Anima Baa

Anima Baa is an Indian social activist, founder, and chief functionary of the Ashray South Vihar Welfare Society for Tribal (also known as SVWST or Ashray), a non-profit organization based in Jharkhand, India. She is dedicated to advocating for the rights and empowerment of tribal (Adivasi), vulnerable, and marginalized communities, with a strong focus on combating social discrimination, injustice, economic inequality, human trafficking, child and women's rights, education, health, nutrition, food security, agricultural development, natural resource management, and preservation of tribal identity and culture.

Background and Identity

- Origins and Community: Anima Baa hails from Jharkhand (formerly part of Bihar), a region with significant tribal populations facing systemic marginalization, land dispossession, poverty, and discrimination. While not explicitly classified as SC/ST in every source, her work centers on Scheduled Tribes (ST/Adivasi) communities, which are constitutionally recognized as disadvantaged and marginalized groups in India (similar to SC for Dalits but focused on indigenous/tribal peoples). She addresses caste-like hierarchies, social exclusion, and economic deprivation within tribal contexts, often highlighting how the existing system holds "diversity, rich culture, and traditional practices" while solving community problems internally when empowered.

- This aligns her activism with those from disadvantaged, historically marginalized, and low-status communities in India's social justice framework—particularly Adivasi/ST groups facing exclusion akin to (but distinct from) Dalit/SC experiences. Unlike purely Dalit-focused activists (e.g., Thenmozhi Soundararajan, Suraj Yengde, or Cynthia Stephen from prior discussions), her emphasis is on tribal rights, though intersections with caste discrimination in rural India are implicit in her critiques.

Education and Professional Journey

- She is described as a passionate social worker who founded Ashray with a group of young professionals motivated by the realities of injustice and inequality.

- Recipient of several awards and accolades for her contributions.

- Participant in the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP), a prestigious U.S. State Department exchange initiative for emerging global leaders.

Activism and Key Contributions

- Founding Ashray (1998): Established the South Vihar Welfare Society for Tribal (Ashray) in Ranchi/Jharkhand as a grassroots NGO. It began as a collective of committed individuals addressing the struggles of tribals and vulnerable groups through advocacy, capacity building, and community-led solutions.

- Core Focus Areas:

- Anti-human trafficking, child protection, and women's empowerment.

- Education, health & nutrition programs.

- Agricultural and livelihood support, natural resource management.

- Tribal rights, identity preservation, and cultural respect.

- Combating social discrimination and promoting internal community resolution mechanisms.

- Approach: Emphasizes empowering communities so they can solve their own issues, building second-line leadership, and fostering respect for tribal traditions amid modernization pressures.

- Public Engagements: Organizes events like International Yoga Day celebrations (e.g., 2019 in collaboration with local groups), participates in indigenous peoples' forums (e.g., Indigenous Knowledge and Peoples of Asia conferences), and engages in global networks (e.g., responses to calls for indigenous lands focus in 2020).

- Legal/Other Mentions: Involved in at least one documented legal proceeding (Anima Baa vs. State of Jharkhand, 2021, Jharkhand High Court—likely related to organizational or activist matters, though details are limited publicly).

Legacy and Recognition

Anima Baa represents dedicated, grassroots tribal advocacy in eastern India, where Adivasi communities face ongoing challenges from development projects, land grabs, and socioeconomic exclusion. Through Ashray, she has built an organization with departmental structure and leadership development, impacting vulnerable groups in Jharkhand and beyond. Her work promotes dignity, self-reliance, and cultural pride for tribals—making her a key figure in India's indigenous rights and social welfare movements.

Information on her is primarily from NGO profiles, CSR directories, organizational websites, and occasional news/social media mentions (e.g., Facebook pages for SVWST/Ashray). She maintains a lower public profile compared to transnational Dalit activists but is respected locally for her long-term commitment since the late 1990s. Her story highlights women-led change in tribal empowerment, emphasizing that community respect and internal strength are pathways to justice.

Abhina Aher

Early Life and Personal Journey

Abhina Aher was born as Abhijit Aher in a middle-class Marathi family in Mumbai’s Worli area. Her father passed away when she was three, leaving her mother, Mangala Aher, a trained Kathak dancer who worked for a government organization, to raise her single-handedly. Mangala later remarried. Abhina’s early exposure to her mother’s dance performances inspired her to emulate her, practicing in private and developing a passion for dance.

From a young age, Abhina experienced gender dysphoria, identifying with feminine traits and cross-dressing by age seven. Puberty brought challenges, as physical changes like facial hair and a deeper voice caused distress, leading her to avoid mirrors. She faced severe discrimination, including hate crimes at school, such as a traumatic incident of sexual violence involving a wooden ruler. Societal stigma and limited access to information about gender and sexuality in her youth compounded her struggles.

To cope and honor her mother’s wishes, Abhina initially tried to conform to societal expectations of masculinity during her college years, cutting her hair, wearing formal men’s clothing, and playing sports. She pursued a degree at Mumbai University and a diploma in software engineering. However, her encounter with Ashok Row Kavi, a journalist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, marked a turning point. Inspired, she abandoned her software career to join The Humsafar Trust, embarking on her lifelong activism journey.

Activism and Professional Contributions

Abhina Aher’s activism focuses on transgender rights, HIV/AIDS advocacy, and gender and sexuality inclusion. With over two decades of experience, she has worked with national and international organizations, addressing the needs of marginalized communities, including transgender people, men who have sex with men, sex workers, intravenous drug users, and people living with HIV. Her roles and contributions include:

Key Organizations and Roles:

- The Humsafar Trust (Mumbai): Abhina began her activism here, working on social projects to support the LGBTQ+ community and HIV/AIDS awareness.

- India HIV/AIDS Alliance: Since 2010, she has served as Associate Director for Gender, Sexuality, and Rights, managing programs like Pehchan, a Global Fund-supported initiative for transgender and MSM communities. She has also been a consultant on trans issues.

- I-TECH India: As a Technical Expert for Key Populations, Abhina works on health and human rights issues, leveraging her expertise in NGO management and social entrepreneurship.

- Family Health International (FHI) and Johns Hopkins University Centre for Communication Programmes (CCP): She contributed to health communication and program delivery for marginalized groups.

- Global Action for Trans Equality (GATE) and International Trans Fund (United States): Abhina serves as a consultant and steering committee member, advocating for trans rights globally.

- Asia Pacific Transgender Network (APTN): She was a board member from 2015 to 2018, working to increase transgender visibility and rights in the region.

- Women4GlobalFund and India Working Group (IWG): As a trans woman from the Hijra community, she advocates for increased domestic financing and global health grants.

Advocacy Work:

- HIV/AIDS and Health: Abhina has focused on reducing stigma and improving access to healthcare for HIV-positive transgender individuals and other marginalized groups. Her work includes community-based interventions, HIV testing campaigns, and addressing the unique needs of older adults living with HIV.

- Transgender Rights: She advocates for legal, social, and economic inclusion, challenging transphobia and promoting gender-neutral policies in workplaces and healthcare. Her efforts contributed to India’s 2014 Supreme Court ruling recognizing transgender rights.

- Public Speaking: A TEDx speaker in Delhi and Varanasi, Abhina shares her personal story and insights on gender inclusion, inspiring audiences to rethink societal biases.

- Pride Parades and Advocacy: She actively participates in pride parades and collaborates with organizations to promote transgender visibility and rights.

Founding Organizations

Abhina Aher has founded two significant initiatives to empower transgender individuals through art and advocacy:

- Dancing Queens (2009): A transgender-led dance group co-founded with Urmi Jadhav and Madhuri Sarode, Dancing Queens uses dance to break stereotypes, advocate for trans rights, and increase visibility. The group has performed across cities, including at Godrej India Culture Lab in Mumbai, blending traditional forms like Kathak with advocacy.

- TWEET Foundation (2016): The Transgender Welfare Equity and Empowerment Trust Foundation is India’s first organization led by trans men and women, focusing on empowerment, livelihoods, and rights. As Chief Executive, Abhina leads efforts to create opportunities and combat discrimination.

Challenges and Advocacy Through Personal Experiences

Abhina’s journey has been marked by significant personal and societal challenges, which she channels into her advocacy:

- Gender Dysphoria and Transition: Her decision to transition was emotionally complex, involving a two-hour conversation with her mother, who initially feared societal rejection but later joined the Sweekar Foundation, a group for parents of LGBTQ+ individuals, and Dancing Queens.

