From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

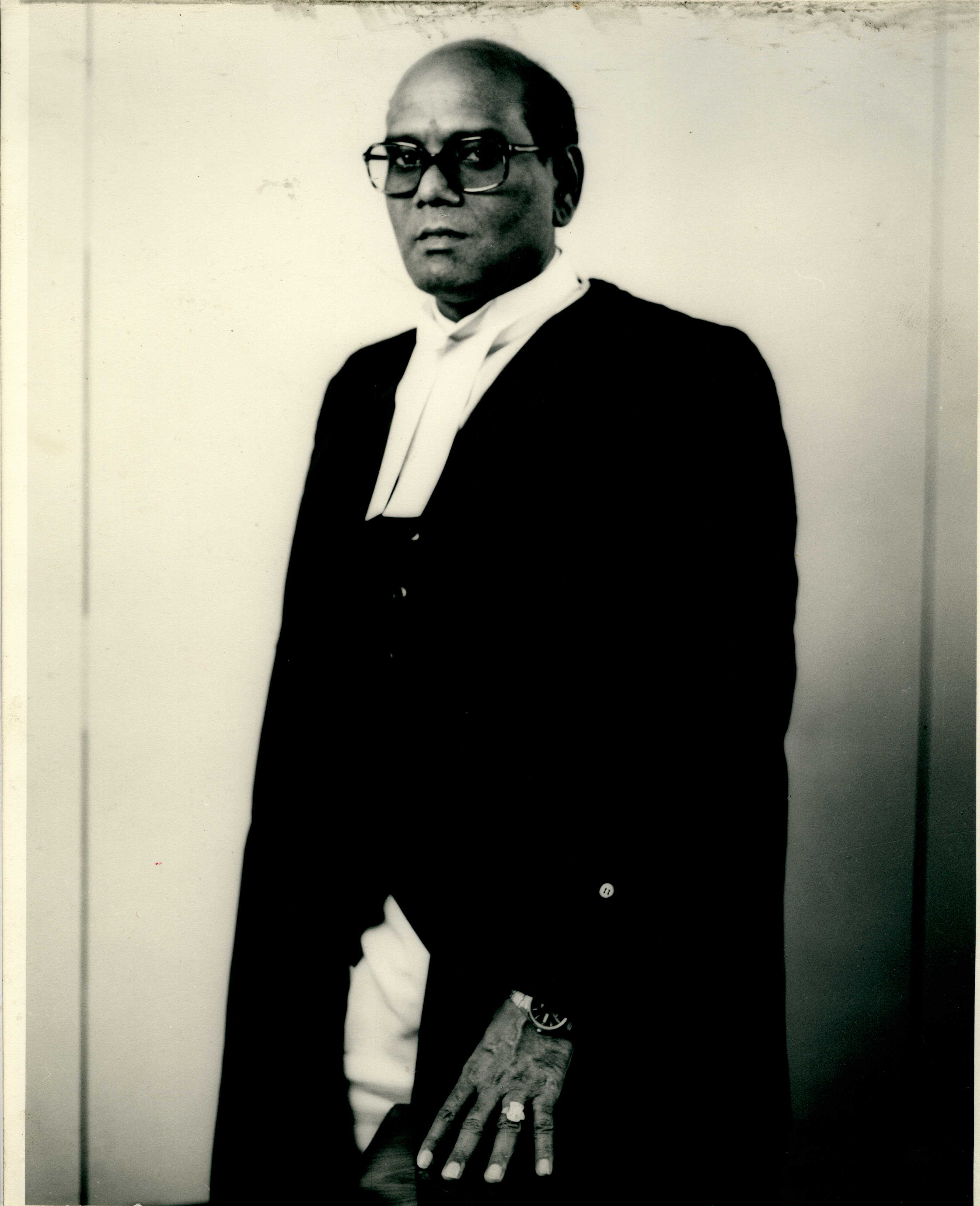

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJustice Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai

Justice Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai was born on 24 November 1960 in Amravati, Maharashtra, into a family deeply rooted in social activism and the Ambedkarite movement. He spent much of his childhood in a modest slum locality in Amravati's Frezarpura area, reflecting humble beginnings that shaped his commitment to social justice. His early schooling took place at a local municipal primary school in Amravati, followed by Chikitsak Samuha Shirolkar Madhyamik Shala and Holy Name High School in Mumbai. He pursued higher education at Amravati University, earning degrees in commerce and law (B.Com and LL.B.), before obtaining a B.A. LL.B. from Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar College of Law, Nagpur University.

