellary district (in the Madras Presidency, now in Karnataka).

Died: 16 December 2005

Primary Language: Telugu

Key Identity: Dalit writer from the Boyi (Boya) community (Scheduled Caste in Andhra Pradesh/Telangana).

Historical and Social Context

Bhimanna was born into a deeply oppressive caste hierarchy. The Boyi community, traditionally associated with hunting and labor, faced severe social ostracization and economic exploitation. His personal experiences with untouchability, poverty, and humiliation became the raw material for his literature. He transformed his pain into a weapon of social critique.

Literary Career and Major Themes

His writing is characterized by its directness, raw emotion, and revolutionary spirit. He broke away from classical Telugu literary conventions to write in an accessible, often colloquial style, ensuring his message reached the masses.

Central Themes in his work:

Anti-Caste Revolution: His primary theme was a scathing attack on the caste system. He named caste oppression explicitly, which was a radical act at the time.

Dalit Consciousness and Pride: He wrote to awaken a sense of identity, self-respect, and anger among Dalits, urging them to reject subjugation.

Social Justice & Humanism: His poetry is a cry for equality, dignity, and basic human rights for all marginalized people.

Condemnation of Hypocrisy: He fiercely criticized the hypocrisy of upper-caste society, its rituals, and its exploitation masked by tradition.

Celebration of Labor: He often glorified the labor of Dalit and working-class communities, depicting it as the true foundation of society.

Major Works

Poetry Collections:

Koraga (1994) – His most celebrated work, for which he won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1995. The title refers to a marginalized tribal community, symbolizing all oppressed people.

Gapulamma – A seminal work where the titular Goddess "Gapulamma" represents the spirit of the Dalit mother/land, crying out against injustice.

Mallepuvvu (Jasmine Flower)

Bhumika (published under his pen name)

Autobiography:

Naa Alludu (My Son-in-Law) – A powerful autobiographical narrative that details his personal life and struggles against casteism.

Other Writings: Essays, short stories, and critical articles focused on social issues.

Legacy and Honors

Sahitya Akademi Award (1995): The national award for Koraga was a landmark moment, representing official recognition for Dalit literature in Telugu.

Father of Dalit Poetry in Telugu: He is credited with laying the groundwork for the modern Dalit literary movement in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

Inspiration: He inspired generations of subsequent Dalit writers like Jupaka Subhadra, Gaddar, Sivasagar, and many others.

Cultural Icon: His poems are recited at Dalit rallies and cultural gatherings. They have been adapted into songs and performances by revolutionary balladeers.

A Sample of His Voice (Thematic Translation)

His poetry is known for its stark imagery. For example, he famously challenged the idea of "pollution":

"If my touch pollutes your water,Remember, it is my labor that dug your well."

This couplet encapsulates his entire philosophy: turning the notion of "purity" on its head and asserting the dignity of the laborer.

Conclusion

Boyi Bhimanna was not just a writer; he was a social revolutionary who used poetry as a tool for liberation. He gave a fierce, articulate, and unforgettable voice to the anguish and aspirations of Dalits. His work shifted the landscape of Telugu literature, forcing it to confront social reality and making him an immortal icon in the fight for social justice.

Bojja Tharakam

Bojja Tharakam (1939–2016) was a towering figure in Indian literature, law, and activism, renowned for his contributions as a writer, poet, lawyer, and Dalit rights advocate. His life and work were deeply intertwined with the struggle against caste oppression and for social justice in India, particularly in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Below is a comprehensive overview of his life, contributions, and legacy.

Early Life and Background

- Birth and Family: Bojja Tharakam was born in 1939 in Cheruvukommupalem, a village in East Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh. His father was a first-generation leader in the Scheduled Caste Federation (SCF), founded by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, which shaped Tharakam’s early exposure to anti-caste ideology. He belonged to the Dalit community, classified as a Scheduled Caste in India.

- Education: Tharakam pursued higher education with determination, earning a degree in law. His academic journey was significant, as access to education for Dalits was limited during his time due to systemic caste-based discrimination.

Career as a Lawyer

- Legal Advocacy: Tharakam became a prominent lawyer, practicing in Hyderabad and other courts in Andhra Pradesh. He was known for taking up cases involving caste atrocities, defending Dalit victims, and challenging systemic injustices.

- High-Profile Cases: He played a crucial role in seeking justice for victims of caste-based violence, notably in the Karamchedu massacre (1985), where Dalits were brutally attacked by dominant caste members, and the Tsundur massacre (1991), another horrific instance of caste violence. Tharakam’s legal work extended to filing public interest litigations (PILs) to address systemic issues like reservations and land rights for Dalits.

- Human Rights Advocacy: As a senior advocate, he used the legal system to fight for the rights of marginalized communities, earning a reputation as a fierce defender of justice.

Literary Contributions

- Writer and Poet: Tharakam was a prolific writer and poet, primarily in Telugu, whose works reflected his commitment to social justice and the Dalit cause. His writings often critiqued caste oppression, untouchability, and societal inequalities.

- Notable Works:

- "Panchayati Raj": A book that examined local governance and its implications for marginalized communities.

- "Aatmagauravam" (Self-Respect): A collection of poetry that emphasized Dalit pride, resilience, and the fight for dignity.

- "Naaloni Manishi" (The Man Within Me): A reflective work blending personal and political themes of caste and identity.

- "Mahad Dalita Mahatmyam": A work celebrating the historical significance of the Mahad Satyagraha led by Ambedkar, focusing on Dalit empowerment.

- Style and Themes: His poetry and prose were marked by a powerful, direct style, often drawing from Ambedkarite ideology and his own experiences as a Dalit. His works aimed to inspire resistance against caste oppression and foster a sense of self-worth among Dalits.

- Influence: Tharakam’s writings contributed significantly to Telugu Dalit literature, aligning with the broader Dalit literary movement that sought to amplify marginalized voices. His works remain influential in academic and activist circles.

Activism and Leadership

- Dalit Movement: Tharakam was a leading figure in the Dalit movement in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. He was instrumental in founding and leading the Andhra Pradesh Dalita Mahasabha in 1985, an organization dedicated to Dalit rights and empowerment.