- Hate Crimes and Discrimination: Abhina endured violence and stigma, including being raped as an adolescent and facing societal rejection for her gender identity. She also engaged in sex work for survival, an experience she openly discusses to highlight systemic issues.

- Travel Incidents: Abhina has faced transphobia at airports, notably at Abu Dhabi in 2016, where security officials questioned her gender and refused to frisk her appropriately, leading to humiliation. She uses such experiences to advocate for sensitivity training and better policies.

Achievements and Recognition

- Global Activism: Abhina has been a global advocate for over 24 years, working with organizations like the International Trans Fund, APTN, and Women4GlobalFund. Her work on the Global Fund’s Replenishment and domestic financing advocacy highlights her influence.

- TEDx Speaker: Her talks in Delhi and Varanasi have amplified transgender voices and challenged societal norms.

- Media Presence: Abhina has been featured in outlets like BBC World Service, NDTV, and MagnaMags, sharing her story and advocating for change.

- Bond Conference 2019: She spoke at the opening keynote, discussing civil society’s role in inclusivity.

- Expertise: Recognized for her skills in NGO management, safeguarding, program delivery, and peer-to-peer service, Abhina is a sought-after consultant and leader.

Personal Philosophy and Impact

Abhina emphasizes the power of community engagement and education to change mindsets, stating, “Policies don’t change the mindset of the people. What changes the mindset is when people come together, try to understand the community and create a difference.” Her work with Dancing Queens and TWEET Foundation reflects her belief in using art and empowerment to challenge stereotypes and foster inclusion.

Her mother’s eventual acceptance and involvement in advocacy work highlight the personal impact of Abhina’s journey, inspiring others to embrace their identities and advocate for systemic change. By addressing issues like airport security protocols and workplace inclusion, she pushes for practical solutions to everyday discrimination.

Current Role and Contact

As of July 2025, Abhina serves as Chief Executive of the TWEET Foundation, leading transgender welfare initiatives. She is based in South Delhi and can be contacted at Abhina@tweetindia.org. Her LinkedIn profile reflects her extensive network and leadership in social development.

Critical Perspective

Adv. Rahul Singh

Adv. Rahul Singh (often referred to as Rahul Singh, @Kain_Rahul_S on X/Twitter) is an Indian human rights activist, Dalit rights defender, advocate (lawyer), and legal expert focused on combating caste-based discrimination, atrocities against Scheduled Castes (Dalits), and discrimination based on work and descent. He is associated with organizations and networks working on Dalit justice, atrocity monitoring, and promotion of rights for marginalized communities in India. His work emphasizes legal advocacy, monitoring of laws like the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, and building capacity for human rights defenders.

Professional Background

- Practicing advocate (lawyer) with expertise in human rights law, constitutional matters, and cases related to caste discrimination and atrocities.

- Known for his role in documenting, analyzing, and advocating against caste-based violence and systemic exclusion.

- Involved in producing resources for effective implementation of protective laws for Dalits.

Key Contributions & Work

- Authored or contributed to "A Handbook for Dalit Human Rights Defenders: For Effective Monitoring of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989" — a practical guide for activists, lawyers, and community leaders to track and report atrocities, ensure justice, and hold authorities accountable.

- Associated with initiatives like the Atrocity Tracking and Monitoring System (ATM) and networks such as the National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ) and Asia Dalit Rights Forum (ADRF), where he has been commended for dedication to Dalit rights.

- His efforts include legal support, awareness building, and advocacy for communities facing discrimination on grounds of work and descent (e.g., manual scavengers, certain occupational castes).

- Active on social media (X/Twitter @Kain_Rahul_S), where he positions himself as a "Rights Defender" and shares updates on Dalit issues, legal developments, human rights violations, and calls for protection of vulnerable groups.

Activism Focus

- Dalit rights & anti-atrocity work: Monitoring implementation of SC/ST (PoA) Act, supporting victims of caste violence, and pushing for better enforcement.

- Broader human rights: Addressing intersectional discrimination affecting Dalits and similar marginalized groups.

- He collaborates with civil society organizations to strengthen grassroots monitoring and legal interventions against caste oppression.

Public Presence

- Maintains an active profile on X (formerly Twitter) as @Kain_Rahul_S, describing his mission as the "Promotion & Protection of the rights of Dalits & communities discriminated on Work and Descent."

- Recognized in reports and acknowledgments from Dalit rights platforms for his contributions to justice mechanisms.

Note: "Rahul Singh" is a very common name in India, with many advocates sharing it (e.g., in Supreme Court, High Courts, or district levels). The activist profile matching "Adv. Rahul Singh" in the context of Dalit/human rights activism aligns most closely with the rights defender and handbook author described above. If this refers to a different individual (e.g., a specific regional activist or another advocate), additional details like location or specific cases would help narrow it down.

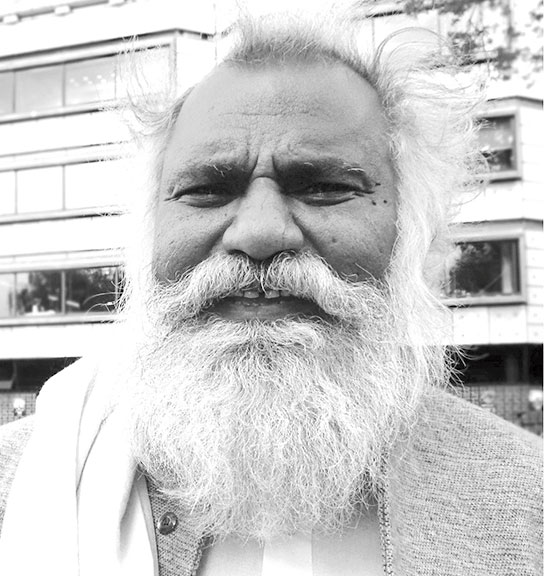

Mr. Amarjit Singh

Mr. Amarjit Singh is a long-standing Ambedkarite activist, anti-caste thinker, and anti-racist campaigner based in the United Kingdom (primarily London). He has been actively involved in anti-caste and anti-racist work for several decades, focusing on the rights of Dalits (formerly "Untouchables"), Adivasis (tribal communities), and other oppressed groups both in India and in the diaspora.

Background & Early Involvement

- Born in India (exact birth date and place not widely publicized in public profiles).

- Migrated to the UK, where he settled and became part of the South Asian diaspora community.

- Deeply influenced by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's philosophy of social justice, annihilation of caste, and rationalism.

- Adopted an Ambedkarite worldview — emphasizing the need to dismantle caste hierarchies, promote education, equality, and human rights for marginalized castes and communities.

Activism & Key Contributions

Amarjit Singh has campaigned consistently on behalf of India's Dalit and Adivasi communities, both in the UK and internationally. His work bridges caste oppression in India with diaspora experiences and broader anti-racist struggles.

- Anti-caste campaigning in the UK — For decades, he has advocated for recognition of caste discrimination as a form of racism affecting South Asian communities in Britain. He has highlighted how caste prejudice persists in diaspora settings (e.g., employment, marriage, social exclusion, and religious spaces).

- Humanistic perspective on caste — Delivered talks and writings viewing caste as a dehumanizing system that contradicts modern values of equality and dignity. He has spoken at humanist, secular, and anti-racist forums.

- Support for Dalit liberation — Contributed to discussions, book launches, and events promoting Ambedkarite literature and politics. Notably:

- Participated in the London launch and related discussions of Hatred in the Belly: Politics behind the Appropriation of Dr Ambedkar's Writings (2016), a critical Ambedkarite publication edited by Ashok Gopal and others.

- Engaged with anti-caste scholars and activists in critiquing attempts to dilute or appropriate Ambedkar's radical legacy.

- Anti-racist work — Connected caste oppression to broader racism, collaborating with anti-racist groups and emphasizing solidarity between oppressed communities.

- Writings & intellectual contributions —

- Contributed letters, articles, and commentary to Dalit publications like Dalit Voice (e.g., discussions on caste vs. class, critiques of Brahminical influences).

- Featured in reviews and discussions in journals and books on Dalit movements (e.g., review contributions in South Asia Research journal in the 1980s).

- Events & platforms — Spoke at university events (e.g., SOAS University of London), humanist societies (e.g., Farnham Humanist Society talk on caste in India and the UK), and Ambedkarite gatherings.

Public Presence & Recognition

- Known in Ambedkarite and Dalit diaspora circles in the UK and beyond.

- Respected as an honest intellectual and consistent voice against caste hierarchy, often praised in Dalit activist spaces for clarity and commitment.

- Maintains a low-key but enduring presence — not a high-profile media figure, but a respected grassroots thinker and campaigner.

