List of Caste or Dalit Movement in India before independence

The term Dalit was firstly used by Jyotirao Phule for the oppressed classes or untouchable castes of the Hindu. Mahatma Gandhi used Harijan for the oppressed or depressed or Dalit classes which means 'Children of God'. Here, we are giving the list of Caste or Dalit Movement in India before independence, which is very useful for the competitive examinations like UPSC-prelims, SSC, State Services, NDA, CDS, and Railways etc

Compiled by DC Gahmari

List of Caste or Dalit Movement in India before independence

The term Dalit was firstly used by Jyotirao Phule for the oppressed classes or untouchable castes of the Hindu. Mahatma Gandhi used Harijan for the oppressed or depressed or Dalit classes which means 'Children of God'.

List of Caste Movement in India before independence

Movement

Founders

Causes and Consequences

Nair Movement

Started under the leadership of CV Raman Pillai, K Rama Krishna Pillai and M. Padmanabha Pillai in 1861.

1. Against Brahminic dominion

2. The Malayali Memorial was formed by Raman Pillai in 1891 and Nair Service Society was set up by Padmanabha Pillai in 1914.

Satyashodhak Movement

Jyotirao Phule founded in 1873 (Maharashtra).

1. For emancipation of low castes, untouchables and widows.

2. Against Brahminic dominion

Justice Party Movement

Started under the leadership of Dr. T.M Nair, P. Tyagaraja Chetti and C.N Mudalair in 1916.

1. Against Brahminic dominion in government services, education and politics.

2. The South Indian Liberation Federation (SILF) was formed in 1916.

3. The efforts yielded in the passing of 1930 Government Order providing reservations to groups.

Self-Respect Movement

Started under the leadership of EV Ramaswami Naicker or Periyar in 1925.

1. Against caste system and biased approach of Brahmins.

2. Kudi Arasu journal was started by Periyar in 1910.

Depressed Classes Movement (Mahar Movement)

Started under the leadership of BR Ambedkar in 1924.

1. For the upliftment of depressed classes.

2. Against untouchability

3. Depressed Classes Institution was founded in 1924.

4. Marathi fortnightly Bahiskrit Bharat was started in 1927.

5. Establishment of Samaj Samta Sangh in 1927.

6. Establishment of Scheduled Caste Federation in 1942 that propagated their views on depressed classes.

Congress Harijan Movement

1. For elevating the social status of the lower and backward classes.

2. Establishment of All-India Anti-Untouchability League in 1932.

3. Weekly Harijan wa founded by Gandhi in 1933.

Kaivartas Movement

Started by Kaivartas

1. Laid the foundation of the Jati Nirdharani Sabha in 1897.

2. Laid the foundation of Mahishya Samiti in 1901.

Nadar Movement by 1910, Tamilnadu

Ezhava Movement by Narayan Guru

1928, Kerala

Mahar Movement by BR Ambedkar

1920, Maharastra

Namshudra Movement by Narayan Guru

191901, Faridpur , Bengal

Hence, we can say, the Caste or Dalit Movement in India before independence was the resultant of hatred being generated by the Brahmanism. According to Brahmanism, Dalit or lower caste is assigned to serve the three varna which means Brahmin, Kshatriye and Vaishyas. They don't have right to take higher education and were denied social-economic and political status.

Nadar Movement by 1910, Tamilnadu

Ezhava Movement by Narayan Guru

1928, Kerala

Mahar Movement by BR Ambedkar

1920, Maharastra

Namshudra Movement by Narayan Guru

191901, Faridpur , Bengal

Dalit Movements in India After 1947

https://www.worldwidejournals.com/paripex/recent_issues_pdf/2016/August/dalit-movements-in-india-after-1947_August_2016_2190069145_3805365.pdf

Dr.K.Sravana Kumar

M.A.Ph.D. Lecturer in History, N.B.K.R. Science and Arts College,

Vidya Nagar, Kota Mandal, Nellore District. Andhra Pradesh,

India-524 413.

ABSTRACT

The word “Dalit” may be derived from Sanskrit, and means “crushed”, or “broken to pieces”. It was perhaps first used by Jyotirao Phule in the nineteenth century, in the context of the oppression faced by the erstwhile “untouchable” castes of the Hindus. Moahatma Gandhi adopted the word “Harijan,” translated roughly as “Children of God”, to identify the former Untouchables. According to the Indian Constitution the Dalits are the people coming under the category Scheduled castes‘.Currently, many Dalits use the term to move away from the more derogatory terms of their caste names, or even the term “Untouchable.” The contemporary use of “Dalit” is centered on the idea that as a people, the group may have been broken by oppression, but they survive and even thrive by finding meaning in the struggle of their existence. Dalit is now a political identity

Original Research Paper History

Major Causes of the Dalit Movement

The Dalit Movement is the result of the constant hatred being generated from centuries from the barbaric activities of the upper castes of India. Since Dalits were assigned the duties of serving the other three Varnas, that is all the non– Dalit, they were deprived of higher training of mind and were denied social-economic and political status.The division of labour led to the division of the labourers, based on inequality and exploitation. The caste system degenerated Dalit lifes into pathogenic condition where occupations changed into castes.

For centuries, Dalits were excluded from the mainstream society and were only allowed to pursue menial occupations like cleaning dry latrines, sweeping etc.They lived in the Hindu villages hence did not have advantage of geographical isolation like tribes. They were pushed to the outer areas of villages whereas, the mainland was occupied by the Brahmins. They were barred from entering into those mainland areas in every sense, they were prohibited to wear decent dress and ornaments besides being untouchable.

Many of the atrocities were committed in the name of religion. Besides, the system of Devadasi they poured molten lead into the ears of a Dalit, who happened to listen to some mantra. To retain the stronghold on people, education was monopolized.The most inhuman practice is that of untouchability, which made the Dalits to live in extreme inhuman situations . This has made the Dalits to rise and protest, against the inhuman practices of Brahmanism .The Dalits began their movement in India with their basic demand for equality.

The Dalit movement that gained momentum in the post independence period, have its roots in the Vedic period. It was to the Shramanic -Brahmanic confrontation and then to the Bhakti Movement.

With the introduction of western language, and with the influence of the Christian missionaries, the Dalits began to come across the ideals of equality and liberty and thus began the Dalit Movement in modern times. The frustrated Dalit minds when mixed with reason began confrontation against the atrocities of Brahmanism.

Dalit movement was fundamentally the movement to achieve mobility on part of the groups which has logged behind. They were a reaction against the social, cultural and economic preponderance and exclusiveness of other class over them.

Educated Dalit , gradually begin to talk about the problems of poor and about exploitation and humiliations from the upper castes. They also got a fillip through British policy of divide and rule in which census operation played a sufficient role (British policy of classifying caste). This provided an opportunity for making claims for social pre-eminence through caste mobilisation. Improved communication network made wider links and combination possible; new system of education provided opportunity for socio-economic promotion, new administrative system, rule of law undermined certain privileges enjoyed by few and certain economic forces like industrialization threw open equal opportunities for all dismantling social barriers.

All these factors contributed to the shift in position of untouchables. Social reform movement such as those of Jyotiba phule in Maharashtra and Sri Narayan Guru in Kerala also began to question caste inequality. Gandhiji integrated the issue of abolition of untouchability into national movement and major campaign and struggles such as Varkom and Guruvayur Satyagrahawere organized.

Gandhiji’s effort was to make upper caste realise severity of injustice done via practice of untouchability.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar emerged as major leader of Depressed Classes by late 1920’s. He formed All Indian Scheduled Caste Federation in 1942. He also cooperates with colonial government on understanding that he could get more benefits for SCs. The All India S.C. Federation also contested election, but its candidates lost to Congress.

Others strands also emerged in different regions in Punjab the Adi Dharm, in U.P.the Adi Hindi and in Bengal the Namashvedsas.

In Bihar, Jagjivan Ram who emerged as the most important Congress leader formed Khetmajoor Sabha and Depressed Class League. In early 1970’s a new trend identified as Dalit Panthers merged in Maharashtra as a part of country wide wave of radical politics. The Dalit Panthers learned ideologically to Ambedkar’s thought. By 1950’s Dalit Panther had developed serious differences and the party split up and declined.

In North India new party BSP emerged in 1980’s under Kanshi Ram and later Mayawati who became the chief minister of U.P.

Acharya Ishvardatt Medharthi (1900–1971) of Kanpur supported the cause of the Dalits. He studied Pali at Gurukul Kangri and Buddhist texts were well known to him. He was initiated into Buddhism by Gyan Keto and the Lokanatha in 1937. Gyan Keto (1906–1984), born Peter Schoenfeldt, was a German who arrived in Ceylon in 1936 and became a Buddhist. Medharthi strongly criticised the caste system in India. He claimed that the Dalits (“Adi Hindus”) were the ancient rulers of India and had been trapped into slavery by Aryan invaders.

Dynamics of Dalit Movement: Sanskritization

The strategies, ideologies, approaches of Dalit movement varied from leader to leader, place to place and time to time.