- Ambedkarite Ideology: A staunch follower of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Tharakam promoted Ambedkar’s vision of annihilation of caste, equality, and social justice. He organized rallies, seminars, and protests to spread Ambedkarite thought.

- Key Campaigns:

- Karamchedu and Tsundur Massacres: Tharakam was at the forefront of mobilizing protests and legal battles following these atrocities, demanding accountability and systemic change.

- Reservations and Land Rights: He advocated for the proper implementation of reservations for Dalits in education and employment and fought for land redistribution to landless Dalit families.

- Political Engagement: While primarily an activist, Tharakam briefly engaged with political platforms, including supporting movements for Telangana statehood, though he remained critical of mainstream political parties for their neglect of Dalit issues.

Personal Life and Character

- Family: Little is documented about Tharakam’s personal life, but his family background was deeply rooted in anti-caste activism, with his father being an SCF leader. His commitment to the Dalit cause often meant prioritizing activism over personal pursuits.

- Personality: Tharakam was known for his fearless demeanor, sharp intellect, and unwavering commitment to justice. Colleagues and activists described him as a mentor who inspired younger generations of Dalit leaders and writers.

- Challenges: As a Dalit activist and lawyer, Tharakam faced significant hostility from dominant caste groups and systemic barriers within the legal and social systems. Despite this, he remained resolute in his mission.

Legacy and Impact

- Death: Bojja Tharakam passed away on September 20, 2016, in Hyderabad due to illness. His death was widely mourned by Dalit activists, writers, and human rights advocates across India.

- Influence on Dalit Movement: Tharakam’s work laid the foundation for subsequent generations of Dalit activists in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. His leadership in the Andhra Pradesh Dalita Mahasabha galvanized the Dalit community to demand their rights.

- Literary Legacy: His writings continue to be studied in Telugu literature and Dalit studies, serving as a source of inspiration for those fighting caste oppression.

- Recognition: Tharakam was posthumously celebrated for his contributions to law, literature, and activism. His life is often cited as an example of how intellectual rigor and grassroots activism can converge to challenge systemic inequalities.

Key Contributions Summarized

- Legal Advocacy: Defended Dalit victims in landmark cases like Karamchedu and Tsundur, using the law as a tool for justice.

- Literary Voice: Authored powerful works in Telugu that gave voice to Dalit experiences and aspirations.

- Activism: Founded the Andhra Pradesh Dalita Mahasabha and led protests against caste atrocities.

- Ambedkarite Leadership: Promoted Ambedkar’s vision of caste annihilation and social equality.

Conclusion

Bojja Tharakam was a multifaceted figure—a lawyer who fought for justice, a writer who gave voice to the oppressed, and an activist who carried forward Ambedkar’s legacy. His contributions to the Dalit movement, Telugu literature, and the fight against caste oppression remain a beacon for social justice advocates. His life exemplifies the power of combining intellectual pursuits with grassroots activism to challenge systemic inequalities.

Bandhu Madhav

Early Life & Identity

- Anonymous by Necessity: Bandhu Madhav wrote under a pseudonym to protect his government job and family from caste retaliation.

- Mahar Background: Born into the Mahar community in rural Maharashtra (likely Konkan or Vidarbha region), a caste historically subjected to untouchability, forced labor, and social exclusion.

- Government Employee: Served as a Police Sub-Inspector, a rare achievement for a Mahar in pre-independence and early post-independence India due to systemic barriers.

- Education: Self-educated in Marathi literature; influenced by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Jyotirao Phule, and Buddhist thought.

Literary Career

- First Appearance: His story "The Poisoned Bread" was published in 1959 in a Marathi magazine.

- Breakthrough Anthology: Included in "Poisoned Bread: Translations from Modern Marathi Dalit Literature" (edited by Arjun Dangle, 1992), which introduced Dalit writing to English readers worldwide.

- Writing Style:

- Raw, direct, and unapologetic.

- Based on lived experience of caste violence.

- No romanticization of village life or upper-caste benevolence.

"The Poisoned Bread" – The Landmark Story

- Plot Summary:

- A Mahar elder is forced by upper-caste villagers to eat bread contaminated with human feces as punishment for accidentally touching a vessel.

- He dies in agony, but his son vows resistance.

- Symbolism:

- Bread = Livelihood and dignity

- Poison = Caste oppression

- Impact:

- Shocked Marathi literary circles.

- Challenged the "rural harmony" myth in mainstream Marathi writing.

- Became the title story of the seminal Dalit anthology.

Role in Dalit Literary Movement

| Contribution | Details |

|---|---|

| Pioneer | Among the first Mahars to write fiction in Marathi post-1947 |

| Ambedkarite Influence | Promoted Buddhist rationalism and anti-caste ideology |

| Published In | Janata, Prabuddha Bharat, Asmitadarsh – key Dalit-Buddhist journals |

| Mentored | Inspired younger writers like Baburao Bagul, Namdeo DhasalWhy He Remained Anonymous |

- Job Security: Government servants faced dismissal for "political" writing.

- Caste Backlash: Risk of violence from dominant castes in villages.

- Movement Strategy: Many early Dalit writers used pen names (e.g., Anna Bhau Sathe as "Navayan") to focus on message over individual fame.

Legacy

- Posthumous Recognition:

- His real name remains unknown or unconfirmed in most records.

- Honored as a "founding ancestor" of Dalit literature.

- Academic Study:

- Analyzed in works like Dalit Literatures in India (ed. Joshil K. Abraham & Judith Misrahi-Barak).

- Taught in Maharashtra Board Marathi textbooks (abridged version).

- Cultural Impact:

- Inspired Dalit Panthers (1972) and anti-caste theater.

- Translated into Hindi, Tamil, and Kannada.

Key Quotes (from "The Poisoned Bread")

"They fed him bread laced with poison. He ate it. And died. But the poison did not kill him. It awakened a thousand others."

"We do not beg for justice. We seize it with our words."

Recommended Reading

- Poisoned Bread (Anthology, Orient BlackSwan, 1992) – Full text of the story

- Towards an Aesthetic of Dalit Literature – Sharankumar Limbale

- Dalit Visions – Gail Omvedt

Why He Matters Today

- Broke the Silence: First to document caste atrocities in fiction from a Mahar perspective.