Family Background

Gavai hails from a prominent Scheduled Caste (SC) family following Buddhism, influenced by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's 1956 mass conversion movement. His father, Ramkrishna Suryabhan (R.S.) Gavai (1929–2015), was a veteran Ambedkarite leader, founder of the Republican Party of India (Gavai faction), Member of Parliament, and Governor of Bihar, Sikkim, and Kerala. R.S. Gavai was a close associate of Ambedkar and played a key role in Dalit politics. His mother, Kamaltai Gavai, was a former school teacher. Gavai's brother, Rajendra Gavai, is a politician, and his daughter, Karishma Gavai, serves as an assistant professor at National Law University, Nagpur. The family remains inspired by Ambedkar's ideals of equality and constitutionalism.

Legal Career

Gavai enrolled as an advocate on 16 March 1985 and began his practice under the mentorship of Bar. Raja S. Bhonsale, a former Advocate General and Bombay High Court judge, until 1987. He then practiced independently at the Bombay High Court from 1987 to 1990, shifting focus to the Nagpur Bench thereafter. Specializing in constitutional, civil, criminal, and administrative law, he represented clients including the Nagpur Municipal Corporation, Amravati Municipal Corporation, Amravati University, and various corporations like SICOM and DCVL.

Key roles included:

- Assistant Government Pleader and Additional Public Prosecutor at the Bombay High Court, Nagpur Bench (August 1992–July 1993).

- Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor for the Nagpur Bench (from 17 January 2000).

Known for his merit-based approach, two of his juniors later became High Court judges. Initially inclined toward politics like his father, Gavai chose law to advocate for marginalized communities.

Judicial Career

Bombay High Court (2003–2019)

- Appointed Additional Judge on 14 November 2003 (nominated by then-CJI V.N. Khare; appointed by President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam).

- Became Permanent Judge on 12 November 2005.

- Served for 16 years, presiding over benches at Mumbai (principal seat), Nagpur, Aurangabad, and Panaji. Handled diverse cases, emphasizing procedural fairness and rights of the underprivileged.

Supreme Court of India (2019–2025)

- Elevated as a Supreme Court Judge on 24 May 2019 (nominated by then-CJI Ranjan Gogoi; appointed by President Ram Nath Kovind). The Collegium highlighted his seniority, integrity, merit, and need for SC representation (he was the first SC judge appointed to the Supreme Court in nine years).

- Served until 13 May 2025, authoring over 464 judgments across 772 benches—an average of more than 70 per year. His work spanned constitutional law (highest share), criminal law (154 judgments), service law (53), civil matters (44), taxation (34), and property issues (26). Peak authorship: 98 judgments in 2022 (71% rate).

Chief Justice of India (2025)

- Sworn in as the 52nd CJI on 14 May 2025 by President Droupadi Murmu, succeeding CJI Sanjiv Khanna. His six-month tenure (until 23 November 2025) made him the second Dalit CJI (after K.G. Balakrishnan) and the first Buddhist CJI, marking a historic milestone for diversity. He succeeded by Justice Surya Kant on 24 November 2025.

- As CJI, he chaired the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) as executive chairman (from 13 November 2024) and served as ex-officio patron-in-chief. He prioritized case pendency (over 81,000 Supreme Court cases), judicial vacancies, and diversity in appointments.

He also held academic roles as Chancellor of Maharashtra National Law University, Nagpur, and other NLUs.

Notable Judgments and Contributions

Justice Gavai's jurisprudence emphasized constitutional equity, due process, and protection of marginalized rights, often drawing from his personal experiences. He authored or co-authored around 300 landmark decisions. Key ones include:

| Case/Year | Bench Role | Key Ruling/Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Article 370 Abrogation (2023) | Member, 5-judge Constitution Bench | Unanimously upheld the abrogation as constitutionally valid; directed Jammu & Kashmir statehood restoration and elections by September 2024. |

| Electoral Bonds Scheme (2024) | Member, Constitution Bench (Association for Democratic Reforms v. Union of India) | Struck down the scheme as violative of Article 19(1)(a) (right to information), enhancing electoral transparency. |

| Demonetisation (2023) (Vivek Narayan Sharma v. Union of India) | Authored majority opinion | Upheld the 2016 scheme, affirming Union's power to invalidate currency and RBI consultation. |

| Sub-Classification in SC/ST Quotas (2024) (State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh) | Concurring opinion, 7-judge Bench (6:1) | Allowed sub-classification within SC/ST for equitable affirmative action; stressed excluding "creamy layer" to prevent "double injury" to the most backward, quoting Justice Krishna Iyer. Noted SCs as "heterogeneous" groups. |