Distinction from Other Figures

Note: There are several prominent individuals named Amarjit Singh or Dr. Amarjit Singh in the UK and diaspora activism, including Sikh/Khalistan-focused leaders (e.g., Dr. Amarjit Singh associated with Sikh Federation UK and TV84 appearances). The Ambedkarite anti-caste activist described here is a distinct individual focused on Dalit rights, caste annihilation, and anti-racism, not Sikh separatist politics.

Amarjit Singh's lifelong dedication reflects the global reach of Ambedkar's ideas — taking the fight against caste from India to the diaspora and framing it within universal human rights and anti-racist frameworks.

Ashok Bharti

Ashok Bharti (born 26 May 1960) is a prominent Indian Dalit rights activist, social entrepreneur, Ambedkarite leader, institution builder, and advocate for social justice. He is the Founder and Chairman of the National Confederation of Dalit and Adivasi Organisations (NACDAOR) (also referred to as NACDOR or National Confederation of Dalit Organisations), India's largest platform uniting Dalit and Adivasi groups for advocacy, empowerment, and policy influence. He is also the Chairman of the International Commission for Dalit Rights (ICDR) in the US and holds positions like Kabir Chair on Social Conflict at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS). An Ashoka Fellow (elected 2005), he has over 40 years of experience in grassroots organizing, national movements, and international advocacy for Dalit emancipation, inclusion, and human rights.

Early Life & Background

- Born on 26 May 1960 in an extremely poor Dalit family in Basti Rajaram, a slum for "untouchables" near Jama Masjid in old Delhi.

- One of seven children; his grandfather cut grass for fodder, father was a tailor, and mother made paper bags to supplement income.

- Despite extreme poverty and caste discrimination, his parents prioritized education; Ashok studied on merit at Hindu College (Delhi University) and then earned an engineering degree from the prestigious Delhi College of Engineering (now Delhi Technological University).

- Grew up with firsthand experience of Dalit vulnerabilities, shaping his lifelong commitment to upliftment.

Activism & Political Journey

- Began activism in the 1980s as a student leader, deeply influenced by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's teachings on equality, rationalism, and annihilation of caste.

- At age 18, organized a successful student strike to secure a promised building for his school.

- Founded Mukti (Freedom), a student organization that reformed university admission processes.

- Disillusioned by aspects of the Mandal Commission agitations (late 1980s), he shifted focus to alternative Dalit narratives.

- In 1995, founded the Centre for Alternative Dalit Media (CADAM), which organized India's first Dalit Women's Conference and laid groundwork for broader platforms.

- This evolved into the National Conference of Dalit Organizations (later NACDOR/NACDAOR in expanded form), a confederation of thousands of Dalit and Adivasi groups across India.

- As Chairman of NACDAOR, he leads nationwide campaigns for:

- Social justice, economic inclusion, and anti-discrimination policies.

- Better budget allocations for SC/ST/OBC/minorities (critiquing Union Budgets as inadequate or "jokes" on marginalized populations).

- Addressing insecurity among Dalits (e.g., in Bihar, highlighting failures in protection even for high-profile figures like judges or IPS officers).

- Critiquing political shifts (e.g., why Dalits deserted BJP in certain elections due to unfulfilled promises).

- Internationally: Co-Chair of Indigenous People International Action Team (Brussels); Convenor of Global Task Force on Social Exclusion (Global Call to Action Against Poverty); early leader in World Social Forum; representative for Asia in global Dalit rights networks.

Key Roles & Affiliations

- Chairman, National Confederation of Dalit & Adivasi Organisations (NACDAOR).

- Chairman, International Commission for Dalit Rights (ICDR), US (founding board chair until 2011).

- Kabir Chair on Social Conflict, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS).

- Member, Working Groups on Dalits, National Advisory Council (Government of India, during UPA era).

- Advisory board roles (e.g., FPACL).

- Frequent commentator on TV, media, and forums (e.g., interviews on Dalit issues, budgets, caste violence).

Awards & Recognitions

- Ashoka Fellowship (2005) for innovative social entrepreneurship in Dalit rights.

- Dalit Ratna Award.

- CARE Millennium Award (2011) for outstanding work on Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), from CARE Deutschland-Luxemburg.

- Lifetime Achievement Award at National Dalit forums.

- Recognized as a nationally and internationally renowned Dalit leader, ideologue, and institution builder.

Views & Legacy

Ashok Bharti emphasizes inclusive democracy, critiquing exclusion in systems like budgets, politics, and society. He advocates for Dalits and Adivasis as central to India's progress, pushing for dignity, economic empowerment, and protection from violence. His work bridges grassroots mobilization with policy advocacy, making NACDAOR a powerful voice for marginalized communities.

He remains active (as of 2025–2026 reports), commenting on current events like caste insecurity in states, political alliances, and government policies.

Aasim Bihari

Maulana Ali Hussain 'Aasim Bihari' (also written as Maulana Ali Husain Aasim Bihari or Maulvi Aasim Bihari; born Ali Hussain around 1890–1895 – died after 1947, exact date uncertain) was an Indian Muslim Dalit activist, social reformer, religious scholar (maulvi), writer, poet, and anti-caste campaigner from Bihar. He is remembered as one of the most prominent Dalit Muslim voices in pre- and early post-independence India, particularly among the Muslim Pasmanda (backward/oppressed Muslim communities) and Dalit converts to Islam in Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh.

He belonged to the Ansari (Momin Ansari / Julaha) community — traditionally Muslim weavers classified as Pasmanda (backward Muslims) and often treated as socially inferior within South Asian Muslim society, facing caste-like discrimination similar to Hindu Dalits.

Early Life and Background

- Born in a poor Muslim weaver (Julaha/Ansari) family in Bihar (likely in the Patna, Gaya, or Muzaffarpur region; exact village not consistently documented).

- Came from a background of extreme poverty, social marginalization, and caste-like hierarchy within Muslim society (Pasmanda Muslims were often excluded from elite ashraf Muslim circles).

- Received traditional madrasa education and became a maulvi (Islamic scholar), but was deeply influenced by both Islamic egalitarianism and anti-caste ideas from the broader Indian freedom and social reform movements.

- Adopted the pen name 'Aasim Bihari' (meaning "protector of Bihar" or "defender of Bihar") to reflect his lifelong commitment to defending the oppressed people of Bihar.

Activism and Key Contributions

Maulana Aasim Bihari was active mainly in the 1920s–1940s, focusing on:

- Dalit-Muslim Unity and Pasmanda Assertion:

- Strongly advocated for the rights of Pasmanda Muslims (backward/oppressed Muslim castes such as Ansari, Qureshi, Rayeen, Dhunia, etc.) who faced discrimination from ashraf (upper-caste) Muslims.

- Argued that caste-like hierarchies existed within Indian Islam and needed to be dismantled — a radical position in his time.

- Promoted unity between Hindu Dalits and Muslim Pasmanda communities against common upper-caste/elite oppression.

- Anti-Untouchability and Social Reform:

- Campaigned against untouchability and social exclusion practiced against Dalit converts to Islam.

- Worked to end practices like separate burial grounds, denial of mosque entry, and social boycott of lower-caste Muslims.

- Emphasized the true egalitarian teachings of Islam and Prophet Muhammad to counter caste-based discrimination within the community.

- Freedom Struggle and Anti-Colonial Stance:

- Participated in the broader Indian independence movement but criticized both Congress and Muslim League for neglecting the rights of oppressed Muslims and Dalits.

- Supported composite nationalism and opposed the two-nation theory when it ignored the plight of Pasmanda Muslims.

- Literary and Journalistic Work:

- Published several books and pamphlets in Urdu on Pasmanda rights, Islamic egalitarianism, and social reform.

- Edited or contributed to Urdu periodicals and journals advocating Pasmanda and Dalit-Muslim causes.

- His writings were sharp, polemical, and aimed at awakening backward Muslims and Dalits to their rights.

Political and Organizational Role

- Associated with early Pasmanda Muslim movements in Bihar (predecessors to modern Pasmanda organizations like All India Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz).

- Linked with All India Depressed Classes organizations and Ambedkarite circles in the 1930s–1940s.

- Supported demands for separate electorates or reserved representation for Pasmanda Muslims and Dalits in legislatures.

- After independence (1947), continued advocating for Pasmanda rights within the new India.

Death and Legacy

- Exact date of death is not consistently recorded; he lived at least into the late 1940s or early 1950s.

- Remembered in Pasmanda Muslim and Dalit Muslim histories in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

- His name appears in academic studies on Pasmanda politics (e.g., works by Ali Anwar Ansari, Masood Alam Falahi, and others).