- Precursor to Ambedkarite Literature: Bridged Phule-Ambedkar thought with creative writing.

- Symbol of Resistance: A government servant who used his pen as a weapon against the system he served.

In the words of Arjun Dangle (editor):"Bandhu Madhav did not just write a story. He detonated a bomb in Marathi literature."

Though his real name is lost to history, Bandhu Madhav remains immortal as the first whisper of the Dalit literary storm.

Balswaroop Raahi

Born 16 May 1936

Timarpur New Delhi

Occupation Poet, lyricist

Literary career

Bibliography

Novels

Teekavamarsh. Aurngabad : Rajat 2010

Samiksha Up Haran. Aurangabad Rajat 2010

Sahitya vimarsh Maranam . Pune Diamond 2011

Samagra Shakespeare: Taulanik Sanskrti Samiksha. Kolhapur : Anand Granthsager 2017

Samagra S. S. Mardhekar: Taulanik Sanskrati Mimam -nsa,Pune: Padmagandha, 2018

Local and Global, Kolhapur Anand Granthsager 2019

Kahi Lobel kahi Globel Anand Granthsagar 2019

English Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies

Western Influence on Marathi Drama. Panaji Rajhanus. 1993

Whirligig of Taste: Essays in Comparative Literature Delhi: Creative Books 1999

Perspectives and Progression. Delhi Creative Books 2005

ddhas Shelke: Makers of Indian Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Academy 2002

Revisioning Comparative Literature and Culture Delhi: Authors Press 2011

Literary Comparative Literative and Cultural Criticism. Foreworeded by Steehen Tostory de Zeptne. Ambala : Associated Press 2011

Interdisciplinary : Literary and Cultural. Kolhapur: Anand Granthsagar 2019

Literary Awards and Appreciation Received by Patil

Awards

H.N. Apte Award for Kagud ani Savali: Government of Maharashtra H.N. Apte Award ,M.S. Parishad, Pune H.N .Apte Award. Best novel of the Decade Selection by Maharashtra Times (1986)

Pune Nagar Wachanalay S.J. Joshi Awards, for Icchamaran. Balapur Library Kondaji Patil Purskar (2008)

SKK Purskar. Taulanik Sahitya: Nave Siddhant ani Uptojan. Government of Maharashtra SKK Purskar.

M.V. Gokhale Award. Marathi Natkawaril Ingraji prbhav, Maharashtra Sahitya Parishad Pune M.V. Gokhale Award (1998)

S.M. Paranjpe Award. British Bombay ani Portuguese Govyatil Wangmay .Maharashtra Sahitya Parishad Pune S.M. Paranjpe Award

Tulav: Tulanik Nibandh, Jansahitya parishad Amravati Award and Vidharbh Sahitya Sangh ugawani awards (1999)

Srajanatamak Lekhan, Government of Maharashtra Kusumavati Deshpande Award 2005

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Baburao Bagul

Born Baburao Ramaji Bagul

17 July 1930

Vihitgaon, Nashik district, Maharashtra

Died 26 March 2008 (aged 77)

Nashik, Maharashtra

Occupation Writer and poet

Notable works Jevha Mi Jat Chorali Hoti! (When I had Concealed My Caste) (1963)

Maran Swasta Hot Ahe (Death is Getting Cheaper) (1969)

Ambedkar Bharat (Ambedkar India) (1981)

Baburao Ramji Bagul (1930–2008) was a Marathi writer from Maharashtra, India; a pioneer of modern literature in Marathi and an important figure in the Indian short story during the late 20th century, when it experienced a radical departure from the past, with the advent of Dalit writers such as him.

He is most known for his works such as, Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti! (1963), Maran Swasta Hot Ahe (1969), Sahitya Ajache Kranti Vigyan, Sud (1970), and Ambedkar Bharat (1981).

Biography

He died on 26 March 2008 at Nashik, and was survived by his wife, two sons, two daughters.

Subsequently, the Yashwantrao Chavan Maharashtra Open University instituted the Baburao Bagul Gaurav Puraskar Award in recognition of his contributions to Marathi literature, to be given annually to the debut work of a budding short-story writer.

Works

"Jevha Mi Jaat Chorali Hoti!" (जेव्हा मी जात चोरली होती!) (1963)

"Maran Swasta Hot Ahe" (मरण स्वस्त होत आहे) (1969)

"Sud" (सूड) (1970)

"Dalit Sahitya Ajache Kranti Vignyan (दलित साहित्य आजचे क्रांतिविज्ञान)

"Ambedkar Bharat" (आंबेडकर भारत) (1981)

Aghori (अघोरी) (1983)

Pashan (पाषाण) (1972)

Apurva (अपूर्वा)

Kondi (कोंडी) (2002)

Pawsha (पावशा) (1971)

Bhumihin (भूमिहीन)

Mooknayak (मूकनायक)

Sardar (सरदार)

Vedaadhi Tu Hotas (वेदाआधी तू होता) [poetry collection]

Dalit Dahitya : Aajche Krantividyan (दलित साहित्य: आजचे क्रांतिविज्ञान)

Translation

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka (October 7, 1934 – January 9, 2014), born Everett Leroy Jones, was a transformative African American poet, playwright, essayist, fiction writer, music critic, and activist whose provocative, revolutionary works chronicled the rage, resilience, and cultural richness of Black life in America. Often hailed as the father of the Black Arts Movement—the aesthetic arm of the Black Power era—Baraka's oeuvre spanned over 50 books and nearly six decades, blending jazz rhythms, street vernacular, and unflinching social critique to challenge racism, imperialism, and cultural erasure. His evolution from Beat-influenced bohemian to Black nationalist and finally Marxist revolutionary mirrored the turbulent shifts in 20th-century Black liberation, earning him both adoration as a literary giant and sharp criticism for his polarizing rhetoric.