| Bulldozer Demolitions (2024) (In Re: Directions in Demolition of Structures) | Co-authored with KV Viswanathan | Declared punitive demolitions without due process unconstitutional; violated rule of law and separation of powers. Called it "immense satisfaction" for protecting shelter rights. |

| Rahul Gandhi Defamation Conviction Stay (2023) | Member Bench | Stayed conviction, highlighting far-reaching impacts like parliamentary disqualification. |

| Prashant Bhushan Contempt (2020) | Member Bench (In Re: Prashant Bhushan) | Held advocate guilty for tweets criticizing the Supreme Court; imposed symbolic Re. 1 fine (or 3 months' imprisonment if unpaid). |

| SC/ST Act Safeguards Review (2019) (Union of India v. State of Maharashtra) | Member Bench | Restored stringent arrest provisions, rejecting preliminary inquiries or approvals to prevent misuse dilution. |

| Presidential Reference No. 1 of 2025 (2025) | Contributed to advisory opinion | Ruled courts cannot impose timelines on President/Governors for bills; rejected "deemed assent" except for prolonged inaction; actions under Articles 200/201 largely non-justiciable. |

| ED Chief Extension (2025) | Headed Bench | Declared extension to SK Mishra illegal, violating 2021 Common Cause judgment limits. |

| Post-Facto Environmental Clearances (2025) (Confederation of Real Estate Developers v. Vanashakti) | Majority (2:1) in review | Allowed exceptional post-facto clearances, recalling a stricter prior ruling; described environmental law as a "living framework." |

| Manish Sisodia Bail (2024) | Member Division Bench | Granted bail after 17 months, emphasizing right to speedy trial. |

| Dying Declarations (2023) (Irfan v. State of U.P.) | Co-authored | Cannot be sole conviction basis; listed 11 factors for reliability in death penalty cases. |

| Arbitration Agreements & Stamp Duty (Recent) | Addressed enforceability | Non-payment of stamp duty does not invalidate agreements, easing arbitration.

|

His judgments often critiqued arbitrary executive actions and reinforced procedural safeguards, like in arrest guidelines and against "bulldozer justice."

Personal Life and Legacy

A devout Buddhist, Gavai's life embodies Ambedkar's vision of education, agitation, and organization for Dalit upliftment. Upon becoming CJI, he paid tribute to Ambedkar and touched his mother's feet, symbolizing respect for roots. He is married (details private) and maintains a low-profile personal life focused on family and social causes.

Gavai's elevation symbolized breaking judicial elitism, with the Supreme Court achieving historic SC representation (three judges in January 2025, including him and Justice Prasanna B. Varale—the first two Buddhists simultaneously). His tenure advanced diversity in appointments but faced criticism for perceived inconsistencies, such as elevating Justice Vipul Pancholi amid controversy, diluting gubernatorial checks, and situational approaches to bail in political cases. Recent X discussions highlight his retirement as a "disappointing" streak for CJIs, citing lapses in enforcing court orders and resisting executive influence, though praising his equity-focused rhetoric. No major awards are noted, but his legacy endures in over 95 years of judicial service, inspiring marginalized communities.

Post-retirement, Gavai plans to advocate for judicial reforms and Ambedkarite causes, leaving an indelible mark as a bridge between constitutional ideals and lived realities.