- Regarded as a pioneer of Pasmanda Muslim assertion — a movement that has gained renewed attention in 21st-century India (e.g., through leaders like Ali Anwar and organizations like AIMIM in some contexts).

- Symbolizes the early 20th-century struggle of Dalit Muslims who faced dual discrimination: as Muslims in a Hindu-majority society and as backward castes within Muslim society.

1. Early Life in Slavery

- Born enslaved on November 7, 1746, on a plantation in Sussex County, Delaware, owned by Abraham Wynkoop, a wealthy Anglican planter.

- Mother: unknown name; father: possibly named “Tom.”

- At age 16 (1762), his owner sold his mother, six siblings, and the plantation. Absalom was kept and moved to Philadelphia to work in Benjamin Wynkoop’s store on High (now Market) Street.

- Taught himself to read and write using the Bible, spellers, and any books he could find.

- Attended a night school for Black people run by Quakers (Society of Friends).

2. Path to Freedom

- 1770: Married Mary King (c. 1748–1824), an enslaved woman owned by a neighbor, Sarah King.

- Worked extra jobs and saved money to purchase his wife’s freedom first (October 4, 1778) so their children would be born free.

- Continued saving until October 1, 1784, when Benjamin Wynkoop signed his manumission papers—Absalom was 38 years old.

- Took the surname “Jones” after freedom.

3. Religious Awakening and Leadership

- 1780s: Became a lay preacher at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church (mixed-race congregation).

- 1787: With Richard Allen, founded the Free African Society—the first Black mutual-aid society in America. Provided sickness/death benefits, education, and anti-slavery advocacy.

- November 12, 1787: Famous incident at St. George’s—ushers tried to remove Black members (including Jones and Allen) from new seats to the balcony. They walked out and never returned.

4. Founding the African Church

- 1792: Purchased land at 5th & Adelphi (now St. James Place) in Philadelphia.

- July 17, 1794: Dedicated the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas—the first Black Episcopal congregation in the U.S.

- Chose the Episcopal Church because it had no racial restrictions on ordination and offered structure.

- 1802: Ordained deacon; 1804: Ordained priest by Bishop William White—becoming the first African-American priest in the Episcopal Church.

5. Major Activism & Abolition Work

- 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic: When white Philadelphians fled, Jones and Richard Allen organized Black nurses and burial teams. They saved countless lives but were falsely accused by publisher Mathew Carey of price-gouging. Jones and Allen published “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia” (1794)—the first copyrighted pamphlet by African Americans.

- 1795–1816: Led annual Thanksgiving Day petitions to Congress calling for abolition and an end to the slave trade.

- January 1, 1808: Delivered a famous sermon celebrating the U.S. ban on the international slave trade, declaring: “Let the first of January, the day of the abolition of the slave trade, be set apart… as a day of public thanksgiving.”

- 1816: Helped found the Society for the Suppression of the Slave Trade.

6. Community Building & Education

- Established schools for Black children at St. Thomas.

- Founded beneficial societies for widows and orphans.

- Advocated for Black masons, carpenters, and sailors to form guilds.

- 1810: Helped establish the African Masonic Lodge No. 459 (first Black Masonic lodge in Pennsylvania).

7. Family Life

- Wife: Mary King Jones (freed 1778; died 1824).

- Children: 6 survived to adulthood (Absalom Jr., John, Sarah, Mary, Rachel, and another daughter).

- Lived modestly in a house on Spruce Street near St. Thomas Church.

8. Death and Legacy

- Died February 13, 1818, of “lung fever” (likely tuberculosis or pneumonia).

- Funeral at St. Thomas was attended by thousands—Black and white.

- Buried in the churchyard of St. Thomas (later moved inside the church in 1870).

- February 13 is now his official feast day in the Episcopal Church (Lesser Feasts and Fasts).

- Stained-glass windows, schools, and streets named in his honor (e.g., Absalom Jones Episcopal Center in Atlanta).

9. Famous Quotes

- “God is no respecter of persons… He hath made of one blood all nations of men.”

- “If we ever hope to see a better day in this country, we must educate our children.”

10. Modern Recognition

- 1976: Included in Holy Women, Holy Men (Episcopal liturgical calendar).

- 1993: U.S. Postal Service issued a Black Heritage stamp with Absalom Jones and Richard Allen.

- 2023: Featured in the PBS documentary “The Black Church” by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Summary: Absalom Jones rose from chattel slavery to become America’s first Black Episcopal priest, co-founder of the independent Black church movement, and a fearless abolitionist who used faith, education, and community organizing to fight racism and uplift the most disadvantaged African Americans in the new republic. He is rightly called “The Black Bishop” and a father of Black liberation theology.

Anand Teltumbde

Anand Teltumbde (born 15 July 1951) is a prominent Indian scholar, writer, public intellectual, civil rights activist, and Dalit rights advocate. A leading voice in contemporary Indian leftist and Ambedkarite thought, he combines Marxist analysis with anti-caste perspectives to critique caste oppression, neoliberalism, Hindutva politics, and state repression. At age 74 (as of 2025–2026), he is a professor of management (specializing in Big Data) at the Goa Institute of Management and remains an influential commentator despite ongoing legal restrictions from his high-profile arrest in the Bhima Koregaon case.

Early Life & Education

- Born on 15 July 1951 in Rajur village, Yavatmal district, Maharashtra (then Bombay State), to a poor family of Dalit (Scheduled Caste) farm labourers.

- Grew up facing caste discrimination in rural Maharashtra; his family endured poverty and social exclusion typical of landless Dalit labourers.

- Overcame barriers through merit: Earned a B.E. in Mechanical Engineering from Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology (VNIT), Nagpur (1973).

- Completed an MBA from the prestigious Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (IIM-A, 1982).

- Obtained a PhD from the University of Mumbai (1993) in cybernetic modelling while working as an executive.

- Later awarded an honorary D.Litt. from Karnataka State Open University.

Professional Career

- Had a successful corporate career: Held senior executive roles at Bharat Petroleum and served as Managing Director & CEO of Petronet LNG.

- Transitioned to academia: Currently a professor at Goa Institute of Management, heading programs in Big Data and management.

- His professional success contrasts with his activist roots, allowing him to bridge corporate, academic, and activist worlds.

Activism & Advocacy

- Long-standing civil rights activist (over 40+ years), focusing on Dalit emancipation, human rights, anti-caste struggles, and protection of democratic rights.

- General Secretary of the Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights (CPDR).

- Associated with the All India Forum for Rights to Education (AIFRTE) (Presidium member) and other people's movements.

- Writes extensively on caste, class, Hindutva, neoliberalism, and state violence; regular contributor to Economic & Political Weekly, Frontline, The Wire, Scroll, Outlook, The Caravan, Indian Express, The Hindu, and Marathi/English outlets.

- Combines Ambedkarite anti-caste radicalism with Marxist class analysis; critiques both caste hierarchies and capitalist exploitation.

- Co-edited The Radical in Ambedkar (2018) and authored influential works on Dalit history and contemporary issues.

Key Books & Writings

Prolific author of over 30–33 books (many translated into Indian languages):

- Khairlanji: A Strange and Bitter Crop (2008) — on the 2006 caste atrocity murders.

- The Persistence of Caste: The Khairlanji Murders and India’s Hidden Apartheid (2010).

- Republic of Caste: Thinking Equality in the Time of Neoliberal Hindutva (2018).

- Dalits: Past, Present and Future (2016).

- Mahad: The Making of the First Dalit Revolt (2016).

- Iconoclast: A Reflective Biography of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar (2024).

- The Cell and the Soul: A Prison Memoir (2025) — detailing his 31 months in jail.

- Recent prolific output: Six books published since October 2024 (as of early 2026), including works on caste census and prison experiences.

Bhima Koregaon Case & Imprisonment

- Implicated in the Elgar Parishad–Bhima Koregaon case (2018): Accused under UAPA of Maoist links, inciting violence at the 2018 Bhima Koregaon commemorations, and plotting against the state (charges he denies as fabricated).

- Home raided in 2018; arrested on 14 April 2020 (Ambedkar Jayanti) after Supreme Court rejected anticipatory bail; surrendered to NIA.

- Spent 31 months in Taloja Central Jail (Navi Mumbai) under harsh conditions (including COVID risks).

- Released on bail in November 2022 (Bombay High Court granted, upheld by Supreme Court; stayed briefly then enforced).

- Case status (as of 2026): Out on bail with restrictions (e.g., cannot leave Maharashtra without court permission; trial ongoing, no conviction).