Early Life and Education

Baraka was born in Newark, New Jersey, to Coyt Leroy Jones, a postal supervisor and lift operator, and Anna Lois Russ, a social worker who had been the first Black woman to graduate from the New Jersey College for Women (now Douglass College). Raised in a middle-class family, he attended Barringer High School, where he excelled in poetry and jazz, idolizing musicians like Miles Davis and dreaming of emulating their cool sophistication. In 1951, he enrolled at Rutgers University on a scholarship but felt alienated by its predominantly white environment and transferred to the historically Black Howard University in 1952, studying philosophy and religious studies while running cross-country. He left Howard without a degree in 1954, later auditing classes at Columbia University and The New School in New York.

Military Service and Early Career

In 1954, Baraka enlisted in the U.S. Air Force as a gunner, serving in Puerto Rico and reaching the rank of sergeant by 1957. His time there was fraught; he later called the military "racist, degrading, and intellectually paralyzing." Stationed at a base library, he devoured literature and began writing poetry inspired by Beat writers. His service ended in a dishonorable discharge after authorities discovered Soviet writings in his possession, accusing him of violating his oath of duty—a charge he contested as pretextual. Discharged, Baraka moved to Greenwich Village in 1957, immersing himself in the bohemian scene, working odd jobs like warehouse stocking for a music distributor, and deepening his passion for avant-garde jazz and poetry.

Greenwich Village Period and First Marriage

In the late 1950s, writing as LeRoi Jones, Baraka became a fixture among the New York School and Black Mountain poets, befriending figures like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Frank O'Hara, and Gilbert Sorrentino. In 1958, he married Hettie Cohen, a white Jewish printer, and together they founded Totem Press, publishing Beat luminaries, and the quarterly Yugen (1958–1962), which showcased experimental work. They also co-edited The Floating Bear (1961–1963) with Diane di Prima, facing obscenity charges in 1961 over a William Burroughs excerpt. Baraka co-founded the New York Poets Theatre in 1961 and had an affair with di Prima, resulting in a daughter, Dominique (b. 1962). This period produced his debut poetry collection, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (1961), a raw exploration of alienation and existential dread, and his seminal music criticism Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963), which traced Black music as a form of resistance.

Political Awakening and Name Change

A pivotal 1960 trip to Cuba with the Fair Play for Cuba Committee radicalized Baraka, exposing him to third-world revolutions and prompting his essay "Cuba Libre," which critiqued American imperialism. The 1965 assassination of Malcolm X shattered him further, leading to a profound break: he left his Village life, divorced Cohen (with whom he had daughters Kellie, b. 1959, and Lisa, b. 1961), and moved to Harlem. In 1967, he adopted the name Imamu Ameer Baraka (later simplified to Amiri Baraka), with "Amiri" meaning "Prince" in Arabic and "Baraka" signifying "blessing" or "divine favor" in Swahili. This marked his embrace of Black cultural nationalism, viewing art as a weapon for liberation: "I still see art as a weapon and a weapon of revolution."

Black Arts Movement and Activism

Baraka founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BART/S) in Harlem in 1965, funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity, to nurture Black artists and stage revolutionary works—though it closed in 1966 amid funding cuts and internal strife. He returned to Newark, establishing the Spirit House (a cultural center and theater troupe) and co-founding the Black Community Development and Defense Organization, becoming a key figure in Newark's Black political scene. By 1968, he identified as Muslim, adding "Imamu" ("spiritual leader"), but by 1974, disillusioned with nationalism's racial focus, he shifted to Marxism-Leninism, influenced by Maoism and global anti-colonial struggles. He ran unsuccessfully for Newark's city council in 1968 and co-founded the Congress of African People in 1970, later the National Black Political Convention.

Major Works

Baraka's output was prolific and genre-spanning, often infused with jazz scatting, polemical fury, and historical reckoning.

- Poetry: Collections like The Dead Lecturer (1964), Black Magic (1969), It's Nation Time (1970), Transbluesency: Selected Poems (1995), Funk Lore (1996), and the posthumous S O S: Poems 1961–2013 (2015). Standouts include "The Music: Reflection on Jazz and Blues" and "Somebody Blew Up America" (2003), a post-9/11 rant questioning U.S. foreign policy.

- Plays: Dutchman (1964), an Obie Award-winner critiquing racial seduction and violence; The Slave (1964); Four Black Revolutionary Plays (1969); and experimental works like A Black Mass (1966), blending myth and revolution.

- Fiction and Essays: Novels such as The System of Dante's Hell (1965) and Tales of the Out & the Gone (2006); essays in Home: Social Essays (1966) and Raise Race Rays Raze (1972); and his autobiography The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka (1984).

His style evolved from introspective surrealism to agitprop, always rooted in Black vernacular and music: "That gorgeous chilling sweet sound... them blue African magic chants."

Teaching Career

From 1979 until his 2002 retirement, Baraka was a professor of Africana Studies at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, also teaching at Yale, Columbia, San Francisco State, and the New School. He mentored generations, emphasizing Black aesthetics and history.

Controversies

Baraka's unapologetic voice drew fire: early works faced obscenity trials; his nationalism was accused of misogyny and homophobia; later Marxist phase included anti-Semitic tropes, notably in "Somebody Blew Up America," which implied Jewish/Israeli complicity in 9/11, costing him New Jersey's poet laureate post in 2002. He defended his words as "revolutionary truth," but critics like Henry Louis Gates Jr. decried them as divisive.

Later Life, Family, and Death

In 1965, Baraka married Sylvia Robinson (later Amina Baraka), with whom he had four children: Obalaji, Ras Baraka (Newark's mayor since 2013), Ayodele Zenari, and Shani Isis. He remained Newark-based, active in local politics and writing until a 2013 hospitalization for a hospital-acquired infection led to his death at age 79. Amina and his six children survived him.

Legacy

Baraka's indelible mark on Black literature—fusing art and activism—inspired hip-hop, spoken word, and scholars like Cornel West. As he wrote, "If you ain't never had your dick sucked by a nigger in downtown Kansas City, you ain't lived." His work endures as a clarion for the dispossessed, though debates over his excesses persist. Posthumously, collections like The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader (1999) affirm his role as a "poet of the people."