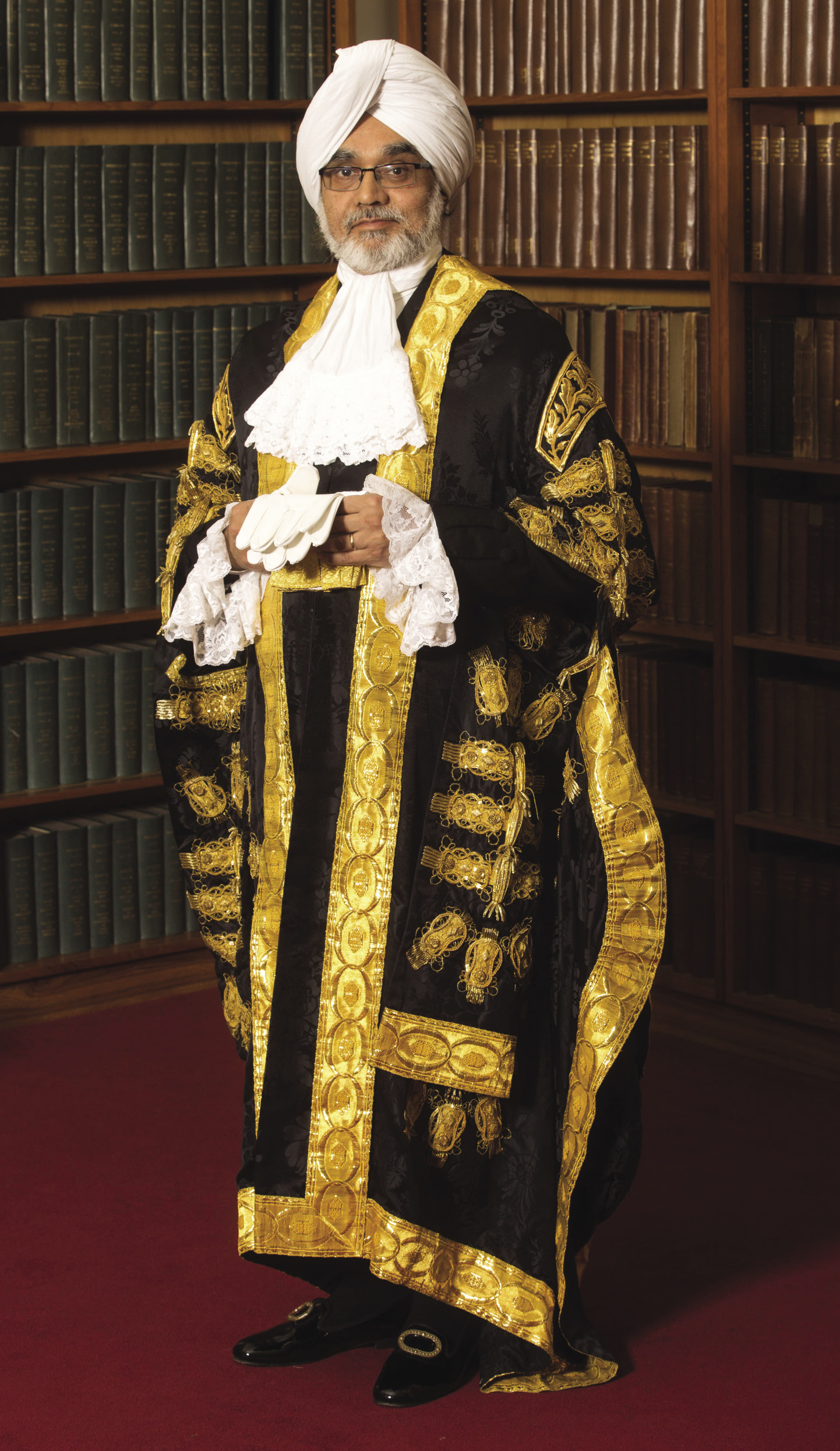

Prof B.C. Nirmal

Professor B.C. Nirmal (full name Bagish Chandra Nirmal or Brijesh Chandra Nirmal; born February 19, 1952) is a distinguished Indian legal scholar, academic, and former university administrator specializing in International Law and Human Rights Law. He is widely regarded as one of India's leading experts in these fields, with over 40+ years of teaching, research, and administrative experience. He is not the former Chairperson of the National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) — that role has been held by figures like P.L. Punia, Vijay Sampla, Kishor Makwana, and others in recent years, with no records linking Prof. Nirmal to the NCSC chairmanship or membership.

(Note: There may be some confusion with other individuals or commissions, but based on verified sources, Prof. B.C. Nirmal has no association with the NCSC chairmanship.)

Early Life and Education

- Born on February 19, 1952.

- He holds a B.Sc. degree, followed by LL.M. and Ph.D. in Law.

- His academic journey focused on advanced studies in international law, human rights, and related constitutional aspects.

Academic and Professional Career

- Long association with Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Varanasi:

- Served as Professor of Law at the Faculty of Law.

- Former Head and Dean of the Faculty of Law, BHU.

- Recognized as one of the top professors at BHU in legal education.

- Vice Chancellor of the National University of Study and Research in Law (NUSRL), Ranchi, Jharkhand (a prominent National Law University).

- He has been actively involved in legal education reforms, clinical legal education, and challenges in teaching law in India.

- Positions and affiliations:

- Executive Council Member of the Indian Society of International Law.

- Vice President, All India Law Teachers Association (or similar bodies).

- Participated in international forums, such as the Xiamen Academy of International Law (China), where he has been featured as a professor from BHU.