- Described post-release life as moving from a "small jail to a bigger jail" due to curbs on movement and social stigma.

Recent Events (2025–2026)

- Prolific writing continues despite restrictions.

- In February 2026, Mumbai Police directed cancellation of his book discussion (The Cell and the Soul) at Kala Ghoda Arts Festival (citing safety/permissions); event scrapped amid online backlash from right-wing accounts.

- Court permissions for travel (e.g., Kochi lit fest, family events) often denied or revoked, highlighting ongoing constraints.

- Remains a vocal critic of caste policies, state overreach, and democratic erosion.

Legacy & Views

Teltumbde is celebrated as a trenchant critic of caste violence, Hindutva, and neoliberalism; supporters view his arrest as state suppression of dissent. He has been called a "leading public intellectual" and compared to global figures for his sharp analysis. His work emphasizes that true equality requires annihilating caste alongside class structures.

He lives in Mumbai/Goa under bail conditions; his writings and activism continue to influence Dalit, leftist, and civil rights circles.

Arige Ramaswamy

Arige Ramaswamy (also spelled Arigay Ramaswamy or Arige Ramaswamy; 1885 – 23 January 1973) was a pioneering Indian Dalit social reformer, activist, writer, poet, and political leader from Hyderabad (then in the princely state of Hyderabad, now Telangana). He is regarded as one of the key figures in the early Adi-Hindu/Adi-Andhra movement in the Telugu-speaking regions, working tirelessly to unite Dalits (particularly Madigas and Malas), combat caste discrimination, abolish exploitative practices like the Devadasi/Jogini system, and promote self-respect, education, and socio-economic upliftment among marginalized communities. Often described as part of the "Trinity" or "triumvirate" of Dalit leadership in Hyderabad alongside Bhagya Reddy Varma and B.S. Venkat Rao, he played a crucial role in organizing Dalits in the early 20th century under Nizam rule.

Early Life and Background

- Born in 1885 in Secunderabad (or Hyderabad region), Andhra Pradesh (then Hyderabad State under Nizam rule).

- Came from a Dalit background (likely Madiga community, as his activism focused heavily on Madigas).

- Grew up amid severe caste oppression, untouchability, and socio-economic backwardness typical of Dalits in princely Hyderabad, where feudal structures and caste hierarchies intersected with religious and cultural norms.

- Limited formal education but self-taught and influenced by reformist ideas, including Vaishnavism, Achala philosophy, Brahma Samaj thought, and early anti-caste assertions.

Activism and Key Contributions

Arige Ramaswamy's work focused on uniting fractured Dalit sub-castes (e.g., Madigas and Malas), eradicating superstitions, and building community institutions:

- Organizations Founded:

- Suneeta Bala Samajam (in Secunderabad) – For children's welfare and education among Dalits.

- Matangi Mahasabha (in Nampalli) – To promote cultural and social reforms.

- Adi Hindu Jateeya Sabha (1922) – Co-founded with leaders like J. Papayya (vice-president) and Konda Venkataswamy (president); aimed at reforms among "Adi Hindus" (original inhabitants claiming pre-Aryan identity), including anti-superstition drives and Devadasi abolition.

- Arundhatiya Maha Sabha – To raise awareness and unity among Madigas (Arundhatiya is a term linked to Madiga identity).

- Major Campaigns:

- Fought against superstitions, animal sacrifices, child marriages, and alcoholism (seen as reinforcing debt, poverty, and disease in Dalit communities).

- Advocated for the abolition of the Jogini/Devadasi system (where lower-caste women were dedicated to temples as ritual prostitutes).

- Performed an inter-sub-caste marriage: Rescued a Mala girl from being dedicated as Jogini and married her to a Madiga boy under his supervision—symbolic act to foster unity between Malas and Madigas (often divided by sub-caste hierarchies).

- Promoted inter-caste dining, self-respect, and socio-medical reforms (e.g., anti-alcoholism campaigns in Telugu print media to break cycles of exploitation).

- Literary Contributions:

- Poet and writer; his works (e.g., poem 'Self-Respect of Savarnas' in Telugu Dalit anthologies) critiqued upper-caste hypocrisy and emphasized Dalit dignity.

- Contributed to Telugu Dalit literature, addressing themes of debt, oppression, and self-assertion.

- Political and Broader Role:

- Worked closely with Bhagya Reddy Varma (Adi-Hindu leader), B.S. Venkat Rao (Adi-Hindu Mahasabha General Secretary), and others in the Adi-Hindu Social Service League.

- Part of efforts leading to official recognition: Nizam's government adopted "Adi Hindu" in the 1931 census; influenced removal of derogatory terms for Dalits in records.

- Involved in broader Dalit self-respect movements in Hyderabad Deccan, blending religious reform (e.g., Brahma Samaj influences) with caste abolition.

Later Life and Death

- Remained active into old age, continuing advocacy for Dalit unity and reforms.

- Died on 23 January 1973 in Hyderabad, at age 88.

Legacy

Early Life and Personal Details

- Born: 15 March 1973 (age 52 as of 2025) in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India.

- She hails from the Kanpur region and has been active in politics primarily in constituencies around Kanpur Nagar district.

Political Career

Aruna Kori began her political journey with the Samajwadi Party (SP), a major regional party in Uttar Pradesh founded by Mulayam Singh Yadav.

- She was elected as a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from the Bilhaur constituency (Kanpur Nagar district) during the 2012 Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly elections on a Samajwadi Party ticket.

- In the Akhilesh Yadav government (2012–2017), she served as a Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Women Welfare (often referred to as Women and Child Development) and Culture from 15 March 2012 to 19 March 2017.

- Notably, she is recognized as the first woman to hold the position of Uttar Pradesh Minister for Women and Child Development.

She was the lone woman minister in the Akhilesh Yadav cabinet at the time of her swearing-in.

Prior to 2012, she also served as MLA from Bhognipur constituency (2002–2007), though details on her party affiliation during that term align with her SP background.

Party Changes and Later Activities

- She was associated with the Samajwadi Party until around 2019.

- Later, she joined the Pragatisheel Samajwadi Party (Lohiya) (also referred to as Pragatishil Samajwadi Party Lohia), a splinter or allied group in the socialist tradition.

- In 2019, she contested the Lok Sabha elections from the Misrikh constituency (Uttar Pradesh) as a candidate of Pragatishil Samajwadi Party (Lohia).

- She has also been linked to other electoral attempts, such as from Rasulabad in assembly contexts.

Some sources and her social media (e.g., Facebook pages) have referenced affiliations or descriptions like "Aruna Kori BJP" or updates on her roles as former MLA and minister, but her primary documented career is with Samajwadi Party and its offshoots.

Notable Incidents and Public Statements

In 2015, as Women and Child Welfare Minister, she faced criticism for stating that society (rather than the government) bore primary responsibility for incidents of rape, drawing flak from various quarters amid discussions on women's safety in Uttar Pradesh.

Other Notes

- Her name sometimes appears as Aruna Kumari Kori or Arun Kumari Kori in election affidavits and records (e.g., due to clerical entries during oath-taking), but she has clarified her correct name as Aruna Kori.

- She is active in social work alongside politics, focusing on women's issues, child welfare, and cultural matters, consistent with her ministerial portfolio.

Aruna Kori remains a notable figure in Uttar Pradesh politics, particularly for breaking barriers as a woman minister in a key department and her representation of reserved or general constituencies in the Kanpur belt. For the most current updates on her activities, checking recent election portals or her social media would be useful, as political alignments can shift.

Amit Jethwa

Background & Early Activism

Born: 31 December 1975, in Kodki village, Gir Somnath district, Gujarat.

Education: Law graduate.

Affiliations: President of the Gir Nature Youth Club and a vocal member of the Bishnoi community, a Hindu sect known for its strong environmental conservation ethos.

Core Cause: Protection of the Gir Forest—the last refuge of the Asiatic lion—from rampant illegal limestone mining in its periphery, which was destroying the ecosystem and wildlife corridors.

Key Battle & The RTI Weapon

The Target: Jethwa alleged that powerful politicians, including Dinu Bogha Solanki (then a BJP MP from Junagadh), were behind the illegal mining mafia operating in the Gir sanctuary area.

The Action: Instead of just protesting, he systematically used the Right to Information Act, 2005. He filed numerous RTI applications with the Gujarat High Court and the Forest Department to expose the illegal mining and the complicity of authorities.

The Lawsuit: His most significant act was filing a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Gujarat High Court in 2010, specifically naming MP Dinu Bogha Solanki. The PIL sought a CBI investigation into the illegal mining and the alleged role of Solanki.