Thus, some Dalit leaders followed the process of ’Sanskritization’ to elevate themselves to the higher position in caste hierarchy. They adopted Brahman manners, including vegetarianism, putting sandalwood paste on forehead, wearing sacred thread, etc. Thus Dalit leaders like Swami Thykkad (Kerala), Pandi Sunder Lai Sagar (UP), Muldas Vaishya (Gujarat), Moon Vithoba Raoji Pande (Maharashtra) and others tried to adopt established cultural norms and practices of the higher castes. Imitation of the high caste manners by Dalits was an assertion of their right to equality.

Adi-Hindu movement

Treating Dalits as outside the fourfold Varna system, and describing them as ‘outcastes’ or ‘Panchama’ gave rise to a movement called Adi-Hindu movement. Thus, certain section of Dalit leadership believed that Dalits were the original inhabitants of India and they were not Hindus. That Aryans or Brahmins who invaded this country forcibly imposed untouchability on the original inhabitants of this land. They believed that if Hinduism was discarded, untouchability would automatically come to an end.

That Dalits began to call themselves Adi-Andhras in Andhra, Adi- Karnataka in Karnataka, Adi-Dravidas in Tamil Nadu, Adi-Hindus in Uttar Pradesh and Adi-Dharmis in Punjab. Dalits also followed the route of conversion with a purpose of getting rid of untouchability and to develop their moral and financial conditions.

Conversions

A good number of Dalits were converted to Christianity, especially in Kerala. Some of the Dalits, especially in Punjab were converted to Sikhism. They are known asMazhabis, Namdharis, Kabir Panthis etc.

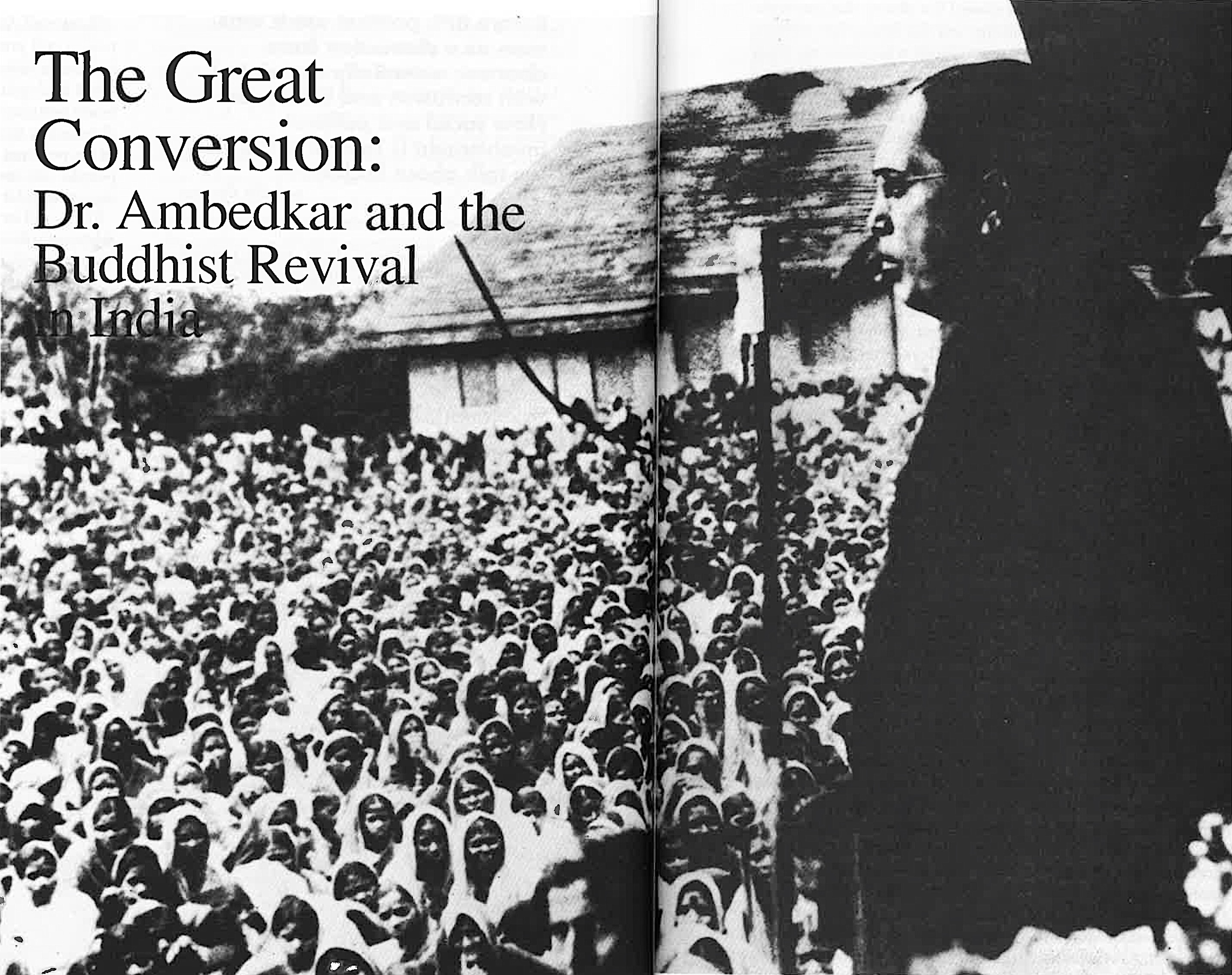

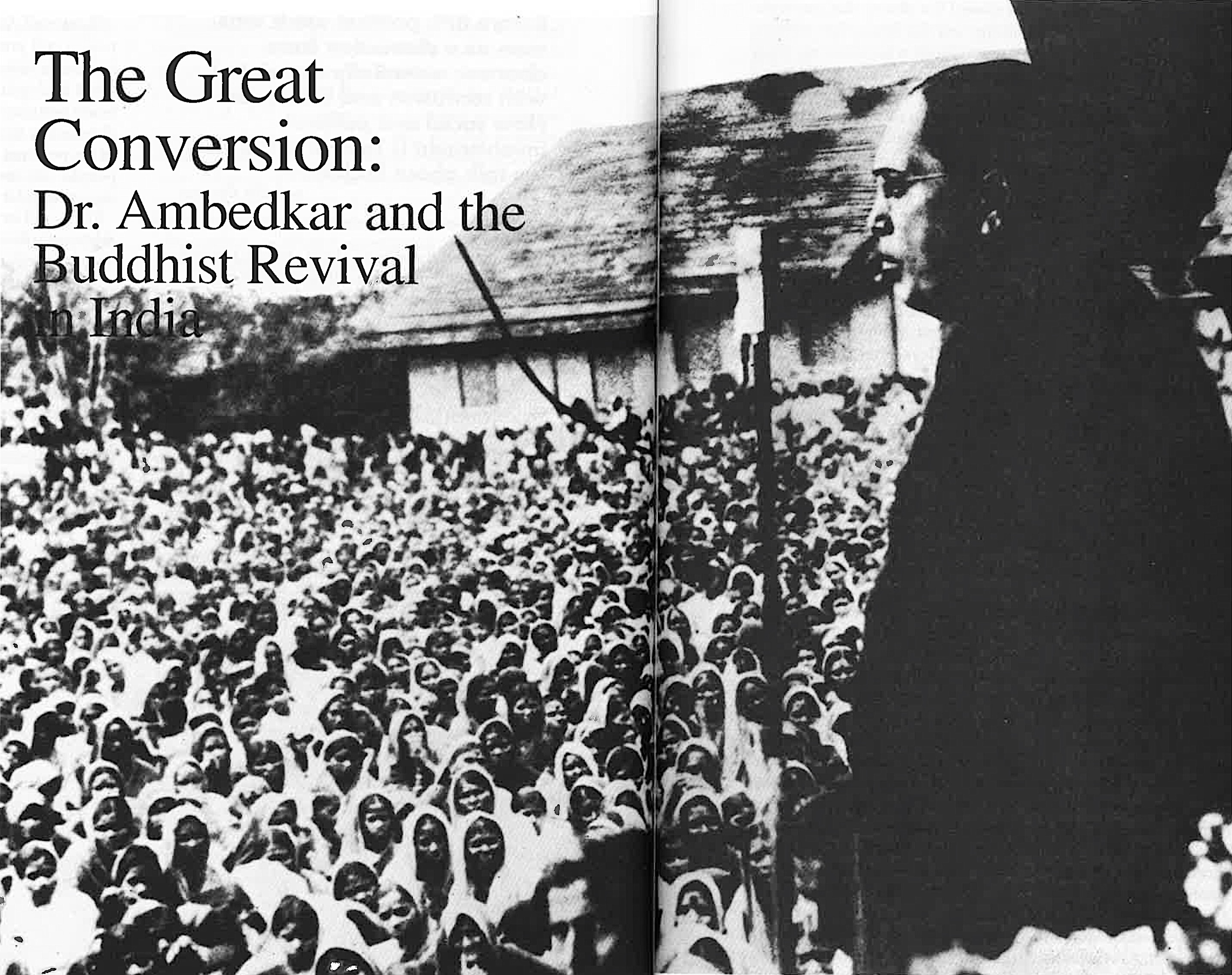

Dalits also got converted to Buddhism. Dr. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism along with his millions of followers at Nagpur in 1956.