- He has delivered lectures, keynote addresses, and contributed to judicial education, human rights discourse, and international law conferences.

Research and Publications

- Google Scholar citations: Over 140 (as per profiles).

- Key areas: International Law, Human Rights Law, Constitutional Law implications for marginalized groups, legal education.

- Notable contributions include writings on human rights mechanisms, international humanitarian law, and the role of law in social justice.

- He has supervised numerous Ph.D. scholars and been involved in peer-reviewed journals and books on these topics.

- Videos and talks (e.g., on YouTube) feature him discussing Human Rights Law in depth.

Legacy and Recognition

- Widely acclaimed as a mentor to generations of law students and scholars in India.

- His work emphasizes the intersection of law with social justice, human rights protection, and global legal standards.

- He continues to be referenced in academic circles, with tributes (e.g., messages and reels) highlighting his contributions to legal academia.

- No specific information indicates he belongs to SC/ST or a disadvantaged community in public records — his profile aligns with that of a highly accomplished academic from a scholarly background, focused on merit-based achievements in law.

Charu Chandra Biswas (CIE) was a prominent Indian jurist and politician known for his roles in the judiciary and the Union Cabinet of India.

🏛️ Key Biographical Details

Born: 21 April 1888, Calcutta, British India.

Died: 12 December 1960 (aged 72).

Political Party: Indian National Congress.

Spouse: Suhasini Biswas.

Children: 6 daughters.

Father: Ashutosh Biswas.

⚖️ Legal and Judicial Career

Lawyer: He began his career as a lawyer in the Calcutta High Court.

Judge: He was appointed a Judge of the Calcutta High Court in February 1940.

Vice Chancellor: He served as the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta from 1949–1950.

Honour: The imperial British government appointed him a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) in the 1931 Birthday Honours list.

Political Career

Member of Parliament (MP): He was elected to the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of the Indian Parliament) representing West Bengal from 1952 to 1960.

- Cabinet Minister: He served as the Union Minister of Law and Minority Affairs in Jawaharlal Nehru's cabinet from 1952 to 1957, succeeding B. R.

Ambedkar. - Leader of the House: He was the Leader of the House in the Rajya Sabha from February 1953 to November 1954.

India

India

Indian

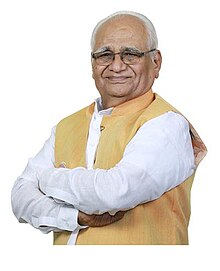

IndianJustice Pritinker Diwaker

Justice Pritinker Diwaker (born November 22, 1961) is a retired Indian jurist who served as the 50th Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court, one of India's oldest and busiest high courts. His judicial career, spanning over three decades, is marked by a transition from advocacy in central India to high-level judicial administration in Uttar Pradesh. Known for his commitment to judicial accessibility, case management reforms, and humane interpretations of the law, Diwaker retired on November 21, 2023, upon reaching the age of superannuation (62 years for high court judges). As a first-generation lawyer in his family, his journey exemplifies dedication and resilience in the legal profession.

Early Life and Education

Born in 1961, Justice Diwaker hails from a background in central India, specifically associated with Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh (now part of the unified Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh judicial ecosystem). Details about his family remain largely private, with public records emphasizing his role as a pioneering lawyer from a non-legal family lineage. He pursued his legal education at Rani Durgawati Vishwavidyalaya (also known as Durgawati University) in Jabalpur, graduating with an LL.B. degree in 1984. This institution, known for its rigorous legal training, laid the foundation for his career in constitutional, civil, and criminal law.

Legal Practice and Advocacy

Upon enrollment as an advocate with the Bar Council of Madhya Pradesh in 1984, Diwaker began practicing at the principal bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court in Jabalpur. His practice focused on a broad spectrum of cases, including constitutional matters, civil disputes, and criminal trials. He served as standing counsel for major public sector entities such as Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL), State Bank of India (SBI), Chhattisgarh Gramin Bank, Bank of Baroda, and IDBI Bank, showcasing his expertise in corporate and public interest litigation.

Diwaker's advocacy career gained momentum after the bifurcation of Madhya Pradesh and the establishment of the Chhattisgarh High Court on November 1, 2000. He shifted his practice to Bilaspur, the new high court's seat, where he was designated a Senior Advocate by the Chhattisgarh High Court in January 2005—a rare honor reflecting his standing in the bar. He also contributed to legal governance as a member of the Madhya Pradesh State Bar Council for seven years and the Chhattisgarh State Bar Council for five years, advocating for professional standards and bar reforms.