भारत में शुरुआत से ही सिंधु संस्कृती समतावादी, मानवतादी रही है. बाद में चार हजार साल पूर्व में आर्यों ने भारत पर आक्रमण कर के वर्णभेद, जातीभेद निर्माण किया. उसके खिलाफ में तथागत बुध्द, गुरू कबीर, गुरू नानक, गुरू नामदेव, गुरू तुकाराम, गुरू गाडगेबाबा इन्होने आंदोलन किया. बाद में महात्मा फुले, छ.शाहू महाराज, डॉ.बाबासाहब आंबेडकर इन्होने जन-आंदोलन किया. डॉ.बाबासाहब के आंदोलन में अनेक कवी तथा गायकों ने योगदान दिया है. इनमें से वामनदादा कर्डक जी ने बाबासाहब के आंदोलन को गीत-गायन द्वारा पूरे भारत भर फैलाया.

भारत में शुरुआत से ही सिंधु संस्कृती समतावादी, मानवतादी रही है. बाद में चार हजार साल पूर्व में आर्यों ने भारत पर आक्रमण कर के वर्णभेद, जातीभेद निर्माण किया. उसके खिलाफ में तथागत बुध्द, गुरू कबीर, गुरू नानक, गुरू नामदेव, गुरू तुकाराम, गुरू गाडगेबाबा इन्होने आंदोलन किया. बाद में महात्मा फुले, छ.शाहू महाराज, डॉ.बाबासाहब आंबेडकर इन्होने जन-आंदोलन किया. डॉ.बाबासाहब के आंदोलन में अनेक कवी तथा गायकों ने योगदान दिया है. इनमें से वामनदादा कर्डक जी ने बाबासाहब के आंदोलन को गीत-गायन द्वारा पूरे भारत भर फैलाया.पूर्व न्यायाधीश

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Chamarasa (c. 1425) was an eminent 15th century Virashaiva poet in the Kannada language, during the reign of Vijayanagar Empire, a powerful empire in Southern India during 14th - 16th centuries. A contemporary and competitor to a noted Brahmin Kannada poet Kumara Vyasa, Chamarasa was patronised by King Deva Raya II. The work is in 25 chapters (gatis) comprising 1111 six-line verses (shatpadi).

Magnum Opus

खैरमोड़े जी ने अपने स्कूली दिनों में खादी के महत्व को उजागर करने वाली कविता लिखी।

खैरमोड़े जी ने दो सामाजिक प्रवचन लिखे - 'पाटिल प्रताप' (1928) और 'अमृतकण' (1929)। बाद में, सामाजिक सुधार, अस्पृश्यता, हिंदू धर्म और हिंदू समाज जैसे विभिन्न मुद्दों पर उनका वैचारिक लेखन महाराष्ट्र की विभिन्न पत्रिकाओं में प्रकाशित हुआ। 'शूद्र से पहले' कौन थे? (1951), उन्होंने 'उपनिषद और हिंदू महिलाओं का ह्रास' (1961), 'संविधान' पर तीन भाषण' लिखे।

साभार

विकिपीडिया : 8.1.2018

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2041191856171465&id=1703045756652745

Changdev Bhavanrao Khairmode

Changdev Bhavanrao Khairmode, popularly known as Abasaheb Khairmode, was one of the most important Marathi writers, historians, and biographers of the 20th century. He is best remembered as the author of the monumental 14-volume Marathi biography of Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar titled Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Charitravali (1950–1984), widely regarded as the most authoritative and detailed life-history of the architect of India’s Constitution.

Personal Background & Caste

- Born: 15 July 1904

- Place: Panchwad village, Khatav taluka, Satara district, Maharashtra

- Caste / Community: Mahar (Scheduled Caste / Dalit) – one of the largest untouchable communities in Maharashtra that faced extreme social discrimination during the British period.

- Family: Son of Bhavanrao Khairmode (a modest village worker). Married Dwarkabai Gaikwad (also Mahar caste). After his death, his wife completed and published the remaining volumes of the biography.

- Religion: Born Hindu; later converted to Navayana Buddhism along with Dr. Ambedkar’s mass conversion movement in 1956.

Early Life & Education

Khairmode walked several miles daily to attend school because Dalit children were not allowed to sit inside classrooms. Despite humiliation, he excelled academically:

- New English School, Satara

- Graduated with a B.A. in Arts from a college in Bombay (Mumbai) – a rare achievement for a Mahar youth at that time.

- Worked briefly as a clerk in the British Secretariat in Bombay to support himself.

Association with Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

From his student days, Khairmode became a regular visitor to Ambedkar’s office at the newspaper Bahishkrit Bharat (“Excluded India”). He used to study and even sleep there with other Dalit students. This close proximity gave him direct access to Ambedkar’s personal papers, letters, speeches, and memories – material that no other biographer possessed.

Major Literary Works

| Work | Year(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Charitravali (14 volumes) | 1950–1984 | The definitive biography in Marathi. First 4 volumes published in Khairmode’s lifetime; remaining 10 completed and published by his wife Dwarkabai after his death. Total pages exceed 10,000. |

| Asprushyancha Lashkar Pesh | 1950s | Historical book proving that Mahar soldiers formed a significant part of Shivaji’s army, countering upper-caste narratives that erased Dalit contributions. |

| Various essays in Bahishkrit Bharat and other journals | 1920s–1960s |

| Death & Legacy |

- Died: 16 February 1971 (aged 66) in Mumbai

- Completion of biography: Dwarkabai Khairmode devoted the rest of her life to publishing the remaining volumes (Vols. 5–14) between 1972 and 1984.

- Recognition today: – The 14-volume set is still the primary source for scholars studying Ambedkar. – The 2019 Star Pravah Marathi TV serial Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar – Mahamanvachi Gauravgatha was largely based on Khairmode’s biography. – Hindi translations (12 volumes) and abridged English versions are now available. – Statues and libraries named after him in Satara and Pune districts. – Annual remembrance by Ambedkarite organizations on 15 July (birth) and 16 February (death).