Finding Sects

As a protest against Hinduism some of the Dalit leaders founded their own sects or religions. Guru Ghasi Das (MP) founded Satnami Sect. Gurtichand Thakur (Bengal) founded Matua Sect. Ayyan Kali (kerala) founded SJPY (Sadha Jana Paripalan Yogam) and Mangu Ram (Panjab) founded Adi Dharam.

Ambedkar’s activism

Attempts were also made to organize Dalits politically in order to fight against socio-economic problems. Dr. Ambedkar formed the Independent Labour Party in 1936. He tried to abolish the exploitative Khoti system prevailing in Kokan part of Maharashtra, and Vetti or Maharaki system (a wage free hereditary service to the caste Hindus in the local administration). He tried to convince the Government to recruit the Mahars in Military. Ultimately he became successful in 1941 when the first Mahar Regiment was formed.

With the growing process of democratization, Dr. Ambedkar demanded adequate representation for Dalits in the legislatures and in the administration. Government of India Act, 1919, provided for one seat to the depressed classes in the central Legislative Assembly. In 1932, British Government headed by Ramsoy Macdonald announced the ‘Communal Award’. The award envisaged separate electorate for the Depressed Classes. Mahatma Gandhi went on a historic fast in protest against Communal Award especially in respect of depressed classes. The issue was settled by Poona Pact, September 1932. It provided for reservation of seats for depressed classes out of general electorates sets. The Constitution of India now provides for reservation of seats for Scheduled Castes

in proportion to their population in Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha under Article 330 and 332.

Dalit Literary Movement

At a time, when there was no means of communication to support the Dalits, pen was the only solution. The media, newspapers were all under the control of the powerful class – the Brahmins. Given that the Brahmins would never allow the Dalits voice to be expressed, as it would be a threat for their own survival, the Dalits began their own magazine and began to express their own experiences.

Dalit literature, the literature produced by the Dalit consciousness, emerged initially during the Mukti movement. Later, with the formation of the Dalit Panthers, there began to flourish a series of Dalit poetry and stories depicting the miseries of the Dalits the roots of which lies in the rules and laws of Vedas and Smritis. All these literature argued that Dalit

Movement fights not only against the Brahmins but all those people whoever practices exploitation, and those can be the Brahmins or even the Dalits themselves.

New revolutionary songs, poems , stories , autobiographies were written by Dalit writers. All their feelings were bursting out in the form of writings.

Educated Dalit and intellectuals begin to talk about the problems without any hesitation and tried to explain to the other illiterate brothers about the required change in the society. Dalit literature tried to compare the past situation of Dalits to the present and future generation not to create hatred, but to make them aware of their pitiable condition.

Power as Means to Attain Dignity

Power can be cut by only power. Hence, to attain power, the first thing required is knowledge. It was thus, Phule and Ambedkar gave the main emphasis on the education of the Dalits, which will not only bestow them with reason and judgement capacity, but also political power, and thereby socio—economic status and a life of dignity. They knew that the political strategy of gaining power is either an end in itself or a means to other ends. In other words, if the Dalits have power, then they do not have to go begging to the upper castes.

Also they will get greater economic and educational opportunities. The upper castes enjoy social power, regardless of their individual circumstances with respect to their control over material resources, through their linkages with the other caste fellows in the political system –in the bureaucracy , judiciary and legislature. And so , the Dalits require power to control the economic scenario and thereby the politics of the country.

Phule thus added that without knowledge, intellect was lost; without intellect, morality was lost; without morality, dyna- mism was lost; without dynamism, money was lost; without money Shudras were degraded, all this misery and disaster were due to the lack of knowledge. Inspired by Thomas Paine‘s ―”The rights of Man”, Phule sought the way of education which can only unite the Dalits in their struggle for equality.

The movement was carried forward by Ambedkar who contested with Gandhi to give the Dalits, their right to equality. In the words of Ambedkar, Educate, Organize and agitate. Education, the major source of reason, inflicts human mind with extensive knowledge of the world, whereby, they can know the truth of a phenomena, that is reality. It therefore, would help to know the truth of Brahmanism in Indian society, and will make them to agitate against caste based inhuman practices. Only when agitation begin, in the real sense, can the

Dalit be able to attain power and win the movement against exploitation. Gandhis politics was unambigously centring around the defence of caste with the preservation of social order in Brahmanical pattern. He was fighting for the rights of Dalits but was not ready for inter-caste marriage.

Post-Independent Dalit Movements B.R. Ambedkar and Buddhist dalit Movement

Babasaheb Ambedkar has undoubtedly been the central figure in the epistemology of the dalit universe. It is not difficult to see the reason behind the obeisance and reverence that dalits have for Ambedkar. They see him as one who devoted every moment of his life thinking about and struggling for their emancipation; who sacrificed all the comforts and conveniences of life that were quite within his reach to be on their side; who conclusively disproved the theory of caste based superiority by rising to be the tallest amongst the tall despite enormous odds, and finally as one who held forth the torch to illuminate the path of their future.

Upon India’s Transfer of Power by British Government on 15 August 1947, the new Congress-led government invited Ambedkar to serve as the nation’s first Law Minister, which he accepted. On 29 August, he was appointed Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee, charged by the Assembly to write India’s newConstitution.The text prepared by Ambedkar provided constitutional guarantees and protections for a wide range of civil liberties for individual citizens, including freedom of religion, the abolition of untouchability and the outlawing of all forms of discrimination. Ambedkar argued for extensive economic and social rights for women, and also won the Assembly’s support for introducing a system of reservations of jobs in the civil services, schools and colleges for members of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, a system akin to affirmative action. India’s lawmakers hoped to eradicate the socio-economic inequalities and lack of opportunities for India’s depressed classes through these measures.

Ambedkar resigned from the cabinet in 1951 following the stalling in parliament of his draft of the Hindu Code Bill, which sought to expound gender equality in the laws of inheritance and marriage. Ambedkar independently contested an election in 1952 to the lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha, but was defeated in the Bombay constituency by a little-known Narayan Sadoba Kajrolkar. He was appointed to the upper house, of parliament, the Rajya Sabha in March 1952 and would remain as member till death.

Conversion to Buddhism

Ambedkar had considered converting to Sikhism, which saw oppression as something to be fought against and which for that reason appealed also to other leaders of scheduled castes. He rejected the idea after meeting with leaders of the Sikh community and concluding that his conversion might result in him having a “second-rate status” among Sikhs. He studied Buddhism all his life, and around 1950, he turned his attention fully to Buddhism and travelled to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to attend a meeting of the World Fellowship of Buddhists. While dedicating a new Buddhist vihara near Pune, Ambedkar announced that he was writing a book on Buddhism, and that as soon as it was finished, he planned to make a formal conversion to Buddhism.

Ambedkar twice visited Burma in 1954; the second time in order to attend the third conference of the World Fellowship of Buddhists in Rangoon.In 1955, he founded theBharatiya Bauddha Mahasabha. He completed his final work, The Buddha and His Dhamma, in 1956. It was published posthumously. After meetings with the Sri Lankan Buddhist monk Saddhatissa, Ambedkar organised a formal public ceremony for himself and his supporters in Nagpur on 14 October 1956. Ambedkar completed his own conversion, along with his wife. He then proceeded to convert some 500,000 of his supporters who were gathered around him. He then travelled to Kathmandu in Nepal to attend the Fourth World Buddhist Conference. His work on The Buddha or Karl Marx and “Revolution and counter-revolution in ancient India” remained incomplete.

His allegation of Hinduism foundation of caste system, made him controversial and unpopular among the Hindu community. His conversion to Buddhism sparked a revival in interest in Buddhist philosophy in India and abroad. Ambedkar’s political philosophy has given rise to a large number of political parties, publications and workers’ unions that remain active across India, especially in Maharashtra.

The Buddhist movement was somewhat hindered by Dr. Ambedkar’s death so shortly after his conversion. It did not receive the immediate mass support from the Untouchable population that Ambedkar had hoped for. Division and lack of direction among the leaders of the Ambedkarite movement have been an additional impediment. According to the 2001 census, there are currently 7.95 million Buddhists in India, at least 5.83 million of whom are Buddhists in Maharashtra.This makes Buddhism the fifth-largest religion in India and 6% of the population of Maharashtra, but less than 1% of the overall population of India.TheBuddhist revival remains concentrated in two states: Ambedkar’s native Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh — the land of Acharya Medharthi and their associates.

Acharya Medharthi retired from his Buddhapuri school in 1960, and shifted to an ashram in Haridwar. He turned to the Arya Samaj and conducted Vedic yajnas all over India. His follower, Bhoj Dev Mudit, converted to Buddhism in 1968 and set up a school of his own.

Rajendranath Aherwar appeared as an important Dalit leader in Kanpur. He joined the Republican Party of India and converted to Buddhism along with his whole family in 1961. In 1967, he founded the Kanpur branch of “Bharatiya Buddh Mahasabha”.

The Dalit Buddhist movement in Kanpur gained impetus with the arrival of Dipankar, a Chamar bhikkhu, in 1980. Dipankar had come to Kanpur on a Buddhist mission and his first public appearance was scheduled at a mass conversion drive in 1981. The event was organised by Rahulan Ambawadekar, an RPI Dalit leader. In April 1981, Ambawadekar founded the Dalit Panthers (U.P. Branch) inspired by the Maharashtrian Dalit Panthers.