Assassination & Immediate Aftermath

Date: July 20, 2010.

Location: Shot at point-blank range outside the Gujarat High Court in Ahmedabad, a symbolically significant location representing the law he was using.

The Attack: Two assailants on a motorcycle shot him. He succumbed to his injuries. The brazenness of the attack, in the heart of the legal precinct, sent shockwaves across the nation.

Immediate Accusations: Jethwa's father, Bhikhabhai Jethwa, and the activist community immediately accused MP Dinu Bogha Solanki of orchestrating the murder to silence the PIL. Solanki denied all allegations.

The Long Road to Justice – A Twisted Legal Saga

The investigation and trial became a marathon, fraught with allegations of political interference and witness intimidation.

Initial Investigation: The Ahmedabad Police Crime Branch gave a clean chit to Solanki. This was widely criticized.

CBI Takeover: Following sustained pressure from Jethwa's father and the Supreme Court's intervention, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) took over the case in 2013.

CBI Chargesheet: The CBI named Dinu Solanki as the main conspirator, alleging he hired killers for ₹5 lakh to eliminate Jethwa. Several others, including his nephew Shiva Solanki and sharpshooter Shailesh Pandya, were also charged.

Trial & Conviction (2019): In a landmark verdict in July 2019, a Special CBI Court in Ahmedabad convicted Dinu Bogha Solanki for murder and criminal conspiracy. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. Six others were also convicted.

High Court Acquittal (2024): In a dramatic turn, the Gujarat High Court acquitted Dinu Solanki and the six others in February 2024. The court cited lapses in the CBI investigation, doubtful witness testimonies, and lack of conclusive evidence linking Solanki to the shooters.

Current Status: The CBI has filed an appeal against the acquittal in the Supreme Court of India. The legal battle continues as of late 2024.

Legacy & Impact

Amit Jethwa's life and death left a deep impact:

Martyr for Environmentalism: He is remembered as a martyr for the cause of wildlife conservation, especially for the Gir lions.

Symbol of Activist Risks: His murder highlighted the extreme dangers faced by whistleblowers and activists challenging the powerful "nexus" of politicians, business, and crime.

RTI as a Tool: He exemplified the power of RTI as a weapon for citizens to fight corruption and environmental degradation.

Persistent Father: His father, Bhikhabhai Jethwa, became a symbol of a relentless pursuit for justice, fighting the case for over a decade despite threats and obstacles.

Unending Fight: The recent acquittal and the ongoing appeal underscore the immense difficulty in securing justice in cases where activists are killed for their work.

Annabhau Sathe

Annabhau Sathe (full name Tukaram Bhaurao Sathe; popularly known as Anna Bhau Sathe or Lokshahir Annabhau Sathe; 1 August 1920 – 18 July 1969) was a pioneering Indian social reformer, folk poet (Lokshahir), novelist, playwright, Dalit writer, and Marxist activist from Maharashtra. Born into the Matang (Mang) community — a Dalit (untouchable) caste traditionally associated with occupations like basket-weaving and often subjected to extreme social exclusion — he is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern Dalit literature in Marathi. His prolific writings (over 32 novels, 22 short story collections, 10 folk plays, powadas/ballads, and more) vividly portrayed the exploitation, poverty, caste oppression, and struggles of Dalits, workers, and the rural/urban poor. Influenced by Marxism and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's teachings, he blended class struggle with anti-caste activism, using art as a weapon for social change.

Early Life & Background

- Born on 1 August 1920 in Wategaon village, Valva tehsil, Sangli district (then Bombay Presidency; some sources note nearby Satara links), Maharashtra.

- From a poor Matang family: Father Bhaurao (or Bhau), mother Valubai; siblings included elder sister Bhagubai, brothers Shankar and Madhukar, and younger sister Jaibai.

- Faced severe caste discrimination from childhood — humiliated in school (rusticated or dropped out around 4th standard due to abuse), lived in segregated Mangwada outside villages.

- Extreme poverty forced his family to migrate on foot to Mumbai in 1931 (a grueling 6-month journey).

- In Mumbai, worked menial jobs: porter, shoe polisher, daily wage labourer, mill worker — experiences that shaped his proletarian worldview.

- No formal higher education; self-taught through observation, reading, and immersion in labour movements.

Activism & Political Journey

- Joined the freedom struggle early; influenced by Gandhian ideals initially but shifted to revolutionary socialism.

- Became a full-time Communist Party of India (CPI) worker in the 1940s; member of CPI.

- Co-founded Lal Bawta Kalapathak (Red Flag Cultural Troupe) in 1944 — a performing arts group using folk forms (powadas, songs, plays) to propagate communist ideology, raise class consciousness, and fight caste oppression.

- Key role in Samyukta Maharashtra Movement (1950s–1960) for a united Marathi-speaking state (formed 1 May 1960); earned titles like "Samyukta Maharashtra Janak" and "Shilpkar."

- Participated in Goa Freedom Movement and anti-colonial/anti-feudal struggles.

- Founded the first Dalit Sahitya Sammelan (Dalit Literary Conference) in Bombay (Mumbai) in 1958 — a landmark event; in his inaugural speech: "The earth is not balanced on the snake's head but on the strength of Dalit and working-class people."

- Followed Ambedkar's anti-caste vision but emphasized Marxist class analysis over Buddhism (unlike many contemporaries).

- Advocated for Dalit-working class unity, dignity, and rebellion against feudal/caste bondage.

Literary Works & Contributions

Sathe was extraordinarily prolific (active 1942–1969), writing in accessible Marathi folk styles while depicting raw realities of Dalit life.

- Novels (32+): Landmark Fakira (1959) — story of a Dalit protagonist's rebellion against feudal exploitation; won Maharashtra State Award (1961); reached 19 editions.

- Short stories (22 collections), folk plays (10), powadas/ballads (10), plays (2), travelogues, and urban literature.

- Themes: Caste atrocities, labour exploitation, rural-urban migration, poverty, resistance; semi-autobiographical elements.

- Credited with pioneering Dalit literature — predating the 1960s–70s Dalit Sahitya movement; influenced writers like Baburao Bagul, Namdeo Dhasal, Daya Pawar.

- Used all art forms (literature, theatre, songs) for awakening; beauty in versatility noted by scholars like Gail Omvedt.

Personal Life & Death

- Lived in poverty throughout; resided in Ghatkopar slum in later years.

- Government allotted a modest house in Mumbai suburbs ~1968.

- Died on 18 July 1969 at age 48–49 in Bombay (Mumbai), in destitution despite his contributions — born poor, died poor, largely ignored by mainstream society/literary circles during lifetime.

Legacy & Recognition

- Posthumous honors: India Post issued a commemorative stamp (1 August 2002).

- Titles: Sahitya-Samrat, Lokshahir, Sahityaratn, Jahadvikhyat, Dinjanancha Sfurtidata.

- Regarded as a revolutionary poet/novelist/playwright; organic intellectual of the oppressed.

- Influence: Continues to inspire Dalit-Marxist activism; recent biographies (e.g., 2024) highlight his enduring presence in Maharashtra's socio-cultural life.

- His work remains relevant for highlighting caste-class intersections and the power of art in resistance.

Annabhau Sathe's life and writings embody the fusion of Ambedkarite anti-caste zeal with Marxist class struggle — a voice for the margins that challenged both feudalism and untouchability through powerful, people-centered art.

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is a world-renowned American political activist, scholar, author, and public intellectual, primarily known for her work in Black liberation, prison abolition, feminism, and anti-capitalism. Her life and activism span over six decades and remain central to global struggles for justice.

1. Early Life

Born: January 26, 1944 (age 82), Birmingham, Alabama, United States

Spouse: Hilton Braithwaite(m. 1980-1983)

Partner: Gina Dent

Parents: Sallye Bell Davis, Benjamin Frank Davis, Sr.

Education: University of California, San Diego, Brandeis University, Humboldt University of Berlin, Goethe University Frankfurt, Little Red School House

Family Background: Her family lived in a racially mixed neighborhood called “Dynamite Hill” due to frequent Ku Klux Klan bombings targeting Black families. Her mother, Sallye Bell Davis, was a teacher and an active member of the Southern Negro Youth Congress (a communist-affiliated civil rights group), which deeply influenced Davis’s political awakening.

Education:

Attended Brandeis University (B.A., French Literature), where she studied under philosopher Herbert Marcuse, who became a major intellectual influence.