Judicial Career

Diwaker's elevation to the bench was a pivotal moment, though he initially hesitated to accept the offer from the collegium in 2009, citing his deep attachment to advocacy. He was appointed as a Judge of the Chhattisgarh High Court on March 31, 2009, where he served for nearly a decade, handling diverse cases and earning praise for his satisfaction in judicial duties.

Transfer to Allahabad High Court

On October 3, 2018, Diwaker was transferred to the Allahabad High Court under Article 222 of the Constitution, as recommended by the Supreme Court Collegium headed by then-Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra. This inter-high court transfer, aimed at addressing judicial administrative needs, was controversial for Diwaker. In his retirement speech on November 21, 2023, he candidly alleged that the order "seemed to have been issued with an ill intention to harass me," describing it as a "sudden turn of events" and an undeserved "shower of extra affection" from CJI Misra for unknown reasons. Despite initial reluctance and a representation against it (which the collegium rejected in September 2018), he assumed office and adapted effectively.

At Allahabad, Diwaker quickly rose through seniority. Following the elevation of Chief Justice Rajesh Bindal to the Supreme Court on February 9, 2023, he was appointed Acting Chief Justice on February 13, 2023, as the senior-most puisne judge—a convention under judicial norms.

Tenure as Chief Justice

On March 26, 2023, President Droupadi Murmu appointed Diwaker as the 50th Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court, with Uttar Pradesh Governor Anandiben Patel administering the oath in a ceremonial event attended by judges, lawyers, and dignitaries. His eight-month tenure (until November 21, 2023) focused on modernizing court operations amid a heavy caseload—Allahabad High Court handles over 1 million pending cases annually.

Key administrative initiatives included:

- Enhancing judicial accessibility through digital tools and streamlined case management.

- Reforms in prison systems and societal upliftment, praised for reshaping institutional fabrics.

- Addressing lawyer grievances, such as referring a Bar Council of Uttar Pradesh complaint on police lathi charges in Hapur to a special committee chaired by Justice Manoj Kumar Gupta.

- Suo motu cognizance of deficiencies in child care institutions, issuing directions for urgent reforms.

- Directing state support for victims of animal attacks, extending victim compensation schemes akin to those under the CrPC.

Diwaker emphasized work-life balance for judges and praised the bar-bench fraternity, noting the "perfect balance" his family maintained between professional demands and personal life. He credited CJI D.Y. Chandrachud's collegium for "rectifying the injustice" of his 2018 transfer by recommending his elevation to Chief Justice.

Notable Judgments

Throughout his career, Diwaker authored or co-authored several landmark decisions emphasizing constitutional fidelity, litigant rights, and procedural fairness. Below is a table summarizing key judgments:

| Case Name | Year | Key Holding | Bench |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shashank Singh v. Hon'ble High Court of Judicature at Allahabad | 2021 | Under Article 233, judicial officers cannot compete for District Judge posts via the advocate quota, regardless of prior bar experience; direct recruitment rules are sacrosanct. | Single Bench (Diwaker, J.) |

| Vimal Kumar Maurya v. State of U.P. | 2023 | Acquitted appellant of life sentence under IPC Section 326-A (acid attack); evidence insufficient for conviction without corroboration. | Division Bench (Diwaker, J. & Srivastava, J.) |

| Munni Devi v. State of UP | 2020 | Authentic dying declarations can form the sole basis for conviction if voluntary and credible; no mandatory corroboration needed. | Division Bench (Diwaker, J.) |

| Unnamed Blacklisting Case (Agra Development Authority) | ~2020 | Blacklisting notices must specify consequences and grounds; procedural fairness essential to prevent arbitrary state action. | Single Bench (Diwaker, J.) |

| Unnamed Liquor Policy PIL | ~2021 | State liquor business notifications are policy matters; courts cannot mandate specific framing unless unconstitutional. | Division Bench (Diwaker, J.) |

| Amity University Attendance PIL | 2023 | Allowed MBA student to appear for exams despite portal glitch showing low attendance; directed technical fixes for equity. | Single Bench (Diwaker, CJ) |

Legacy and Retirement

Diwaker's farewell on November 21, 2023, was a full court reference attended by judges like Justices Manoj Kumar Gupta and Attau Rahman Masoodi, who lauded his "lasting impact" through judgments and reforms. Lawyers from districts like Meerut hoped his legacy would inspire accessible justice. Post-retirement, he has maintained a low profile, with no public engagements reported as of November 2025.