Dalit Panthers

Dalit Panther as a social organization was founded by Namdev Dhasal in April 1972 in Mumbai, which saw its heyday in the 1970s and through the 80s. Dalit Panther is inspired by Black Panther Party, a revolutionary movement amongst African-Americans, which emerged in the United States and functioned from 1966-1982.The name of the organization was borrowed from the ‘Black Panther’ Movement of the USA. They called themselves “Panthers” because they were supposed to fight for their rights like panthers, and not get suppressed by the strength and might of their oppressors.

The US Black Panther Party always acknowledged and supported the Dalit Panther Party through the US Black Panther Newspaper which circulated weekly throughout the world from 1967-1980. Its organization was modelled after the Black Panther. The members were young men belonging to Neo-Buddhists and Scheduled Castes. Most of the leaders were literary figures

.The controversy over the article “Kala Swatantrata Din”

(Black Independence Day) by Dhale which was published in “Sadhana” in 1972 created a great sensation and publicised the Dalit Panthers through Maharashtra. The Panther’s full support to Dhale during this controversy brought Dhale into the movement and made him a prominent leader. With the publicity of this issue through the media, Panther branches sprang up spontaneously in many parts of Maharashtra. The Dalit Panther movement was a radical departure from earlier Dalit movements. Its initial thrust on militancy through the use of rustic arms and threats, gave the movement a revolutionary colour. Going by their manifesto, dalit panthers had broken many new grounds in terms of radicalising the political space for the dalit movement. They imparted the proletarian – radical class identity to dalits and linked their struggles to the struggles of all oppressed people over the globe. The clear cut leftist stand reflected by this document undoubtedly ran counter to the accepted legacy of Ambedkar as projected by the various icons, although it was sold in his name as an awkward tactic.

The pathos of casteism integral with the dalit experience essentially brought in Ambedkar, as his was the only articulate framework that took cognisance of it. But, for the other contemporary problems of deprivations, Marxism provided a scientific framework to bring about a revolutionary change. Although, have-nots from both dalits and non-dalits craved for a fundamental change, the former adhered to what appeared to be Ambedkarian methods of socio-political change and the latter to what came to be the Marxian method which tended to see every social process as the reflection of the material reality. Both caused erroneous interpretations. It is to the credit of Panthers that the assimilation of these two ideologies was attempted for the first time in the country but unfortunately it proved abortive in absence of the efforts to rid each of them of its obfuscating influence and stress their non-contradictory essence. Neither, there was theoretical effort to integrate these two ideologies, nor was there any practice combining social aspects of caste with say, the land question in the village setting. This ideological amalgam could not be acceptable to those under the spell of the prevailing Ambedkar-icons and therefore this revolutionary seedling in the dalit movement died a still death.

The reactionaries objected to the radical content of the programme alleging that the manifesto was doctored by the radicals – the Naxalites. There is no denying the fact that the Naxalite movement which had erupted quite like the Dalit Panther, as a disenchantment with and negation of the established politics, saw a potential ally in the Panthers and tried to forge a bond right at the level of formulation of policies and programme of the latter. But even if the Panthers had chosen to pattern their programme on the ten-point programme of the Black Panther Party (BPP) in the USA, which had been the basic inspiration for their formation, it would not have been any less radical.The amount of emphasis on the material aspects of life that one finds in the party programme of the BPP could still have been inimical to the established icon of Ambedkar.

Radicalism was the premise for the very existence of the Dalit Panther and hence the quarrel over its programme basically reflected the clash between the established icon of Ambedkar and his radical version proposed in the programme. The fact that for the first time the Dalit Panther exposed dalits to a radical Ambedkar and brought a section of dalit youth nearer to accepting it certainly marks its positive contribution to the dalit movement.

There were material reasons for the emergence of Dalit Panthers. Children of the Ambedkarian movement had started coming out of universities in large numbers in the later part of 1960s, just to face the blank future staring at them. The much-publicised Constitutional provisions for them turned out to be a mirage. Their political vehicle was getting deeper and deeper into the marsh of Parliamentarism. It ceased to see the real problems of people. The air of militant insurgency that had blown all over the world during those days also provided them the source material to articulate their anger.

Unfortunately, quite like the BPP, they lacked the suitable ideology to channel this anger for achieving their goal. Interestingly, as they reflected the positive aspects of the BPP’s contributions in terms of self-defence, mass organising techniques, propaganda techniques and radical orientation, they did so in the case of BPP’s negative aspects too. Like Black Panthers they also reflected ‘TV mentality’ (to think of a revolutionary struggle like a quick-paced TV programme), dogmatism, neglect of economic foundation needed for the organisation, lumpen tendencies, rhetoric outstripping capabilities, lack of clarity about the form of struggle and eventually corruptibility of the leadership. The Panthers’ militancy by and large remained confined to their speeches and writings.

One of the reasons for its stagnation was certainly its incapability to escape the petit bourgeois ideological trap built up with the icons of Ambedkar. It would not get over the ideological ambivalence represented by them. Eventually, the petit-bourgeoise ‘icon’ of Ambedkar prevailed and extinguished the sparklet of new revolutionary challenge. It went the RPI (founded by Ambedkar) way and what remained of it were the numerous fractions.

The Dalit Panther phase represented the clash of two icons: one, that of a radical ‘Ambedkar’, as a committed rationalist, perpetually striving for the deliverance of the most oppressed people in the world. He granted all the freedom to his followers to search out the truth using the rationalist methodology as he did. The other is of the ‘Ambedkar’ who has forbidden the violent methods and advocated the constitutional ways for his followers, who was a staunch anti-Communist, ardent

Buddhist. As it turned out, the radical icon of Ambedkar was projected without adequate conviction. There was no one committed to propagating such an image of Ambedkar, neither communists nor dalits. Eventually it remained as a veritable hodgepodge.

Phenomenon of Kanshiram and Mayawati (Bahujan Samajwadi Party)

In 1971 Kansiram quit his job in DRDO and together with his colleagues established the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes and Minorities Employees Welfare Association.Through this association, attempts were made to look into the problems and harassment of the above-mentioned employees and bring out an effective solution for the same. Another main objective behind establishing this association was to educate and create awareness about the caste system. This association turned out to be a success with more and more people joining it.

In 1973, Kanshi Ram again with his colleagues established the BAMCEF: Backward And Minority Communities Employees Federation. The first operating office was opened in Delhi in 1976 with the motto-“Educate Organize and Agitate“.

This served as a base to spread the ideas of Ambedkar and his beliefs. From then on Kanshi Ram continued building his network and making people aware of the realities of the caste system, how it functioned in India and the teachings of Ambedkar.

In 1980 he created a road show named “Ambedkar Mela” which showed the life of Ambedkar and his views through pictures and narrations. In 1981 he founded theDalit Soshit

Samaj Sangharsh Samiti or DS4 as a parallel association to the BAMCEF. It was created to fight against the attacks on the workers who were spreading awareness on the caste system. It was created to show that workers could stand united and that they too can fight. However this was not a registered party but an organization which was political in nature. In 1984, he established a full-fledged political party known as the Bahujan Samaj Party. However, it was in 1986 when he declared his transition from a social worker to a politician by stating that he was not going to work for/with any other organization other than the Bahujan Samaj Party. Later he converted to Buddhism.

The movement of Kanshiram markedly reflected a different strategy, which coined the ‘Bahujan’ identity encompassing all the SCs, STs, BCs, OBCs and religious minorities than ‘dalit’, which practically represented only the scheduled castes. Kanshiram started off with an avowedly apolitical organisation of government employees belonging to Bahujana, identifying them to be the main resource of these communities. It later catalysed the formation of an agitating political group creatively coined as DS4, which eventually became a full-fledged political party – the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP).

Purely, in terms of electoral politics, which has somehow become a major obsession with all the dalit parties, Kanshiram’s strategy has proved quite effective, though in only certain parts of the country. He has given a qualitative impetus to the moribund dalit politics, locating itself into a wider space peopled by all the downtrodden of India. But he identified these people only in terms of their castes and communities. It may be said to his credit that he reflected the culmination of what common place icon of Ambedkar stood for.

Kanshiram shrewdly grasped the political efficacy of this icon that sanctioned the pursuit of power in the name of downtrodden castes. The religious minorities which potentially rears the sense of suffering marginalisation from the majority community could be easily added to it to make a formidable constituency in parliamentary parlance. Every one knew it but none knew how to implement. Kanshiram has seemingly succeeded in this task at least in certain pockets.

The careful analysis will show that the combination of certain historical developments and situational factors has been behind this success. As Kanshiram has amply experienced, it is not replicable elsewhere. It is bound to be short-lived and illusory unless this success is utilised to implement a revolutionary programme to forge a class identity among its constituents. If not, one will have to constantly exert to recreate the compulsions for their togetherness and allegiance. In absence of any class-agenda, which is certainly the case of BSP, these compulsions could only be created through manipulative politics for which political power is an essential resource. BSP’s unprincipled pursuit of power is basically driven by this exigency. It is futile to see in this game a process of empowerment of the subject people as could be seen from the statistical evidence of the cases of atrocities, and of overall situation of the poor people under its rule.