Studied philosophy at the University of Frankfurt in Germany, engaging with the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

Returned to the U.S. and earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Humboldt University of Berlin (then East Germany) but later completed her doctorate at the University of California, San Diego.

Family Background: Her family lived in a racially mixed neighborhood called “Dynamite Hill” due to frequent Ku Klux Klan bombings targeting Black families. Her mother, Sallye Bell Davis, was a teacher and an active member of the Southern Negro Youth Congress (a communist-affiliated civil rights group), which deeply influenced Davis’s political awakening.

Education:

Attended Brandeis University (B.A., French Literature), where she studied under philosopher Herbert Marcuse, who became a major intellectual influence.

Studied philosophy at the University of Frankfurt in Germany, engaging with the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

Returned to the U.S. and earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Humboldt University of Berlin (then East Germany) but later completed her doctorate at the University of California, San Diego.

2. Political Awakening and Activism

Communist Party USA (CPUSA): Joined in 1968, attracted by its commitment to racial and economic justice. She later ran as the Communist Party’s vice-presidential candidate in 1980 and 1984.

Black Panther Party: Worked closely with the Black Panther Party and was particularly involved with the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-Black communist collective in Los Angeles.

Academic Career: Hired as an assistant professor of philosophy at UCLA in 1969 but was fired by the University of California Board of Regents (led by then-Governor Ronald Reagan) due to her Communist Party membership. This sparked nationwide protests and court battles over academic freedom.

Communist Party USA (CPUSA): Joined in 1968, attracted by its commitment to racial and economic justice. She later ran as the Communist Party’s vice-presidential candidate in 1980 and 1984.

Black Panther Party: Worked closely with the Black Panther Party and was particularly involved with the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-Black communist collective in Los Angeles.

Academic Career: Hired as an assistant professor of philosophy at UCLA in 1969 but was fired by the University of California Board of Regents (led by then-Governor Ronald Reagan) due to her Communist Party membership. This sparked nationwide protests and court battles over academic freedom.

3. The 1970 Arrest, Trial, and International Campaign

Connection to George Jackson: Davis became involved with the Soledad Brothers—three Black inmates accused of killing a prison guard. She developed a close relationship with George Jackson, a radical prison writer and Black Panther.

1970 Marin County Courthouse Incident: Jonathan Jackson (George’s younger brother) staged an armed takeover of a courtroom to demand the release of the Soledad Brothers. Police opened fire, killing four people, including the judge and Jonathan.

Davis as a Fugitive: Firearms used in the incident were registered to Davis, who went into hiding and was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List.

Imprisonment and Trial: She was captured and spent 16 months in prison before her trial. An international “Free Angela Davis” campaign emerged, with protests, letters, and advocacy from figures like John Lennon, Yoko Ono, and the Soviet Union. In 1972, an all-white jury acquitted her of all charges.

Connection to George Jackson: Davis became involved with the Soledad Brothers—three Black inmates accused of killing a prison guard. She developed a close relationship with George Jackson, a radical prison writer and Black Panther.

1970 Marin County Courthouse Incident: Jonathan Jackson (George’s younger brother) staged an armed takeover of a courtroom to demand the release of the Soledad Brothers. Police opened fire, killing four people, including the judge and Jonathan.

Davis as a Fugitive: Firearms used in the incident were registered to Davis, who went into hiding and was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List.

Imprisonment and Trial: She was captured and spent 16 months in prison before her trial. An international “Free Angela Davis” campaign emerged, with protests, letters, and advocacy from figures like John Lennon, Yoko Ono, and the Soviet Union. In 1972, an all-white jury acquitted her of all charges.

4. Intellectual and Activist Contributions

A. Prison Abolition

Davis is a foundational thinker in the prison abolition movement. She argues that prisons are a modern extension of slavery and racial capitalism.

Co-founder of Critical Resistance, an organization dedicated to dismantling the prison-industrial complex.

Key texts: Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003) and Abolition Democracy (2005).

Davis is a foundational thinker in the prison abolition movement. She argues that prisons are a modern extension of slavery and racial capitalism.

Co-founder of Critical Resistance, an organization dedicated to dismantling the prison-industrial complex.

Key texts: Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003) and Abolition Democracy (2005).

B. Black Feminism and Intersectionality

Davis’s work emphasizes intersectionality—how race, class, gender, and sexuality intersect in systems of oppression.

Her book Women, Race & Class (1981) is a landmark study of the often-fraught relationship between the feminist and civil rights movements.

She critiques mainstream feminism for neglecting the struggles of Black, working-class, and incarcerated women.

Davis’s work emphasizes intersectionality—how race, class, gender, and sexuality intersect in systems of oppression.

Her book Women, Race & Class (1981) is a landmark study of the often-fraught relationship between the feminist and civil rights movements.

She critiques mainstream feminism for neglecting the struggles of Black, working-class, and incarcerated women.

C. Anti-Capitalism and Internationalism

Davis frames racism and sexism as integral to global capitalism and imperialism.

She has been a lifelong advocate for Palestinian rights, drawing connections between Black liberation and anti-colonial struggles worldwide.

She actively supports movements like Black Lives Matter, viewing them as heirs to the radical traditions she helped build.

Davis frames racism and sexism as integral to global capitalism and imperialism.

She has been a lifelong advocate for Palestinian rights, drawing connections between Black liberation and anti-colonial struggles worldwide.

She actively supports movements like Black Lives Matter, viewing them as heirs to the radical traditions she helped build.

5. Academic and Public Role

Professor Emerita: Taught at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies departments until her retirement in 2008.

Authorship: Has authored over ten books blending autobiography, theory, and political analysis.

Public Speaking: Remains a sought-after global speaker on justice, abolition, and liberation.

Professor Emerita: Taught at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies departments until her retirement in 2008.

Authorship: Has authored over ten books blending autobiography, theory, and political analysis.

Public Speaking: Remains a sought-after global speaker on justice, abolition, and liberation.

6. Awards and Recognition

International Lenin Peace Prize (1979, from the USSR).

Nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame (2019).

Numerous honorary doctorates worldwide.

Featured in documentaries, songs, and art as an icon of resistance.

International Lenin Peace Prize (1979, from the USSR).

Nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame (2019).

Numerous honorary doctorates worldwide.

Featured in documentaries, songs, and art as an icon of resistance.

7. Personal Life

Identifies as a lesbian and has spoken about the importance of LGBTQ+ solidarity in liberation movements.

A vegetarian and advocate for animal rights, linking it to anti-capitalist and anti-carceral politics.

Identifies as a lesbian and has spoken about the importance of LGBTQ+ solidarity in liberation movements.

A vegetarian and advocate for animal rights, linking it to anti-capitalist and anti-carceral politics.

8. Legacy and Relevance Today

Angela Davis remains a living bridge between the civil rights era and contemporary movements. Her core ideas—especially prison abolition and intersectional feminism—have gained renewed traction in the 21st century. She represents:

Uncompromising radicalism rooted in scholarship and grassroots organizing.

Global solidarity across struggles.

The belief that freedom is a constant struggle, not a destination.

Key Quote

“I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.”

“I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.”

Conclusion

Angami Zapu Phizo

Angami Zapu Phizo (commonly known as A.Z. Phizo or Zapu Phizo; 16 May 1904 – 30 April 1990) was a prominent Naga nationalist leader, freedom fighter, and activist widely regarded as the "Father of the Naga Nation". From the Angami Naga tribe, he spearheaded the Naga independence movement in the mid-20th century, asserting the right of the Naga people to self-determination and sovereignty separate from India. His leadership transformed the Naga struggle from cultural and political assertion into armed resistance, making him a symbol of Naga unity and resistance against integration into the Indian Union.

Early Life & Background

- Born on 16 May 1904 in Khonoma village, Naga Hills District (now Kohima district, Nagaland), British India (then Assam Province).

- From an Angami Naga family with a history of resistance — Khonoma villagers famously fought British forces in 1847 and 1879.

- Educated by Baptist missionaries (under-matriculation level); influenced by Christianity but shaped by Naga traditions.

- Briefly joined the Indian National Army (INA) under Subhas Chandra Bose during World War II, fighting against British rule.

- Early exposure to nationalist ideas through encounters with Mahatma Gandhi and anti-colonial movements.

Political & Activist Career

- In the 1940s, joined the Naga National Council (NNC) — initially formed in 1946 as a political body representing Naga tribes.

- Elected President of the NNC on 28 December 1950 — a position he held until his death.

- Key actions:

- Declared Naga independence on 14 August 1947 (one day before India's independence), claiming Nagas were never part of British India or the Indian Union.

