Kerala’s first Dalit priest takes charge

PTI

Pathnamthitta (Ker),Updated: October 09, 2017

Yedu Krishnan is among six Dalits out of the 36 non-Brahmins recommended for appointment as priests by the Kerala Devaswom Recruitment Board.

Yedu Krishnan scripted history on Monday by becoming the first Dalit priest in Kerala to assume duties at the sanctum sanctorum of the Manappuram Lord Shiva Temple at nearby Thiruvalla.

In a landmark step, 36 non-brahmins were recently recommended for appointment in various temples under the Travancore Devaswom Board, which manages at least 1,248 shrines in the State, including the famous Lord Ayyappa temple at Sabarimala.

Son of P.K. Ravi and Leela, Mr. Krishnan (22) had undergone 10 years training in Tantra shastra. He is among six Dalits out of the 36 non-Brahmins recommended for appointment as priests by the Kerala Devaswom Recruitment Board.

The young priest took blessings of his guru K.K. Aniruddhan Thantri and entered the shrine with present chief priest Gopakumar Namboodiri, chanting mantras, temple officials said.

Hailing from Koratty in Thrissur district, Mr. Krishnan is a final year postgraduate student in Sanskrit. He had begun performing pooja at the age of 15 at a local temple near his house.

Mr. Krishan’s presence inside the sanctum sanctorum of the shrine comes at a time when Kerala is set to observe the 81st anniversary of the historic Temple Entry proclamation on November 12.

The proclamation was a royal decree, which opened the temples in the erstwhile state of Travancore to the so-called lower caste Hindus in 1936.

The Dalit priest who made history

'When I applied for the job of santhi, I applied as a person who was eligible.'

'When I joined the temple at the age of 21, it was because I got the 4th rank in the list.'

'Now, everybody is talking only about my caste. I am above all that; it doesn't matter to me and to the people with whom I am associated with.'

On October 10, 2017, when 21-year-old Yadhu Krishna, a Dalit santhi entered the sanctum sanctorum of the Manappuram Mahadeva temple near Tiruvalla in south Kerala as the melsanthi (main priest), he was creating history. Devaswom Minister Kadakampally Surendran termed the appointment of 36 non-Brahmins, including six Dalits, as pujaris in temples under the Travancore Devaswom Board as a 'a silent revolution and a model for others to follow'.

The Travancore Devaswom Board manages 1,248 temples, including the Lord Ayyappa temple at Sabarimala.

Yadhu Krishna, who is currently studying for a post graduate degree in Sanskrit, spoke to Rediff.com's Shobha Warrier about growing up as the son of daily wage-earning parents, creating history as the first Dalit santhi and his desire to get a PhD in Sanskrit.

My parents (Ravi and Leela) are daily wage workers and life was never easy when we were children. They had to really struggle to bring my brother and me up, but they saw to it that our lives were more or less comfortable.

We got electricity in our house only when my brother was in the 10th standard, but both of us never looked at lack of electricity as a drawback.

We had no desires, and never demanded anything from our parents; we were content with whatever we had.

We never felt envious of other kids who had TV and other material things at home. Material possessions never fascinated me, and I don't remember pestering my parents for anything.

My mother says that even as a 4 year old, I was very spiritual and respectful towards everyone. I became a vegetarian when I was six years old. If you ask me why I turned vegetarian, I don't know. I never enjoyed eating non-vegetarian food.

What changed my life completely was the Lord Ayyappa temple very close to my home. Somehow, I liked spending time at the temple, perhaps that was why I became spiritually inclined. Or, maybe because I am spiritually inclined, I preferred to spend time at the temple.

I am what I am today only because I grew up so close to the temple.

I was happiest when I was at the temple doing some chores.

Five boys -- including my brother and me -- helped the santhi at the temple by collecting flowers, making garlands, cleaning the temple, washing and keeping the puja vessels ready and making nivedyam (the prasad that is fed to the diety).

We used to collect firewood from the nearby areas for cooking. I was the youngest among the five.

When I was very small, the temple didn't have a proper deity; just a photo. The santhi did puja there, that too only once a month. I was around 11 when the elders in the village thought of calling a thantri (main priest) to install a deity at the temple, but nobody from the nearby areas was interested as the temple stood in a very small space.

Finally, K K Aniruddhan Thantri from Paravur agreed to come. When he was told that the temple didn't have much space, he said not to worry, soon it will expand.