The imperatives of this kind of strategy necessarily catapult the movement into the camp of the ruling classes as has exactly happened with BSP. BSP’s electoral parleys with Congress, BJP, Akali Dal (Mann) that reached the stage of directly sharing State power in UP recently, essentially reflect this process of degeneration and expose its class characteristics today. It seems to have sustaining support from the icon that BSP itself created, where Ambedkar was painted as the intelligent strategist who could turn any situation to his advantage, who used every opportunity to grab political power to achieve his objective.

Kanshiram’s reading of Ambedkar ignores the fact that Ambedkar had to carve out space for his movement in the crevices left by the contradictions between various Indian political parties and groups on one side and the colonial power on the other. For most of his time, he sought maximisation of this space from the contending Muslim League and Congress, and eventually brought dalit issue to the national political agenda.

Kanshiram stuffs his Ambedkar icon entirely with such kind of superfluity that it would look credible to the gullible dalit masses. This icon approves of his sole ideology that political power to his party could solve all dalit problems. He did not care for democracy. To some extent this non-democratic stance spells his compulsions to have unitary command over his party structure as without it, his adversaries would gobble it up. He did not have any utility for any programme or manifesto, his sole obsession is to maximise his power by whatever means. In the rhetoric of empowering Bahujans, he does not even feel it necessary to demonstrate what exactly this empowering means and what benefits it would entail them.

The obsession with capturing power robbed him of certain fundamental values that Ambedkar never compromised. The underlying value of the movement of Ambedkar was represented by liberty, equality and fraternity. Kanshiram does not seem to respect any value than the political and money power.

For Ambedkar political power was a means, to Kanshiram it appears to be the end. Notwithstanding these broad differences, he has succeeded in luring the dalit masses in certain pockets of the country by projecting an Ambedkar icon that sanctioned his unscrupulous pursuits of power. The crux of Kanshiram can be traced to his superfluous attempt to replicate Ambedkar’s movement of 1920s. When

Ambedkar realised the potency of political power, he launched his Indian Labour Party that reflected his urge to bring together the working class, transcending the caste lines. It is only when the political polarisation took communal turn that he abandoned his ILP project and launched the Scheduled Caste

Federation. Ambedkar joined hands with a few political parties – one the communists (while joining the strike of mill workers) and the other is thePraja Samajwadi Party of Ashok Mehta in the 1952 elections. Although, he accepted the Congress support and offered to work in their government, he never tied up his political outfit to the Congress. Kanshiram’s

record so far clearly shows that he is ready to join hands with

any one promising him the share of political power. Ambedkar pointed at the capitalism and Brahminism as the twin enemy for his movement but Kanshiram enthusiastically embraced them.

Apart from these broad political trends, there are many regional outfits like Dalit Mahasabha in Andhra Pradesh, Mass Movement in Maharashtra, Dalit Sena in Bihar and elsewhere, etc., some of which dabble directly into electoral politics and some of them do not. So far, none of them have a radically different icon of Ambedkar from the ones described above. They offer some proprietary ware claiming to be a shade better than that of others.

Did State really helped?

The post-1947 State, which has never tired of propagandising its concern for dalits and poor, has in fact been singularly instrumental in aggravating the caste problem with its policies. Even the apparently progressive policies in the form of Land Ceiling Act, Green Revolution, Programme of Removal of Poverty, Reservations to Dalits in Services and Mandal Commission etc. have resulted against their professed objectives.

The effect of the Land Ceiling Act, has been in creating a layer of the middle castes farmers which could be consolidated in caste terms to constitute a formidable constituency. In its new incarnation, this group that has traditionally been the immediate upper caste layer to dalits, assumed virtual custody of Brahminism in order to coerce dalit landless labourers to serve their socio-economic interests and suppress their assertive expression in the bud. The Green Revolution was the main instrument to introduce capitalisation in agrarian sector. It reinforced the innate hunger of the landlords and big farmers for land as this State sponsored revolution produced huge surplus for them. It resulted in creating geographical imbalance and promoting unequal terms of trade in favour of urban areas. Its resultant impact on dalits has been far more excruciating than that of the Land Ceiling Act.

The much publicised programme for Removal of Poverty has aggravated the gap between the heightened hopes and aspirations of dalits on one hand and the feelings of deprivation among the poorer sections of non-dalits in the context of the special programmes especially launched for upliftment of dalits. The tension that ensued culminated in increasingly strengthening the caste – based demands and further aggravating the caste – divide.

The reservations in services for dalits, notwithstanding its benefits, have caused incalculable damage in political terms. Reservations created hope, notional stake in the system and thus dampened the alienation; those who availed of its benefit got politically emasculated and in course consciously or unconsciously served as the props of the system. The context of scarcity of jobs provided ample opportunity to reactionary forces to divide the youth along caste lines. Mandal Commission, that enthused many progressive parties and people to upheld its extension of reservation to the backward castes, has greatly contributed to strengthen the caste identities of people. In as much as it empowers the backward castes, actually their richer sections, it is bound to worsen the relative standing of dalits in villages.

Dalits and Contemporary Indian Politics:

While the Indian Constitution has duly made special provisions for the social and economic uplift of the Dalits, comprising the scheduled castes and tribes in order to enable them to achieve upward social mobility, these concessions are limited to only those Dalits who remain Hindu. There is a demand among the Dalits who have converted to other religions that the statutory benefits should be extended to them as well, to overcome and bring closure to historical injustices. Another major politically charged issue with the rise of Hindutva’s (Hindu nationalism) role in Indian politics is that of religious conversion. This political movement alleges that conversions of Dalits are due not to any social or theological motivation but to allurements like education and jobs. Critics argue that the inverse is true due to laws banning conversion, and the limiting of social relief for these backward sections of Indian society being revoked for those who convert. Many

Dalits are also becoming part of Hindutva ideology. Another political issue is over the affirmative-action measures taken by the government towards the upliftment of Dalits through quotas in government jobs and university admissions. The seats in the National and State Parliaments are reserved for Scheduled Caste and Tribe candidates, a measure sought by B. R. Ambedkar and other Dalit activists in order to ensure that Dalits would obtain a proportionate political voice. Anti-Dalit prejudices exist in fringe groups, such as the extremist militia Ranvir Sena, largely run by upper-caste landlords in areas of the Indian state of Bihar. They oppose equal or special treatment of Dalits and have resorted to violent means to suppress the Dalits.

A dalit, Babu Jagjivan Ram became Deputy Prime Minister of India In 1997, K. R. Narayanan was elected as the first Dalit President. K. G. Balakrishnan became first Dalit Chief Justice of India. In 2007, Mayawati, a Dalit, was elected as the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India. Some say that her 2007 election victory was due to her ability to win

support from Dalits and the Brahmins. However, Caste loyalties were not necessarily the voters’ principal concern. Instead, inflation and other issues of social and economic development were the top priorities of the electorate regardless of caste.

Dalit who became chief Ministers in India are Damodaram Sanjivayya (Andhra Pradesh) , Mayawati four times chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, Jitan Ram Manjhi, chief minister of Bihar.

Some Dalits have been successful in business and politics of modern India. Despite anti-discrimination laws, many Dalits still suffer from social stigma and discrimination. Ethnic tensions and caste-related violence between Dalit and non-Dalits have been witnessed. The cause of such tensions is claimed to be from economically rising Dalits and continued prejudices against Dalits.

References

1. Dalit – The Black Untouchables of India, by V.T. Rajshekhar. 2003 – 2nd

print, Clarity Press, Inc. ISBN 0-932863-05-1.

2. Untouchable!: Voices of the Dalit Liberation Movement, by Barbara R.

Joshi, Zed Books, 1986. ISBN 0-86232-460-2, ISBN 978-0-86232-460-5.

3. Dalits and the Democratic Revolution – Dr. Ambedkar and the Dalit

Movement in Colonial India, by Gail Omvedt. 1994, Sage Publications. ISBN 81-7036-368-3.

4. The Untouchables: Subordination, Poverty and the State in Modern

India, by Oliver Mendelsohn, Marika Vicziany, Cambridge University Press,

1998, ISBN 0-521-55671-6, ISBN 978-0-521-55671-2.

5. Dalit Identity and Politics, by Ranabira Samaddara, Ghanshyam Shah,

Sage Publications, 2001. ISBN 0-7619-9508-0, ISBN 978-0-7619-9508-1.

6. Journeys to Freedom: Dalit Narratives, by Fernando Franco, Jyotsna

Macwan, Suguna Ramanathan. Popular Prakashan, 2004. ISBN 81-85604-

65-7, ISBN 978-81-85604-65-7.

7. Towards an Aesthetic of Dalit Literature, by Sharankumar Limbale.

2004, Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2656-8.

8. From Untouchable to Dalit – Essays on the Ambedkar Movement,

by Eleanor Zelliot. 2005, Manohar. ISBN 81-7304-143-1.

9. Dalit Politics and Literature, by Pradeep K. Sharma. Shipra Publications,

2006. ISBN 81-7541-271-2, ISBN 978-81-7541-271-2.

10. Dalit Visions: The Anti-caste Movement and the Construction of an Indian Identity, by Gail Omvedt. Orient Longman, 2006. ISBN 81-250-2895-

1, ISBN 978-81-250-2895-6.