- Organized a plebiscite/referendum in 1951, claiming 99% support for independence (rejected by the Indian government).

- Rejected integration proposals, including the 16-Point Agreement (leading to Nagaland's statehood in 1963).

- In 1954–1956, went underground to lead armed resistance against Indian forces; formed the Naga Federal Government (NFG) and Naga Federal Army (NFA) in 1956.

- Fled to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in December 1956 to seek international support; accused India of genocide and appealed to bodies like the International Commission of Jurists (1962).

- In June 1960, escaped to London via a secret route (using a fake passport), living in exile until his death.

- From exile, continued advocating for Naga sovereignty through writings, interviews, and appeals to the UN, British Parliament, and global forums.

- Opposed the Shillong Accord (1975) signed by some NNC leaders accepting Indian Constitution — viewed it as betrayal.

- His movement used Gandhian non-violence initially (1950s civil disobedience: boycotts, resignations) but shifted to armed struggle after Indian military deployment (1956 onward).

Legacy & Impact

- Revered by many Nagas as the "Father of the Naga Nation" for unifying diverse Naga tribes under a common identity and cause.

- Credited with modeling Nagas as "one people" beyond religious unity (e.g., Christian conversion).

- His uncompromising stance inspired later factions like NSCN (formed 1980), though the movement splintered (e.g., NNC vs. NSCN-IM/K splits).

- Criticized for contributing to prolonged conflict, ethnic divisions, and suffering in Nagaland (armed insurgency, AFSPA imposition).

- Died in exile in Bromley, London on 30 April 1990 (aged 85–86; cause: heart failure or undisclosed).

- Buried at A.Z. Phizo Memorial in Kohima, Nagaland — a site of pilgrimage and remembrance.

- Family legacy: Daughter Adino Phizo became NNC president; his vision influenced ongoing Naga peace talks and sovereignty demands.

Phizo's activism remains polarizing: a heroic patriot to supporters for asserting Naga rights and identity, but a source of division and violence to critics. His life symbolizes the Naga quest for self-determination amid India's post-colonial nation-building.

Arun Krushnaji Kamble (born 14 August 1953-20 December 2009) is a prominent Indian activist, writer, and intellectual from the state of Maharashtra. He is a leading figure in the Dalit-Bahujan movement, particularly known for his work in advocating for the rights of Dalits (Scheduled Castes), Adivasis (Scheduled Tribes), Nomadic Tribes (NT), and Denotified Tribes (DNT) — the most marginalized communities in India.

He is the founder and National President of the Bharatiya Republican Paksha (BRP), a political party rooted in the ideology of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.

Key Areas of Activism and Work

Championing the DNT (Vimukta) Communities:

This is arguably his most significant and lifelong work. The Denotified and Nomadic Tribes (DNTs) were historically labeled as "criminal tribes" by the British colonial government under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. Although "denotified" after independence, they continue to face severe stigma, harassment, and socio-economic deprivation.

Kamble has tirelessly fought for their constitutional recognition, reservation in education and jobs, and an end to police atrocities. He has organized massive rallies and agitations across Maharashtra and at Jantar Mantar in Delhi to highlight their plight.

Academic and Intellectual Contributions:

He is a prolific writer and orator in Marathi. His works critically analyze caste, social justice, and the political economy from an Ambedkarite perspective.

He has authored several books, including:

'Maharashtra: Ek Mahan Dharavi' (Maharashtra: A Great Slum) - A critical analysis of caste and power structures in Maharashtra.

'Dalit Chetna ani Sahitya' (Dalit Consciousness and Literature)

'Bharatiya Republican Ghadari' (The Indian Republican Revolution)

He was a Professor of Marathi and served as the Head of the Department of Marathi at Siddharth College, Mumbai (a college founded by Dr. Ambedkar himself).

Political Activism:

As the head of the Bharatiya Republican Paksha (BRP), he follows the political philosophy of Dr. Ambedkar and the legacy of leaders like Kanshi Ram.

His political activism focuses on consolidating the fragmented Dalit-Bahujan vote into a powerful, independent political force that prioritizes social justice over aligning with mainstream national parties.

He is a sharp critic of both the BJP's Hindutva politics and what he sees as the compromised stance of traditional Dalit parties.

Fight for Housing and Land Rights:

Kamble has been a vocal advocate for the housing rights of the urban and rural poor. He has led agitations demanding the regularization of slums and the provision of affordable housing for marginalized communities in Mumbai and other cities.

Ideological Stance

Arun Kamble is a staunch Ambedkarite. His ideology is centered on:

Annihilation of Caste: Following Ambedkar's core mission.

Social Democracy: Emphasizing constitutional morality, secularism, and equal rights.

Educational and Economic Empowerment: Viewing education as the primary tool for liberation.

Political Assertion: Believing in the need for an independent political voice for the oppressed, free from the influence of both upper-caste dominated parties.

Controversies and Criticism

Direct and Blunt Rhetoric: He is known for his fiery, uncompromising speeches, which often draw criticism from political opponents and those in power.

Political Rivalries: He has been critical of other Dalit leaders and parties, leading to tensions within the broader Dalit movement in Maharashtra.

Arrests and Legal Battles: His activism, particularly in organizing protests, has sometimes led to confrontations with authorities and legal cases.

Legacy and Significance

Voice for the Most Marginalized: Arun Kamble has brought sustained national attention to the issues of Denotified and Nomadic Tribes, a community often overlooked even within broader Dalit discourse.

Bridge Between Academia and Activism: He represents the strong tradition of scholar-activists in the Ambedkarite movement, using his intellectual work to inform and fuel grassroots organizing.

Keeper of the Ambedkarite Flame: In a complex political landscape, he is seen by his supporters as an uncompromising guardian of Ambedkar's radical ideology, constantly pushing for its implementation in its truest form.

Ayyankali

Mahatma Ayyankali (Malayalam: മഹാത്മ അയ്യൻകാളി; 28 August 1863 – 18 June 1941) was a legendary Indian social reformer, Dalit rights activist, revolutionary leader, educator, economist, and lawmaker from the princely state of Travancore (now part of Kerala). Born into the Pulaya community (a Dalit caste historically subjected to extreme untouchability, slavery-like conditions, and exclusion as "unseeables" and "unapproachables"), he emerged as one of the most fearless and innovative fighters against caste oppression in Kerala. Often called the "King of Pulaya" or "Mahatma of the Oppressed", his non-violent yet resolute struggles for dignity, education, public access, and labour rights transformed the socio-political landscape of Kerala and paved the way for Dalit emancipation.

Early Life & Background

- Born on 28 August 1863 in Venganoor village, Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum) district, Travancore, to parents Ayyan and Mala in a poor Pulaya family of agricultural labourers.

- Faced severe caste discrimination: Pulayas were barred from public roads, schools, temples, covering upper bodies (for women), and basic human interactions; upper castes considered even their shadows polluting.

- Illiterate himself (no formal education due to caste barriers), but self-taught and exceptionally perceptive; worked as a farm labourer and later cleared jungles for a landlord, earning a small plot of land (rare for Dalits then).

- Tall and strong (reportedly 6 ft 6 inches), he was warned not to play with upper-caste boys or assert equality.

- Married Chellamma in 1888; had seven children.

Activism & Major Struggles

Ayyankali's activism began in the 1890s–1900s, using innovative, direct-action tactics (strikes, boycotts, cultural resistance) rather than petitions alone.

- Villuvandi Samaram (Bullock Cart Rebellion, 1893): Defied the ban on Dalits using public roads by riding an ox-cart from Venganoor to Neyyattinkara. When attacked by upper-caste gangs, it escalated into the first armed Dalit resistance in modern Indian history; he fought back with supporters, leading to clashes but forcing concessions.

- Right to Education & School Strikes: Organized agricultural labourers' strikes (first successful in Kerala) against upper-caste landlords to demand Dalit children's admission to government schools. In 1907–1910, Pulaya children were admitted after prolonged agitation.

- Dress Code & Dignity Struggles: Fought against the "breast tax" or restrictions on Pulaya women's upper-body covering; advocated for equal dignity.

- Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham (SJPS, 1907): Founded the Association for the Protection of the Poor (later Pulaya Mahasabha), uniting oppressed castes (Pulaya and others) for education, land rights, labour rights, legal aid, and self-respect. Raised funds for Pulaya-run schools and published journals.

- Political Representation: Nominated in 1910 as the first Dalit member of the Sree Moolam Popular Assembly (Travancore's legislative council). Demanded and secured concessions like education access, land reforms, and social support for downtrodden groups.