When he came to the temple, he was impressed with us kids running around and doing so many things for the temple, that too with such devotion.

He asked us to come and learn at the Sri Gurudeva Vaidika Thantra Vidyapeethom in north Paravoor. It is because of him that my life changed completely.

Maybe because I spent a lot of time at the temple involving myself with the temple activities, I had this strong desire to be a santhi, to learn more about the scriptures, rituals and mantras. So, his invitation came as a boon to me.

As we were going to regular school, all five of us started going to the Vidyapeethom during weekends. Everything -- from food to fees to the stay -- was free for all of us. Our guru Aniruddhan Thantri had many students as his shishyas at the Vidyapeethom. I was never made to feel that I belonged to a particular community.

There was no talk of caste or creed, and all of us were treated equal.

Only when we reached a certain level of education were we allowed to do puja inside the temple. Fortunately, I attained deeksha when I was 12 years old.

At 15, I was allowed inside the temple. The first time I got the chance to do puja at the sanctum sanctorum at our Vidyapeethom, I was so tense and nervous that it took some time for me to realise what I was doing.

After I completed my schooling, I was advised to study Sanskrit, so I continued my studies at the Vidyapeethom and also at the college.

This year, I completed 10 years of Thantra tharpanam studies. When the Devaswom Board called for applications for the posts of santhi, my guru advised me and some others to apply. Though I am yet to complete my post graduation in Sanskrit, I wrote the test and attended the interview. If I came 4th in the rank list, it was only because of the teachers who teach us at the Vidyapeethom; they are all so knowledgeable and wise.

One of my gurus is doing his PhD on Vedic studies. At 21, I think I was the youngest among those who were selected this year.

After I joined the Mahadeva temple in Tiruvalla as a santhi, I have not been able to go to college. I want to finish my post graduate studies and then do a PhD in Sanskrit if possible.

Till the newspapers started describing me as a Dalit santhi who made history, I had not even thought about the caste I belong to. Those at the Vidyapeetham also became aware of this only then as my caste was never an issue there.

Describing me as a Dalit santhi came as a big surprise to me. I studied at a Vidyapeethom where nobody asked me about my caste. I studied at a place where we sat with our guru and had our food on Onam and Vishu.

When I applied for the job of santhi, I applied as a person who was eligible.

When I joined the temple as a melsanthi at the age of 21, it was because I got the 4th rank in the list.

Now, everybody is talking only about my caste. I am above all that; it doesn't matter to me and to the people with whom I am associated with.

I am in fact, amused.

To the bhaktas who come to the temple, I am just a santhi who does pujas and gives them prasadam. I never feel discriminated against and all the people who come to the temple respect me.

Everybody -- most of them are from the higher castes -- look at me as the santhi who could go inside the sanctum sanctorum to offer prayers.

Whoever does that is revered and respected irrespective of the person's age and caste. And that is how it should be.

I was taught by my gurus that we should not look at this as a job or a profession; this is devotion, a divine opportunity to serve God. Whatever that has happened in my life is niyogam, fate, destiny.

If there was no temple near my house, if my guru Aniruddhan Thantri had not come there and taken us to the Vidyapeethom, I would not have been here at all.

I would not have had the good fortune to be the shishya of such a great guru. So, everything in life happens with a purpose, and I believe in it.

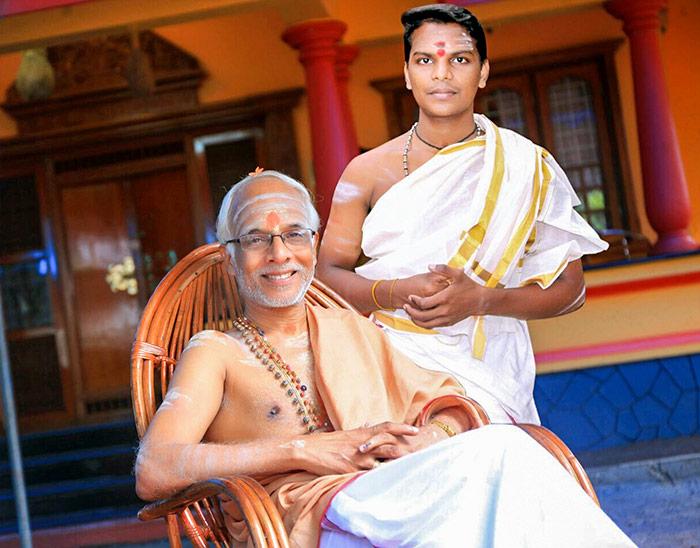

IMAGE: Yadhu Krishna, right, with his guru, K K Aniruddhan Thantri. Photograph: Kind courtesy Yadhu Krishna