11. Dalits in Modern India – Vision and Values, by S M Michael. 2007, Sage

Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-3571-1.

12. Dalit Literature : A Critical Exploration, by Amar Nath Prasad & M.B. Gaijan. 2007.ISBN 81-7625-817-2.

13. Debrahmanising History : Dominance and Resistance in Indian Society,

by Braj Ranjan Mani. 2005. ISBN 81-7304-640-9. Manohar Publishers and

Distributors

Hindutva challenge to radical traditions and “little histories” that underlay anti-caste movement in Kerala

Meera Velayudhan*, a senior researcher, writes that the recent invite to Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi is a sure way to erode the ‘little histories’ that underlay the roots of equality, both as a concept and as engagement by oppressed castes, in particular, former agrestic slaves and in what may be considered as the beginnings of radicalization in modern Kerala. It is also part of an ongoing attempt to bring all subaltern castes into the fold of Hindutva

According to Brahmanical myths, Kerala, the land, was reclaimed from the sea, after Parashurama, an avatar of Maha Vishnu, threw its battle axe into the sea. Unlike the Ayodhya myth (built on the edifice of a demolished Babri masjid and the spate of communal violence that followed the Rath Yatra), the saffron brigade – the Hindu aikya vedi – had been unable to create a similar context in Kerala. However, political equations are changing. The SNDP-NSS Alliance (known as Hindu Grand Alliance of the once warring Nair Service Society (NSS) of the upper caste Nairs and Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalanayogam (SNDP) of the OBC Ezhavas) marked a step forward for the saffron agenda. A new entrant in the scene, Namo, or Narendra Modi, be it through his visit to Santhigiri, the invite extended to Modi by Kerala Pulayar Mahajana Sabha, point to the challenges of the times and the dangers ahead.

This article is written in the context of the invite sent by the Kerala Pulayar Mahajana Sabha to Narendra Modi, who turned Gujarat into the laboratory in 2002 to test BJP’s Hindutva agenda through unprecedented communal violence witnessed in south asia post independence. That the invite is for addressing a mass rally in Alwaye in February 2014 to commemorate 100 years of the founding of the Pulaya Mahajana Sabha (Cochin) is all the more shocking and a travesty of history – earlier in 1993, the Kerala Pulayar Mahajana Sabha had protested the demotion of the Babri Masjid as an attack on India’s secular fabric and called for protection of religious rights and harmony.

This invite to Narendra Modi is a sure way to erode the ‘little histories’ that underlay the roots of equality, both as a concept and as engagement by oppressed castes, in particular, former agrestic slaves and in what may be considered as the beginnings of radicalization in modern Kerala. It is also part of an ongoing attempt to bring all subaltern castes into the fold of Hindutva.

Drawing from parts of the forthcoming autobiographical writings of the author’s mother, Dakshayani Velayudhan, this article seeks to highlight the background of the formation of the Pulaya Mahajana Sabha by members of her family in 1913 in Bolghatty, Cochin. Also cited are efforts in the early 1900 at building similar organizations in the face of strong, often violent, opposition from dominant castes and communities.

The Pulaya Mahajana Sabha – Cochin (1913)

In her autobiography, Dakshayani Velayudhan (1912-1978) (a parliamentarian belonging to the depressed classes, she belonged to Pulaya community and was the only Dalit woman member of the Constituent Assembly of India) writes:

“My elder two brothers and my father Kunjan’s younger brother, Krishnethi (Krishnadiyasan 1877-1937), Pt Karruppan (Prof Mahrajas College), TK Krishna Menon (from the Thottekal family which produced several Dewans) formed the Pulaya Mahajan Sabha, with Krishnethi as President. The meeting was held with country boats tied together in the sea in Bolghatty – the sea did not have a caste In Kochi, the untouchables were not allowed to hold a meeting “in my land” by the Maharaja. The raft was made by joining together a large number of catamarans with the help and support of the fisherfolk. Later Krishnaadi told the Maharaja that ‘he did not disobey the order of His Highness’ to hold a meeting in his ‘land’. The Pulaya Mahajana Sabha took up social issues. My elder brothers were the first to crop their long hair and wear shirts. Abuses were showered on them and also stones thrown by dominant community Latin Christians and well off Ezhavas. My brothers and Krishnethi, who worked in building the port and harbour and as petty contractors, also composed songs and poems and one song read: ‘If we go by the road, the other community roll their eyes or try to scare us, if we go by boat, they threw stones at us…” Krishnethi and others also held dialogues with various followers of Sree Narayana Guru. Earlier, an agricultural exhibition was held in Ernakulam and variety of grains displayed yet the Pulayas who were the ones who were the producers of grain were not allowed to enter Ernakulam. My brothers and Krishnethi wrote an appeal to the Cochin Maharaja in poetry form and then they were allowed entry. My mother said that she entered Ernakulam for the first time then.”

The history of the Pulaya Mahjana (Cochin) really goes back to Dakshayani’s family, Kallachammuri House also known as Nallachanmuri by branches of the family which from her father’s side had a great uncle who held the titular head ‘Ayekara Ejaman’ (given by family of Cochin Maharaja), of four ‘desams’ of the community and held seven tracts of land and households stretching from Mulavukad to Alwaye and north Parur. They followed matrilineal social customs but the menfolk were construction labour and petty contractors ( building of Wellingdon island), well versed in martial arts ( they conducted kalari schools, performed plays, composed songs, etc.), and there are many instances cited where displays of kalari are shown to be used against caste insults by either the dominant Latin Christians or landed Ezhavas in Mulavukad by Dakshayani’s father, Velutha Kunjan, a name alluding to his well built, assertive and striking personality and as an asan-teacher (had studied upto Class V), he taught Pulaya children at his house. It was indeed a unique Pulaya family history as household members were known to be well versed in Sanskrit.

In fact, Dakshayani’s father Kunjan’s younger brother, Krishnethi (Krishnadiyasan-1877-1937), was the last of the “aikara yejuman’, and with loss of joint family lands and houses through internecine family feud, worked as small contractor and worker (building of Willingdon Island, Cochin port). Krishnethi was not only a vocal critic of Hinduism but also learnt Sanskrit and music (forbidden trends) on his own.

The Pulaya Mahajana Sabha and its activities can be considered as an early form of resistance, moving from resistance in day-to-day life to bringing details of daily life into the public debates. Initially, the sabha focused on social aspects – public space and mobility, restrictions on clothes, jewellery, hair cut, etc. They composed anti-caste songs which they sang when they passed by upper castes. Stones were thrown at them by the dominant castes. Sabha lost some of its significance – both in terms of historical memory of its role, its acceptance by the community – owing to the conversion of Dakshayani’s family to Christianity – her paternal uncle Krishnethi (CK John), one of its key founders/leader, her elder brothers, KK Joseph, KK Francis, her elder sister,KK Mary and later, her mother, Maani, who became Anna. Krishnedi’s (John’s) role as a social reformer was as significant as Ayyankali’s, but lost to history owing to conversion, some historians hold. Only a study or two have been conducted on the trajectories that the Pulaya Mahjana Sabha later on. The Church in Mulavukad, now St John’s Church, was built on land donated by Krisnethi (John), land acquired following the availability of work opportunities with infrastructure development of Cochin. Although the church is now under Church of South India (CSI), it still remains a Pulaya church; the record of the history of ownership too has been changed, according to Krishnethi’s son, late Samuel and other family members, despite their protests. CSI claimed that it was mortgaged land and paid for its recovery when it was under litigation.

Ayyankali

The formation of the Pulaya Mahjana Sabha was not an isolated event. The early 1900 period saw the growth of many such organizations in different regions of Kerala. These are among the early struggles for equality and recognition. Ayyankali (1863-1941) led the anti-caste struggles for democratizing public spaces and for the rights of workers, a precursor to the formation of rural labour and working class organization in Kerala. Using a public road on a bullock cart in 1893 in Venganoor, overcoming stiff opposition from upper castes, Ayyankali next started the ‘walk for freedom’ (right to walk on public roads) to Puthen Market and at Chaliyar street facing resistance from an upper caste mob. This event inspired mass mobilization and actions in other regions such as Mannakadu, Kazhakkottam, Kaniyapuram, Parassala, Neyyantinkara, etc. These assertions led to the raising of other rights.

First and unique agrarian strike

Ayyankali next demanded the right of Pulaya children to study in schools – a move towards universalization of education. Ayyankali then started a school in 1904 to teach Pulaya children but this too was destroyed by upper castes. Despite the Travancore state passing an order opening up schools in 1907,violent opposition from upper castes, prevented the same. This led Ayyankali to give call for strike by agricultural workers to ensure education for Pulaya children-unique event in history of agrarian struggles as it was a rural protest for right to education. Ayyankali’s slogan – Educate, Organize – was also the slogan of Babsaheb Ambedkar – Educate, Organize, Struggle – later. Ayyankali warned the upper caste landlords, “If you do not allow our children to study, weeds will grow in your fields.” Other demands were added, work security (wages during off season), end to false police cases and victimization, end whipping of workers, stop practice of denial of serving tea at tea shops, rest time for workers during work hours, wages in cash, freedom of movement”.