His candid retirement remarks on the 2018 transfer sparked discussions on collegium transparency, underscoring the human element in judicial appointments. Diwaker's career, from a reticent advocate to a reform-oriented Chief Justice, remains a testament to judicial integrity amid systemic challenges.

Justice P.B. Sawant

Justice P.B. Sawant (full name Prakash Balkrishna Sawant or simply P.B. Sawant; 30 June 1930 – 15 February 2021) was a distinguished Indian jurist, former Judge of the Supreme Court of India, and a prominent post-retirement public figure known for his staunch defense of civil liberties, human rights, secularism, anti-communalism, anti-caste principles, and the rights of the poor and oppressed. Often described as one of the "last creative judges" with strong progressive convictions (comparable to Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer), he combined judicial impartiality with deep social commitment, remaining active in public life for over 25 years after retirement.

Early Life and Education

Born on 30 June 1930 (exact place not widely detailed, but associated with Maharashtra/Bombay region).

- Earned a B.A. (Special) Honours in Economics and LL.B. from Bombay University (now University of Mumbai).

- Began his career as a lecturer at New Law College, Bombay (around 1965), teaching subjects like Private International Law and Constitutional Law.

- Enrolled as an advocate in 1957; practiced at the Bombay High Court (practicing all branches of law, often representing laborers, farmers, and marginalized groups) and later at the Supreme Court of India.

Judicial Career

- 1973: Appointed as a Judge (Additional, later permanent) of the Bombay High Court, serving for over 16 years.

- Notable: Conducted an official inquiry into the Air-India aircraft crash in June 1982 (a significant aviation disaster probe).

- 6 October 1989: Elevated to Judge of the Supreme Court of India.

- Served until retirement on 29 June 1995 (reached superannuation age).

- Key contributions on the bench:

- Part of constitution benches in landmark cases like the Mandal Commission (reservation for OBCs) and S.R. Bommai (1994 – federalism and misuse of Article 356).

- Authored/co-authored judgments upholding media freedom (e.g., 1995 ruling that airwaves are public property, rejecting state monopoly).

- Known for impartiality despite perceived leftist leanings from pre-judicial activism; emphasized civil liberties, human rights, and constitutional values.

Post-Retirement Activism and Public Roles (1995–2021)

After retirement, Justice Sawant became a vocal public intellectual and activist, often chairing inquiries and tribunals on social justice issues:

- Chairman, Press Council of India (PCI): Revitalized the body during his tenure; introduced guidelines (e.g., no publication of exit polls until all voting ends); defended media rights and fought attempts to weaken the council. Also served as Chairman of the World Association of Press Councils.

- 2002: Served on the Indian People's Tribunal (with Justice Hosbet Suresh and others) probing communal violence and related issues.

- 2002 Gujarat Riots Probe: Part of an independent panel investigating the 2002 Gujarat violence.

- 2003: Chaired the P.B. Sawant Commission (appointed by Maharashtra government) to investigate corruption allegations against four state ministers (Nawab Malik, Padmasinh Patil, Suresh Jain, Vijaykumar Gavit).

- 2017: Co-convener of the Elgar Parishad conclave in Pune (December 31, 2017), which addressed Dalit rights and was controversially linked to later Bhima Koregaon events.

- Other involvements: President of Mahatma Phule Samta Pratishthan; active in anti-communal, anti-caste campaigns; supported rights of the poor, farmers, laborers, and oppressed sections.

- Famous incident: Filed a ₹100 crore defamation suit against Times Now (2008) after the channel mistakenly used his photo (instead of another judge) while reporting a provident fund scam—highlighting his stand against media irresponsibility.

Personal Life and Legacy

- Survived by his wife, two daughters, and a son.

- Died on 15 February 2021 at his home in Pune due to cardiac arrest, aged 90 (or 91 in some reports).

- Tributes described him as a "champion of civil liberties," a defender of democracy, secularism, and the marginalized; his political experience (pre-judiciary leftist leanings) enhanced rather than compromised his judicial integrity.

- Remembered in outlets like Frontline, The Wire, SCC Online, SabrangIndia, and others for upholding constitutional morality, media ethics, and social justice even after retirement.

Justice P.B. Sawant exemplified a judge who transcended the bench to engage actively with society's pressing issues, leaving a legacy as a principled, progressive voice in Indian jurisprudence and public life.

Justice S. Ashok Kumar

Justice S. Ashok Kumar was a notable Indian judge who served in the Madras High Court and the Andhra Pradesh High Court. His life and career were marked by significant judicial contributions but also by controversy surrounding his caste status and religious identity. Below is a comprehensive account of his background, career, and the controversies associated with him, based on available information.