Summary

Changdev Bhavanrao Khairmode was a Mahar scholar who rose from extreme poverty and caste oppression to become Dr. Ambedkar’s most trusted biographer. His life’s work preserved the most accurate and detailed record of Ambedkar’s journey, making him an unsung hero of Dalit literature and Indian social history.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dr. Bharati: documentary directed by young story writer Uday Prakash for Sahitya Akademi, Delhi, 1999

Awards

Padma Shri by the Government of India, 1972

Rajendra Prasad Shikhar Samman

Bharat Bharati Samman

Maharashtra Gaurav, 1994

Kaudiya Nyas

Vyasa Samman

1984, Valley turmeric best journalism awards

1988, best playwright Maharana Mewar Foundation Award

1989, the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Delhi

Translations

Andha Yug: Dharamvir Bharati, translated in English by Alok Bhalla, published by Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-567213-8, ISBN 0-19-567213-5

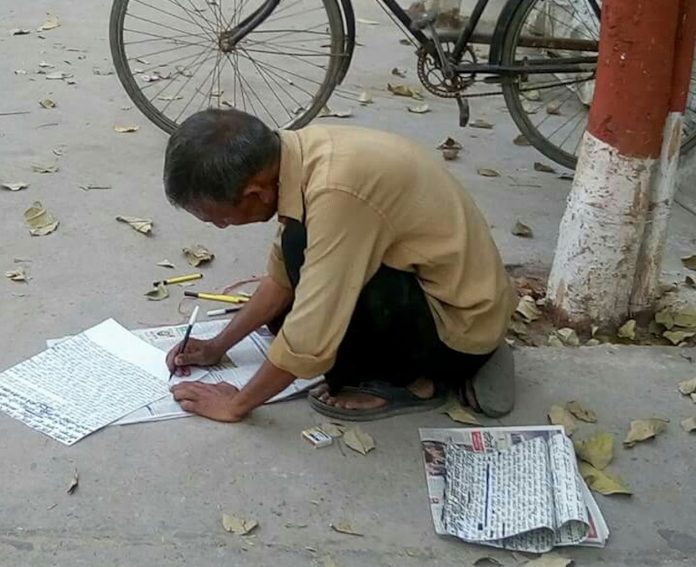

This journalist from Muzaffarnagar is on a mission to educate and spread awareness on 'real issues' via his handwritten newspaper

That's the kind of reporting we all need in our country.

We also spoke to Master Vijay Singh, an anti-corruption activist fighting against the land mafias in Muzzafarnagar, Uttar Pradesh.

He is well connected to the 51-year-old journalist as he sits and writes outside the DM's office with the activist. Here's what he said:

"Dinesh is a passionate man. He always keeps a sketch pen with him to write the stories in the newspaper. He focuses on the real-life issues that are not attended by others."

"He roams in the city to distribute toffees, ice-creams, and chocolates to the children in the afternoon and comes back after that to write stories for the newspaper."

Both are working together for the betterment of the country. We need more of such human beings who can take out the root cause of the issues and deliver the same ground issues to the caretakers of the country.

Without any help or a fixed job, this man is doing good deeds for the society.

The only handwritten newspaper in Urdu

Musalman, the only Urdu handwritten newspaper

Earlier in November 2017, we found that the state of Chennai also has its handwritten newspaper which is largely in black and white and is written in the Urdu language

The Musalman publishes Urdu poetry and messages on devotion to God and communal harmony daily

At this age where the most of the reporting is based on what Taimur has eaten today and what Salman Khan is having for lunch in the jail, Dinesh's story deserves an applaud for talking about the real issues.

Dinesh: The Man Who Is Selling Handwritten Newspapers Since 17 Years

Pic Credit- Daily Hunt

Pic Credit- Daily HuntBy- Md. Mojahid Raza

Bhubaneswar: Media is the most powerful entity in today’s world. It controls the minds of the masses, acts as a watchdog of the society and plays a vital role in social change.In today’s time where media is all about commercialisation of news and information, there still lives a man for whom journalism is not about TRPs and viewership rather a weapon to bring a change by informing and educating the general public.

The 53-year-old Dinesh hails from Muzaffarnagar in Uttar Pradesh. His contribution in the realm of media is unique and has set an unprecedented benchmark. Dinesh has been single-handedly running a newspaper called ‘Vijay Darshan’ since the last 17 years, which he painstakingly writes in his own handwriting.After writing a copy, Dinesh makes multiple photocopies of it, which are later supplied to the readers. He uses his bicycle to travel around the city and distribute newspaper to his customers.

Pic Credit- DailyHunt

Pic Credit- DailyHuntHowever, this isn’t Dinesh’s only occupation. The earnings from newspaper are not sufficient to keep his kitchen stove burning. Hence, Dinesh sells ice-creams and chocolates to make ends meet. He had dreamt of pursuing law but had to drop out of school owing to financial constraints. Later, family responsibility and need for money forced him to do odd jobs for survival. At present, Dinesh single-handedly writes and circulates his newspaper. He works all by his own with no financial or material help from outside.

Pic Credit- DailyHunt

Pic Credit- DailyHunt

It was Dinesh's love for his handwritten Vidya Darshan that never let him get married and have kids. His passion for writing newspaper never benefitted him on a monetary basis, but he has no regrets of choosing it over his good future.

It was Dinesh's love for his handwritten Vidya Darshan that never let him get married and have kids. His passion for writing newspaper never benefitted him on a monetary basis, but he has no regrets of choosing it over his good future.

The Blindness of Insight

Essays on Caste in Modern India

From Wikipedia

D. S. Ravindra Doss (20 November 1945 – 22 June 2012) was a senior Indian journalist, and founder and president of the Tamil Nadu Union of Journalists. He was also Vice President of All India Journalists.

D. S. Ravindra Doss

Born 20 November 1945

Died 22 June 2012 (aged 66)

Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Occupation newspaper editor, journalist

Career

Although journalism was the largest part of his career, Doss was also a writer, social activist, and political critic. He wrote more than 1,000 articles in different Tamil magazines and daily newspapers. He authored more than 15 books, mainly on social issues and Indian cinema. He was the editor and publisher of the monthly Tamil magazine Tamil Thendral, which was captioned as "A Magazine by Journalists for Journalists".