From Kaniyapuram, Pallichal, Mudavooppara, Vizinjom, Kandala – all work stopped. Landlords attacked and set on fire the homes of workers, workers responded by setting on fire landlord houses. A prolonged strike had its impact. Ayyankali sought the help of the fishing community which allowed Pulaya men to accompany them on fishing boats and sharing the catch so that workers on strike and their households did not starve. The historical one year old strike forced the upper caste landlords to call for a negotiated settlement which included Pulaya children’s right to study in schools as well as agricultural workers demands such as wage hike.

Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham(SJPS) – uniting all sections

It was in this context that Ayyankali set up in 1907 the Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham (SJPS) with his co-workers Thomas and Harris Vadhyar, an organization for all sections of Dalits. Among its key resolutions were: six day working day (Sunday rest as demanded by workers), weekly meetings to discuss common problems every Sunday, membership fees of half Chakram (one of the denominations of the old currency of Travancore state) for men and one-fourth Chakram for women, thereby facilitating women’s entry into public, political space. He also started a magazine – “Sadhujana Paripalani” – for educating adults. The struggle for schooling persisted as in the case of Pulaya children admitted (1914) to Pullatu school in Thiruvalla, with upper caste boycotting the school and setting it on fire. However, Ayyankali intervened and forced them to accept the students.

Against symbols of caste slavery of women

The raising of other social rights followed, with Ayyankali called on women in south Travancore to throw away the stone bead necklaces – Kallumala, a symbol of caste slavery – and to wear clothing including upper cloth. This led to the most violent opposition from upper caste landlords who also started whipping workers – men and women who wore clothes and women threw away their bead necklaces and also resisted sexual exploitation by upper caste men/landlords. These assertions by women led to many attacks on them. The newspaper “Mitavadi”, Feb/April,1916, reported:

“…A man asked a Pulaya woman as to where her stone necklaces were. ‘I cut them off at the Sabha’, she answered. He took out a knife and said, ‘Right. Then I am cutting off your ear too’. We are saddened by this news. Though this happened in a state ruled by the local Raja; it is surprising that it happened when we were part of the British Empire…”

Also:

“We had reported earlier about a Pulaya woman’s ear being cut off near Kollam for not wearing stone ornaments. This has been repeated from other places also.”

This movement also spread, and in Central Travancore Pulaya youth organized and also took up weapons to defend themselves. The movement spread to many areas, including Cochin. A leader, Gopaldasan, was killed by the upper castes, leading to an explosive situation where, after a memorial meeting on October 24, 1915, men and women, some carrying sickles, attacked the upper castes and set their homes on fire. Ayyankali intervened. He prepared a report on the causes and progress of the struggle and submitted the same to the government.

All Community Meeting For Peace and Justice

A woman circus owner allowed her tent to be used for a meeting (Decmber 19, 1915) addressed by Ayyankali and chaired by Changanassery Parameshwaran Pillai. It was attended by over 4,000 persons of 11 castes and religions, according newspaper reports and Vellikkara Chodi, TV Thevan, Gopaldasan, etc. According to a newspaper report, among those present at the meeting held in Kollam on Sunday the 19 of December 19, 1915 were “Peshkar Rajarama Rao Esq, 1st Class Magistrate Govindappilla, two circle inspectors and a large number of constables. Prominent persons from various faiths, local leaders, advocates, traders, officials etc. came punctually and took their places. The leaders Ayyankali, Chodi etc. sat in front of the Sabha. Pulaya women and children had come dressed neatly dressed for the occasion. They listened to the proceedings in rapt attention.”

Ayyankali addressed the meeting saying:

“In southern part of our state our women have given up the custom of wearing stone ornaments to and have taken to ‘rowka’ (blouse) and other attractive clothes. It is against this change that the riots were engineered by the upper castes. I fervently hope that the savarna will cooperate in our programme to cut the stone jewellery in the presence of all community members gathered here for this Maha Sabha.”

He appealed again:

“As desired by Mr Ayyankali, members of all communities represented here are more than willing to let our sisters cut the strings holding together their stone jewellery.”

When the festival of handclapping lasting a couple of minutes ended, Ayyankali called two young girls to the stage. He said, “All gathered at this Sabha have agreed to let you to cut the stone jewellery adorning your neck. Cut them yourself and throw it away.”

No sooner had he called them, the two girls pulled out sickles stuck into their waist bands at the back and cut the ornaments and threw them on the stage. Thousands of others who had gathered cut the symbols of slavery and made a five foot high pile of stone necklaces, according to a report by Mitawadi.

Land Rights

In his first speech as member of the Praja Sabha held in 1912 at VJT Hall, Ayyankali, said:

“To fulfil the promise made to us about granting patta of plots from public land, we had applied to Neyyattinkara, Vilavamkode, Thiruvananthapuram, Nedumangadu taluk authorities. But nothing happened. The people of these taluks obstructed the process with the active connivance of some lower level workers of the revenue department. And whatever land the Pulayas found out to be public land was allotted to wealthy upper caste families. Not only that, the Pulayas were chased out of their humble homes and ended up without even what they possessed earlier. Except for asking the father like figure of govt for sympathy, we have no other way. Therefore, I pray for allotment of public land, and, as a test case some of the fallow land lying useless for our convenience and welfare.

“Many of our families have been evicted by rich land owners from our homes set up with oral assurance on their land. The forest officials are forcing my people to vacate their homes in the forests in collusion with landlords of the area. At the same time these very officials are helping the landlords to occupy these lands. Such illegalities have been done mainly in Valiyakavu in Chengannoor, Alapramuri in Changanassery taluk and Perumbaathumuri in Thiruvalla taluk. I pray for amelioration of such problems.”

Issues of educational concessions and employment in government departments were also taken up.

Identity and History

The two other radical reformers which formed organizations included Poikayil Yohana, who formed the Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha (PRDS) in 1909, and Pambadi John, who found the Cheramar Mahajana Sabha (TCMS) in 1921. Both engaged with religion to attack caste and caste slavery. For Poikayil Yohana, slave narratives and link with history of slavery informed the constitution of new selfhood and identity of all oppressed castes.

The Challenge

That the ‘commemoration’ of the early forms of radicalization – as exemplified by organizations such as Pulaya Mahjana Sabha and Ayyankali’s Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangam (SJPS) – have been turned into ‘events’, with diverse political claimants to its legacy, from the extreme left, Ayyankali Pada to Congress-I, and now Hindutva forces and its leader such as Narendra Modi. It suggests a serious challenge – the need to look into contemporary Dalit political socialites and their diverse trajectories. These seemingly smaller and complex trajectories need to be recognized as they are bound to intersect in varied ways with the larger and more visible political trends and scenario.

Dalit Movement in India After Death of Ambedkar!

mmediately after Ambedkar’s death, certain important developments took place in the Dalit movement. One was the formation of the Republican Party of India and the other was the formation of the Dalit Panther Movement. Many more Dalit associations/political parties/movements originated.More recently, Dalit Sathya Movement, the Dalit Ranghbhoomi, the All India Backward SC, OBC and Minority Communities Employees Federation, and the Bahujan Samaj Party came up. However, the Republican Party of India, The Dalit Panther’s Party, and the Bahujan Samaj Party have been more successful than the rest.

Republican Party of India:

The Republican Party of India replaced the All India Scheduled Castes Federation in 1957. Its founder was N. Sivaraj, who remained its President till 1964. The period during 1957-1959 is considered the Golden Age for the Republican Party.During this period all- its leaders focused their efforts on acceptance of the genuine demands of the Scheduled Castes, and when not successful they often protested. Its leaders such as B.K. Gaikwad, B.C. Kamble, Dighe, G.K. Mane, Hariharrao Sonule, Datta Katti, etc., were elected to the Parliament in 1957 where they raised such issues.The Republican Party of India worked in many areas such as: 1. To voice their concern against the atrocities committed to Dalits and to make them conscious.2. Revitalization of the Samata Sainik, founded by Dr Ambedkar in 1928, to maintain discipline in the party.3. All India/Women’s Conference was organized in 1957 at Nagpur.4. It contributed enormously to the Dalit Sahitya Sangh, the first conference was held in 1958 under the Chairmanship of B.C. Kamble.5. All India Republic Students Federation was established by the Republican Party of India.6. The Republican Party of India also spread the message of Lord Buddha.In 1954 and 1964, two satyagrahas were held with the demand of the distribution of land to the landless under the leadership of Dadasaheb Gaikwad. In 1964, yet another massive Satyagraha was launched by the party to force the government to distribute wasteland to the poor.In this regard, the party leader, including Gaikwad, Khobragade, and Maura presented a charter of demands to the then Prime Minister which included displaying the portrait of Ambedkar in the Central Hall of Parliament, giving the land to the tiller, distribution of wasteland to the poor and the landless, adequate distribution of grain, and control over rising prices, improvement of the situation of slum dwellers and Dalits, full implementation of the minimum wages of Act 1948, extension of the SC and ST privileges to those who have converted to Buddhism, to stop harassment of Dalits, full justice under the Untouchability Offence Act, and reservation for the Scheduled Castes and Tribes in services be completed by 1970.In 1967, the Republican Party of India formed an alliance with the Congress which led to erosion in its base. The alliance led to the split in the party with Khobragade and Gaikwad leading the two factions. In 1974, they patched up their differences and Khobragade was unanimously elected as its president. This again split the party into two groups: The Khobragade group and the R.S. Gavai group. In 1975, Gavai was elected as the president of the party. This led to the division of the party into three factions led by Gavai, Khobragade, and Kamble, respectively.The whole history of splits, reunions and renewed splits in RPI has no ideological basis, but they are due to clash of personalities and personal political ambitions. In fact, the Party failed to recognize the real cause of the problem of the Dalits and the leaders made choices as per their political convenience.The Dalit politicians were as much concerned about privileges and power as any other community leaders. They used their party banner to promote self-interests. This and the general discrimination against Scheduled Caste members led to the birth of the Dalit Panthers Movement in Maharashtra.