Early Life and Background

- Birth and Family: S. Ashok Kumar was born on July 5, 1947, in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, to parents who were Christian Dalits. His original name was S. Antony Samy.

- Religious Conversion: He claimed to have converted to Hinduism in 1971, changing his name to S. Ashok Kumar in 1974. This conversion was significant because it allowed him to claim Scheduled Caste (SC) status under the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, which restricts SC benefits to Hindus, Sikhs, or Buddhists.

- Education: While specific details about his educational qualifications are not widely documented, he pursued a legal career, which suggests he completed a law degree and other necessary qualifications for judicial service.

Judicial Career

- Initial Appointment: In 1987, S. Ashok Kumar was directly recruited as a District Judge in Tamil Nadu under a post reserved for Hindu Scheduled Caste candidates. This appointment was facilitated by his claimed conversion to Hinduism and his SC status.

- Judicial Roles:

- He served as a District Judge in various courts in Tamil Nadu.

- He was later elevated to the Madras High Court as a judge.

- He also served as a judge in the Andhra Pradesh High Court.

- Tenure and Contributions: Justice Kumar served as a judge until his death in 2009. During his tenure, he handled a range of cases typical of High Court judges, though specific landmark judgments attributed to him are not widely detailed in available records. His career was notable for his rise from a reserved category background to a prominent judicial position.

Controversy Over Caste and Religious Identity

Justice S. Ashok Kumar’s career was overshadowed by a significant controversy regarding his caste status and religious identity, which came to light after his death in a 2022 Madras High Court case (W.P.No.33764 of 2019).

- Allegations of Misrepresentation:

- Kumar claimed Hindu SC status to secure his judicial appointment in 1987 and even contested a reserved SC assembly seat in 1987. However, it was alleged that he remained a practicing Christian, which would disqualify him from SC benefits under the 1950 Order.

- Evidence cited in the 2022 judgment included:

- His marriage to a Christian woman in a Christian ceremony.

- His children being raised as Christians and married in Christian ceremonies.

- His burial in a Christian cemetery in Tirunelveli in 2009, with a Christian epitaph on his tombstone.

- His family’s continued practice of Christianity, including his wife’s burial in a Christian cemetery.

- These factors led to accusations that Kumar misrepresented his religious identity to avail reservation benefits meant for Hindu SC candidates.

- Legal Scrutiny:

- The controversy arose in a case involving a petitioner challenging the validity of Kumar’s SC status, arguing that he had obtained his judicial post under false pretenses.

- The Madras High Court’s 2022 judgment noted that Kumar’s claim of conversion to Hinduism was questionable, as his lifestyle and family practices suggested he remained a Christian. The court emphasized that SC status is tied to both caste and religion under the 1950 Order, and Kumar’s actions appeared inconsistent with his claimed Hindu identity.

- However, since Kumar had passed away in 2009, no direct legal action could be taken against him, but the case highlighted issues of reservation misuse and the need for verification of caste and religious claims.

Personal Life

- Family: Kumar was married, and his wife was a Christian. He had children who were raised as Christians and married in Christian ceremonies, as noted in court records.

- Death: He passed away on October 29, 2009, and was buried in a Christian cemetery in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu. His burial, with a Christian epitaph, became a key point in the controversy over his religious identity.

Legacy and Impact

- Judicial Legacy: Justice S. Ashok Kumar’s contributions to the judiciary, particularly in the Madras and Andhra Pradesh High Courts, are part of his professional record. However, specific details of his judgments or legal philosophy are not widely documented in public sources.

- Controversy’s Broader Implications: The controversy surrounding his caste and religious identity sparked discussions on the integrity of reservation policies in India. It raised questions about the mechanisms for verifying caste and religious claims, especially for high-stakes positions like judicial appointments. The 2022 Madras High Court ruling underscored the importance of ensuring that reservation benefits are availed by eligible candidates.

Additional Context

- Caste and Reservation in India: The Scheduled Caste reservation system is designed to uplift historically disadvantaged communities. The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, explicitly limits SC status to Hindus, Sikhs, and Buddhists (with some amendments over time). This makes religious identity a critical factor in determining eligibility, which was central to Kumar’s case.

- Lack of Public Records: Beyond the 2022 court case and some judicial records, detailed biographical information about Justice Kumar’s life, such as his education, specific judicial contributions, or personal writings, is sparse in publicly available sources. This limits the depth of insight into his career beyond the controversy.

Y. S. Tambe

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for feedback