Dev Kumar

Dev Kumar (born February 6, 1972) is a prominent Dalit writer, dramatist, and theatre activist from India, specifically from Uttar Pradesh. He is widely recognized for his contributions to Dalit literature and theatre, focusing on raising awareness about caste oppression, social exclusion, and Dalit consciousness.

Background and Early Life

- Born in the Haddi Godam locality of Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh.

- He belongs to the Bhangi community (also known as Valmiki or Chuhra), which is classified as a Scheduled Caste (SC) under India's Constitution. This community has historically faced severe social discrimination, untouchability, and economic marginalization, often associated with traditional occupations like manual scavenging.

- His mother, Ganga Devi, worked as a maid-servant, reflecting the economically disadvantaged and low-class family background typical of many Dalit households in that era and region.

- Growing up in such circumstances shaped his perspective, leading him to use writing and theatre as tools for social change and empowerment.

Career and Contributions

- In April 1992 (notably on Ambedkar Jayanti, April 14 in some references), he founded Apna Theatre (meaning "Our Theatre") in Kanpur.

- The group performs street plays, proscenium theatre, and community-based productions primarily in Kanpur and surrounding areas of Uttar Pradesh.

- Its main objective is to arouse Dalit consciousness, challenge caste hierarchies, address stigma around manual labor/scavenging professions, and promote social justice through accessible, folk-inspired dramatic forms.

- Dev Kumar is both a playwright and director, using theatre to reach grassroots audiences where traditional literature might not penetrate.

Notable Works (Plays)

His popular and impactful plays include:

- Daastan (often spelled Dastaan)

- Bhadra Angulimaal (a reimagining or critique involving the Buddhist story of Angulimala, adapted to Dalit themes)

- Chakradhari

- Sudarshan Kapat (or Sudharshan Kapat)

- Jamadaar Ka Kurta (a play that directly confronts the stigma and lived realities of sanitation workers/jamaadars, drawing from his community's experiences)

These works blend mythological/historical references with contemporary Dalit struggles, often critiquing Brahmanical narratives while asserting Dalit agency and identity.

Recognition and Legacy

- He is featured in lists of influential Dalit writers and activists, such as in Youth Ki Awaaz's compilation of "36 Dalit Writers Who Disrupted India's Literary History" and various Dalit literature overviews.

- His biography appears on platforms like the Dalit Resource Centre (associated with biographical projects on marginalized writers) and Wikipedia.

- Through Apna Theatre, he has helped democratize theatre as a medium for Dalit resistance and education in northern India, especially in Uttar Pradesh.

- His efforts align with broader Dalit literary movements that emphasize self-representation ("Dalit life can only be truly understood by Dalits") and reject upper-caste pity or misrepresentation.

(Note: There are other individuals named Dev Kumar, such as the late Bollywood actor Dev Kumar (born Chaman Lal Kohli, 1930–1990), known for villain roles in films like Namak Halaal. But based on your previous questions about writers and the "- writer" specifier, this refers to the Dalit dramatist from Kanpur.)

In 2008, he co-founded and was the founding CEO of Bluefin Labs, a social TV analytics company, which MIT Technology Review named as one of the 50 most innovative companies of 2012. Bluefin was acquired by Twitter in 2013.

The rather long title could have been longer if it were to encapsulate the full range of the subjectivity of this scribe. It should have been "The dilemma of being an upwardly mobile, English speaking, Dalit Feminist and ideologue who is simultaneously a wannabe intellectual, a commodity fetishist and a person with ambivalent sexual orientation (I am deliberately choosing not to use the word "queer" since I am not sure what it means) and who is working in Kolkata, West Bengal".

The rather long title could have been longer if it were to encapsulate the full range of the subjectivity of this scribe. It should have been "The dilemma of being an upwardly mobile, English speaking, Dalit Feminist and ideologue who is simultaneously a wannabe intellectual, a commodity fetishist and a person with ambivalent sexual orientation (I am deliberately choosing not to use the word "queer" since I am not sure what it means) and who is working in Kolkata, West Bengal".In this context a Brahmin taxi driver or a Dalit lecturer or activist (especially) is an eyesore, a cause of moral and political anathema. This is feudalism twisted to suit the needs of Bhadrolok Radicalism. Bhadrolok Marxism entailed that a caste of people /bhadrolok will be destined to emancipate another caste of people, the chotolok. If the chotolok suddenly claims to be a Dalit and emancipates himself or herself then he/she challenges the bhadrolok's prerogative to liberate the chotolok thereby challenging a system of dependence, power and relationship of dominance and subordination. He/she is also laying a claim to a history of movement that has focused on the agency of Dalits and suspected the benevolence and the radicalism of the savarnas.

Dr. Dharamvir Bharati - writer

(25 December 1926 – 4 September 1997) was one of the most prominent and versatile figures in modern Hindi literature, known for his contributions as a poet, novelist, playwright, essayist, and social thinker. His work left an indelible mark on Indian literature, blending emotional depth, social commentary, and innovative storytelling. Below is a comprehensive overview of his life, career, literary contributions, and legacy, based on available information.

Early Life

- Birth and Family: Dharamvir Bharati was born on 25 December 1926 in the Atarsuiya neighborhood of Allahabad (now Prayagraj), Uttar Pradesh, India, into a Kayastha family. His father, Chiranjee Lal Verma, and mother, Chanda Devi, were part of a family influenced by the Arya Samaj movement, which instilled in him a sense of social reform and religious values. The family faced financial hardship after his father’s early death, leaving Bharati and his sister, Veerbala, to navigate challenging circumstances.

- Education: Despite economic difficulties, Bharati excelled academically. He completed his schooling at D.A.V. College in Allahabad and pursued higher education at Allahabad University, earning a B.A. and an M.A. in Hindi literature in 1946, securing the Chintamani Ghosh Award for topping his class. He later earned a Ph.D. in 1954 under Dr. Dhirendra Verma, with his thesis on "Siddha Sahitya," focusing on medieval Buddhist Vajrayana literary traditions.

Career

- Early Career: After completing his M.A., Bharati began working as a sub-editor for Hindi magazines Abhyudaya and Sangam in Allahabad. These roles honed his editorial skills and exposed him to the literary and journalistic landscape of the time. He later joined Allahabad University as a lecturer in Hindi, balancing teaching with his creative writing.