Kerala Dalit priests: ‘Any Hindu can be a Brahmin’

Shaju Philip meets the five who made the cut and finds a new generation of Dalit priests, armed with degrees from some prominent Vedic colleges, and at ease with rituals, having learnt the ropes in private temples across the state

Written by Shaju Philip | Updated: June 26, 2018

Over nine decades ago, Dalits and backward castes weren’t even allowed in the vicinity of temples. (Source: Suresh Mamood)Kerala has for the first time allowed Dalit priests to take charge of government-owned temples, taking a giant stride in its sometimes stutter-filled path to social inclusion. Shaju Philip meets the five who made the cut and finds a new generation of Dalit priests, armed with degrees from prominent Vedic colleges, and at ease with rituals, having learnt the ropes in private temples across the state

Over nine decades ago, Dalits and backward castes weren’t even allowed in the vicinity of temples. (Source: Suresh Mamood)Kerala has for the first time allowed Dalit priests to take charge of government-owned temples, taking a giant stride in its sometimes stutter-filled path to social inclusion. Shaju Philip meets the five who made the cut and finds a new generation of Dalit priests, armed with degrees from prominent Vedic colleges, and at ease with rituals, having learnt the ropes in private temples across the stateOver nine decades ago, Dalits and backward castes weren’t even allowed in the vicinity of temples. It took the Vaikom Satyagraha of 1924 to ensure that temple roads in the then Travancore state were opened for all castes. It would take another 12 years and the royal decree of 1936 for Dalits and OBCs to be allowed entry into temples.

On October 9, this year, the Travancore Devaswom (Temple) Board (TDB) broke another major barrier towards social inclusion in the state, appointing five Dalits as priests to temples under its control. The entry into the sanctum sanctorum was facilitated by the TDB’s decision to select priests in line with the recruitment process followed in government posts, including adhering to reservation norms.

The TDB conducted an examination in 2016, held interviews early this year, and appointed 62 priests, of whom five are Dalits. While the current process faced little resistance, similar reform efforts in 1970, when around 10 members of the OBC community were appointed as priests, and in 1993, when OBC priests were finally allowed into temples, were vehemently opposed.

In 1970, following strong opposition from the Brahmin community, the TDB changed the 10 priests’ designations to clerks and shifted them out of the temples. And in 1993, it took Supreme Court intervention to finally pave the way for an OBC priest.

Unlike their predecessors, the new-age Dalit priests have worked at private temples. But being part of the TDB is an altogether different matter. The most prominent of the four autonomous temple boards in Kerala controlled by the state government, the TDB manages 1,252 temples in South and Central Kerala, has nearly 2,500 priests on its payroll, and handles an annual revenue of Rs 390 crore. Its portfolio includes 70 major temples, including the famous Ayyappa Temple at Sabarimala.

Yadukrishna at the Shiva temple in Valanjavattam, where he took over as chief priest on October 9 P R Yadukrishna, 21

Yadukrishna at the Shiva temple in Valanjavattam, where he took over as chief priest on October 9 P R Yadukrishna, 21Priest, Shiva Temple at Valanjavattom, Pathanamthitta Dist

With a sacred thread across his shoulder, ash and sandalwood paste smeared on his forehead and arms, P R Yadukrishna, clad in a crisp cream dhoti, looks every bit the archetypal temple priest. Only the 21-year-old has earned his thread, with his appointment as a priest, at the Shiva Temple at Valanjavattam in Central Kerala’s Pathanamthitta District, the first instance of a melsanthi (priest) being recruited on the basis of a rank list.

Yadukrishna, a member of the Scheduled Caste Pulaya community, traditionally toddy tappers, had finished fourth among 946 candidates, who had appeared in the maiden examination and interview conducted by the Travancore Devaswom Board (TDB). His entry into the sanctum sanctorum, however, is of much bigger significance — it marks another watershed milestone on the road to temple equality in Kerala, through reform processes that have lasted the last 100 years.