Dalit Panther Movement:

The Dalit Panther Movement was formed in 1972, when the Dalit youths came forward and took up the task of bringing all the Dalits on to one single platform and mobilizes them for the struggle for their civil rights and justice. It demonstrated that the lower castes were not willing to accept indignities and their worst conditions without protest.To Panthers, Dalit meant members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes, Neo-Buddhists, the working class, the landless and poor farmer, women, and all those who are being exploited politically, weaker economically, and neglected in the name of religion. The most crucial factor for the rise of the Dalit Panther Movement was the repression and terror under which the oppressed Scheduled Castes continued to live in the rural areas.The action plan for the Dalit Panthers was incorporated into the manifesto which consisted of 18 demands pertaining to the emancipation of Dalits. The manifesto reflected the enthusiasm of the Dalits to mobilize the poor masses in order to fight against the partisan and exploitative social system in the country.The Dalit Panther Movement spread to cities such as Bombay, Poona, Nasik, and Aurangabad where a large number of Dalit population is concentrated. Since its inception, the Panther Party was solely based on the ideology of Dr Ambedkar and was quite radical in nature. However, later in other states at least a faction of the Panthers was found inclined to the leftist, especially to the Marxist ideology. Namdev Dhasal and a few others firmly believed in the Marxist ideology.For him, the Dalit struggle is for a part of the larger design for the worlds oppressed. In this manner, they tried to create a class consciousness among the Dalits. They purposefully opted for confrontation and total revolution. However, they continued to draw inspiration from Dr Ambedkar also and a part of their ideology is drawn from Marxism as well.The other prominent figure of the movement. Raj Dhale, was finding some basic differences with the manifesto drafted by Dhasal. He accused Dhasal of receiving, Communist support. He also criticized the Communists of the country for having failed to bring any fundamental changes in the life of the downtrodden. Raj Dhale expelled Dhasal and some of his supporters for alleged disloyalty to the Panthers, majority of the followers remained with Raj Dhale.After the split in the organization in 1974, some Panthers united and continued the Dalit Panther Movement under the leadership of Prof Arun Kamble, Ramdas Athawale, and Gangadhar Gade. They took the initiative over the problems of reservation and other concessions granted to the Dalits in various parts of the country. In more recent years they revived the party by opening more branches in the northern part of the country.However, the movement is still confined to urban centers with majority of the Dalits concentrated in rural areas remaining untouched. Of late, the party has extended its focus outside Maharashtra and is trying to build up an all India Dalit Panthers Organization by opening a number of branches in various states.Some of the achievements of the Dalit Panthers are as follows: 1. Dalit Panther Party provided courage to fight against the ghastly incidents perpetrated on the Dalits.2. They shattered the myth that the untouchables are mute and passive.3. They raised their voice against the unjust caste system.4. They acted as a bulwark against the power politics and Republican Party leaders.5. They started a debate on Dr Ambedkar s ideology.6. They compelled the government to fill the backlog.7. They contributed immensely towards Dalit literature.8. They were able to create a counter culture and separate identity.9. They made popular the term “Dalit”, in preference to terms such as “Harijans” and “Untouchables”.10. They captured the imagination of the younger generation, projected a militant image through their tactics of confrontation.

Bahujan Samaj Party:

Bahujan Samaj Party was founded by Kanshi Ram in 1984. In 1984, it was formed to chiefly represent the Dalits, and claims to be inspired by the philosophy of Dr Ambedkar. With the demise of Kanshi Ram in 2006, Mayawati is now the undisputed leader of the party. Mayawati swept to power in 2007 Assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh for the fourth time. She served as the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister thrice earlier.The party has its main base in Uttar Pradesh. Since its inception, the growth of the party coincided with the growth of Kanshi Ram as the tallest leader of Dalits in India. He gained all-India significance along with Mayawati and started fighting for the rights of the Dalits.Both Kanshi Ram and Mayawati traveled across the states of Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Maharashtra, Bihar, and elsewhere. Through their speeches, Kanshi Ram and Mayawati appraised the Dalits of their socioeconomic, political, cultural, and educational rights and the ways and means through which, they could achieve their goals.They even posted some BSP workers in some areas in Delhi the State Capital, to spread the message of the Party and to help the Dalits fighting for their rights. Through Kanshi Rams efforts, Bahujan Samaj Party emerged as the savior and protector of Dalit rights.Kanshi Ram organized numerous meetings of Mahars in Maharashtra and fully appraised them of their socioeconomic status. He always emphasized the role of education for betterment. He argued for imparting technical and medical education to the young boys and girls of Dalits.He was keen that a substantial majority of them should become engineers and doctors showed a sense of optimism by his assertion that with the kind of opportunities available, anybody can become successful in life. Kanshi Ram had an ideology which is laced with politics, religion, culture, and education meant for the people of his community and for this he argues that once their base is strengthened, their progress would be spontaneous and a continuous phenomenon.He organized the youth wing of the Bahujan Samaj Party and opined that if the cadre was strong, the party would remain strong. Their responsibility included advising the Dalits about injustice done to them by the higher-caste Hindus for generations and under these conditions they were left with no option but to fight back.He stressed education for women. He was against the dowry evil. He warned all the people including Dalits not to take dowry. He was an advocate of prohibition. He highlighted the plight of the weaker sections, particularly the Dalits who had destroyed themselves under the influence of alcohol.He spoke against the migration from rural to urban areas. He described in detail the consequences of such a process. People who migrated found it difficult to find jobs. Even if they found one, they would find it extremely difficult to cope with the pressures associated with the job.

Very often, they would be forced to do menial works. He had a plan in view to devise ways and means which would greatly facilitate the execution of welfare policy which the Bahujan Samaj Party would like to implement.

Founding of the Scheduled Castes Federation

The All-India Scheduled Castes Federation was founded by Dr. Ambedkar in a national convention of the scheduled castes held at Nagpur and led by Rao Bahadur N.Shivraj, a renowned Dalit leader from Madras. An executive body of All India SCF was elected in the convention. Rao Bahadur N. Shivraj was elected as President and P.N.Rajbhoj from Bombay was elected as general secretary. The convention passed the following resolutions; 1) Cripps proposals to secure full Indian cooperation with the British goverment during World War II were condemned as they failed to consider the interests of the dalits. 2) The separate identity of the dalits be recognised. 3) Special provision should be made in the budgets of respective provinces for the higher education of the untouchables. 4) The untouchables should get adequate representation in the central and provincial ministries. 5) Certain seats should be reserved in the government services. 6) The untouchables should get representation in the legislatures and local self-governments in proportion to their population. 7) Their representatives should be elected by separate electorate. 8) There should be provision in the constitution for the separate settlements of the Scheduled castes. 9) They should be given arable uncultivated land for their livelihood. The role played by SCF in politico-legal activities is of great importance: it could enlist the participation of the Scheduled castes in politics, it was spread over almost all parts of the country, and it tried to aggregate the interests of the SC’s and to protect them. In Oct. 1943, the central assembly passed a resolution moved by Pyrelal Kureel Talib, SCF member, for the removal of restrictions on the untouchables in the military forces against holding post of officers. However, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar himself desired to wind up the SCF and establish a new party, the Republican party of India (RPI) which could be able to associate with all the depressed class people and work as a strong opposition party to the ruling Congress and strive for the success of democracy.

Bahishkrit Hitakrini Sabha Founded

JULY 20, 1924: Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha was established by Dr. B.R.Ambedkar in Damodar Hall of Mumbai, as the central organization for bringing about a new socio-political awareness among Dalit by removing the difficulties facing Dalits, and placing Dalit grievances before the Indian government. The founding principles of the Sabha were "Educate, Agitate and Organize”.

Cheramar Maha JanSabha Founded

The Cheramar Maha JanSabha was founded in Kerala by Pampady John Joseph. He was of the view that the caste name ‘Pulaya’ was disgraceful as it denoted pollution, therefore, he named it Cheramar which means ‘son of the soil’ of Kerala. The Cheramar Maha JanSabha attracted the converts and non-converts towards it. The Jansabha was founded to protest against the traditional attitude and customs of the caste Hindus and caste Hindu converts. In Cheramar Mahajan Sabha, caste Christians as well as untouchable Hindus were allowed to be the members. It gave a new awakening to the untouchables in Kerala.

The Adi Movements