- Editor of Dharmayug: In 1960, Bharati moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) to become the chief editor of Dharmayug, a leading Hindi weekly magazine published by the Times Group. He served in this role until 1987, transforming Dharmayug into a cultural and literary institution that showcased contemporary Hindi literature, social issues, and intellectual discourse. His editorship significantly elevated the magazine’s influence and readership.

- Literary Contributions: Alongside his editorial work, Bharati prolifically wrote poems, novels, plays, essays, and short stories, addressing themes of love, human relationships, social issues, and existential dilemmas. His works are noted for their emotional resonance, psychological depth, and innovative narrative techniques.

Literary Works

Bharati’s oeuvre spans multiple genres, with several works considered landmarks in Hindi literature. Below are his major contributions:

Novels

- Gunaho Ka Devta (The God of Sins, 1949): This novel is regarded as a timeless classic in Hindi literature, exploring themes of love, sacrifice, and societal constraints. Set in Allahabad, it follows the emotional complexities of a young couple, Chander and Sudha, whose love is thwarted by social norms. Its lyrical prose and psychological insight have made it an evergreen work, widely read and adapted for stage and radio.

- Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda (The Seventh Horse of the Sun, 1952): This novel is celebrated for its experimental narrative structure, using a frame story where a narrator recounts seven love stories over seven afternoons. Its non-linear storytelling and philosophical undertones made it a unique contribution to Hindi fiction. The novel was adapted into a National Film Award-winning movie in 1992 by Shyam Benegal, further cementing its cultural significance.

Plays

- Andha Yug (The Age of Blindness, 1954): Bharati’s most famous play, Andha Yug, is a poetic drama set on the final day of the Mahabharata war. It explores themes of moral decay, human failure, and the consequences of war, using the epic’s characters as metaphors for contemporary society. The play has been widely performed by prominent Indian theatre directors like Ebrahim Alkazi, Ratan Thiyam, Arvind Gaur, and M.K. Raina, and is considered a masterpiece of modern Indian theatre.

- Other plays include Kanchanrang and Nadi Pyasi Thi, which also reflect his ability to blend poetic expression with social critique.

Poetry

Bharati was a gifted poet whose works addressed themes of love, human struggle, poverty, and resilience. Some notable poetry collections include:

- Kanupriya: A lyrical exploration of love, inspired by the Radha-Krishna motif, blending traditional and modern sensibilities.

- Thanda Loha: A collection reflecting social and personal struggles.

- Saat Geet Varsh: A set of poems showcasing his emotional and philosophical depth.

- Sapna Abhi Bhi, Yatra Chakra, Aadyant, and Pashyanti: Other poetry collections that highlight his versatility. His poetry is noted for its emotional intensity and ability to capture the human condition, as seen in selections featured by Amar Ujala Kavya, which praised his work for celebrating human creativity amidst adversity.

Other Works

- Short Stories and Essays: Bharati wrote numerous short stories and essays, often addressing social and psychological issues. His stories are known for their vivid portrayal of human emotions and societal challenges.

- Translations: He translated works like Oscar Wilde Ki Kahaniyan, showcasing his engagement with global literature.

- Siddha Sahitya: His Ph.D. research on Siddha literature resulted in a scholarly book, contributing to the study of medieval Hindi literary traditions.

Personal Life

- Marriages: Bharati married twice. His first marriage to Kanta Bharati in 1954 ended in divorce, and they had a daughter, Parmita. He later married Pushpa Bharati, with whom he had a son, Kinshuk Bharati, and a daughter, Pragya Bharati. His personal life, particularly his first marriage, was marked by emotional turmoil, which some sources suggest influenced his writing, especially Gunaho Ka Devta.

- Health and Death: Bharati suffered from heart-related issues for several years. He passed away on 4 September 1997 in Mumbai at the age of 70 due to a heart attack.

Awards and Recognition

Bharati’s contributions were widely recognized during his lifetime:

- Padma Shri (1972): Awarded by the Government of India for his literary achievements.

- Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1988): For playwriting, particularly for Andha Yug.

- Chintamani Ghosh Award: For academic excellence in Hindi during his M.A.

- Other accolades include various literary awards for his novels, plays, and poetry, reflecting his towering presence in Hindi literature.

Legacy

- Literary Influence: Bharati is considered one of the greatest litterateurs in Hindi literature, with works that remain relevant for their emotional depth, social commentary, and innovative forms. His novel Gunaho Ka Devta and play Andha Yug are staples in Hindi literature curricula, especially for students preparing for exams like UGC/NET.

- Cultural Contributions: His editorship of Dharmayug made it a platform for emerging writers and intellectual discourse, shaping Hindi journalism and literature. His works have inspired adaptations in film (Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda), theatre (Andha Yug), and radio.

- Social Thinker: Bharati’s writings often reflected his commitment to social reform, influenced by his Arya Samaj upbringing and his observations of India’s socio-political landscape during the colonial and post-independence eras.

- Continued Relevance: His works continue to be published and celebrated, with collections like Dharamveer Bharti Granthawali (a nine-volume set) preserving his legacy. His poetry and plays are frequently performed, and his novels remain popular among readers and scholars.

Notable Characteristics

- Versatility: Bharati’s ability to excel in multiple genres—poetry, novels, plays, essays, and journalism—set him apart as a polymath in Hindi literature.

- Innovative Storytelling: His use of experimental techniques, such as the non-linear narrative in Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda, was groundbreaking in Hindi fiction.

- Emotional and Social Depth: His works often explored the tension between individual desires and societal expectations, making them relatable across generations.

- Philosophical Undertones: Influenced by his research on Siddha literature and his Arya Samaj background, Bharati’s works often grapple with existential and moral questions.

इस अवसर पर यह दोहा याद आ रहा हैः-

सरस कविन के मम्म कौ, वेधत द्वै मो कौन।

असमझवार सराहिबौ, समझवार को मौन।

Contribution

Gahmari ji's vision of writing was very clear and settled.

The number of original detective novels of Gopalram Gahmari is 64. Even if we translate the translated novels, then it reaches close to 200.

Secret story