It is also, says the son of a farm worker from Chalakkudy in Thrissur district, the culmination of a long journey, which began with him hanging around the temple near his home. “I used to help the temple in my village by fetching flowers and washing utensils. My parents wanted me to become a temple priest. I even abandoned non-vegetarian food at the age of eight to become a priest,’’ says Yadukrishna, who is now pursuing a post-graduate course in Sanskrit.

Yadukrishna says he left formal schooling to focus on his dream of becoming a shanthikkaran (temple priest). “I have been helping to perform pujas from the age of 15. No one had asked me about my caste. Many of my friends who wanted to become priests abandoned the profession midway. But I stuck to it, hopeful of getting an opportunity. Now it has become a reality,’’ he says.

If protests and resistance had marked the appointment of the first priest from the backward classes in 1993, sentiments among the upper caste communities, it seems, have mellowed. On October 9 when Yadukrishna landed up with his appointment order, the faithful and local advisors of the Pathanamthitta temple, majority of them upper castes, ensured that the Dalit priest was taken to the temple in a procession. He also shares a home with Prakash Bhat, a senior Brahmin priest with another temple in Pathanamthitta.

Yadukrishna’s mentor, Anirudhan Tantri (senior priest), who established the Sree Gurudeva Vaidika Tantra Vidya Peedham at Paravur in Ernakulam district in 1987, remembers him as a “studious” boy keen on learning. “He came to me at the age of six as a helper who brings flowers for the puja at the Naalukettu Sree Dharma Sastha Temple at Chalakkudy,” says Tantri. Yadukrishna had enrolled for a tantric course at the Paravur institute, whose alumni work as priests across several temples in Kerala. The institute recruits teenaged, school-going youths, who are taught about various rituals and festivals in temples.

Pradeep Kumar has studied a tantric vidya course and is now studying an astrology course. (Suresh Mamood)

Pradeep Kumar has studied a tantric vidya course and is now studying an astrology course. (Suresh Mamood) Pradeep Kumar K M, 31 Priest, Dharma Sastha temple, Narayanamangalam in Ernakulam dist

Pradeep Kumar’s father, M K Karunakaran, too wanted to be a priest. “My father could not complete his studies. I have shouldered his dream,” says the 31-year-old, now appointed at the Dharma Sastha temple at Narayanamangalam in Ernakulam district.

Kumar, who has completed a vocational higher secondary course, says he began his journey into priesthood by offering daily rituals at the temple in his village of Perumbalam in Alappuzha district. He had initially stayed with a senior priest near Cherthala to learn the basics of rituals, but later joined a tantric vidya course at an institute run by the SNDP Yogam.

Now he is studying astrology. “Learning astrology is an added advantage for a temple priest,” says Kumar, whose wife Dhanya is an accountant with a private firm. Kumar says he was unaware of the exam being conducted by the Travancore Devaswom Board. “I applied for the post at the behest of a friend, who intimated to me about the board’s recruitment notification. In fact, I didn’t think about a job under the TDB as, before this, it has never appointed any Dalit priest,” Kumar says.

He adds that he didn’t need to prepare much for the examination, which was modelled on tests conducted by the State Public Service Commission. “We had to mark answers on OMR sheets. The questions pertained to puja practices and other temple matters,’’ Kumar says.

“I see this selection as a blessing from my parents and teachers,” says the priest, who has worked in private temples for 14 years. “So far, I haven’t faced any protests from devotees. Also in private temples, nobody normally looks into the background of priests,’’ he says.

Manoj says he cut his teeth as a junior priest, shuttling between privately-owned temples, for close to 22 years (Suresh Mamood)

Manoj says he cut his teeth as a junior priest, shuttling between privately-owned temples, for close to 22 years (Suresh Mamood) Manoj P C, 31 Priest, Siva Temple at Arakkappady near Perumbavur

About 115 km away from Valanjavattam, at Arakkappady near Perumbavur, Manoj P C has taken charge as the priest of the Siva Temple. The 31-year-old Dalit is the first member of his Vettuva community, traditionally coconut climbers, to be ordained as a priest of a TDB temple.

Manoj says that for close to 22 years, he cut his teeth as a priest in smaller and privately-owned shrines, in the shadow of upper caste priests, while moving from one temple to another, and subsisting on a meagre income.

In the private temples, mostly run by trusts, Dalit priests like Manoj work as assistants to the senior priests, who recommend them, and have little job security. They are also stop-gap arrangements, filling in when sitting priests go on leave. And their income would depend on the temple’s revenue and contributions while performing pujas.

“We would go for private pujas and people would hand in contributions. In the initial days of my career, my monthly income was less than Rs 1,000. In recent years, I had been getting between Rs 10,000 and Rs 12,000 a month from assisting the chief priests and working in small temples,’’ says the son of daily wagers. All that is set to change with his appointment. Under the Travancore board, salary is fixed in the Rs 10,620-16,460 scale for the newly-appointed priests, who have to undergo a one-year probation period.

The TDB priests are also entitled to pension after retirement, which would be one third of the last salary drawn. Manoj says he abandoned formal education at Class VII, to focus on studying temple rituals. “During my early school days, I used to assist the priest at the Subramania temple in my village of Nediyara in Ernakulam district,” he says.

He got a break, he says, when the main priest at the prominent Devi Temple in Mannanthala, which was consecrated by social reformer Narayana Guru, took him under his wing. “I was lucky to work as an assistant to the main priest Sabu Santhi. When I joined to learn rituals under Santhi, there were 10 of us. Later, most of them left the field. Even if we become masters in performing rituals, if we don’t get opportunities, we will never become priests,” he says.

After five years of studies, Manoj conducted his maiden puja at the Durga Devi Temple, Oruvathilkotta, near Thiruvananthapuram. Along the way, insists Manoj, he faced no discrimination. “I used to dine with Brahmin priests and we stayed together at the Durga Devi Temple in Thiruvananthapuram. Priests like Deva Narayanam Potti and Ambapapuzha Madusudhanan Namboothiri helped me a lot,” says Manoj.

Kerala Vettuva Maha Sabha president C V Subramanian says Manoj’s elevation would inspire youngsters from the community. “When society is heavily polarised over religion, a Vettuva priest in a temple catering to mainly upper caste Hindus has much significance. This would encourage more children from the Vettuva community to pursue a career in priesthood,” he says.

As the temple he serves is a small one, Jeevan is not expected to spend his entire day at the shrine (Suresh Mamood)

As the temple he serves is a small one, Jeevan is not expected to spend his entire day at the shrine (Suresh Mamood) Jeevan G, 26 Priest, Maha Vishnu Temple, Kaduthuruthy, Kottayam

In the four years he spent working in private temples, Jeevan G, 26, says he never once got an invitation from a Brahmin family to conduct a puja in their home. “Upper caste Nairs and members of the Ezhava community would invite us home for private pujas but never the Brahmin families,” says the youngest son of Gopalan, a farm worker and Thankamani, a homemaker.

Terming TDB’s decision as a revolutionary step, Jeevan says that the fact Dalit men like him have been able to benefit from it, is solely due to the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP), the social organisation that represents the numerically strong backward Ezhava community. The SNDP, he says, allowed Dalit men to learn about rituals in temples controlled by the Yogam. “Several Pulaya youth, including me, have got training in Ezhava temples. Without the gesture of that community, we would not have become priests,” he says.

Although Jeevan’s older brother Sandeep is also a temple priest, it was he who first moved into the profession. “My brother was a medical representative but later embraced this profession. In the last year-and-a-half, he has been working as a temporary priest in a private temple,” Jeevan says.

A bachelor, Jeevan’s spiritual grounding started early. “I began by assisting in temple matters during my school days. After Class 10, I joined as an assistant to senior priests at prominent temples,” says Jeevan, adding that his early years were marked by economic hardship, and to supplement his income, he worked as a daily labourer.

“The job at TDB is of great relief. After a one-year probation, a junior priest is entitled to a monthly salary of Rs 18,000,” says Jeevan, who unlike the other four Dalit priests, had earlier worked with the Travancore board. “I worked at a TDB temple on contractual basis for nine months,” he says.

Jeevan daily routine nowadays involves opening the Maha Vishnu Temple at 6 am and remaining there till 9.30 am. Since his home in Vaikkom is just 15 km from the temple, he returns home for lunch hours. Jeevan says he is then expected back at the temple at 5 pm. “This is a small temple, where a priest need not stay throughout the day. People are very cordial and many have personally come to meet me after hearing about a Dalit man being appointed to the temple,” says Jeevan.

Sumesh (second from left) with his family at their home in Karuvelil in Kollam district (Suresh Mamood)

Sumesh (second from left) with his family at their home in Karuvelil in Kollam district (Suresh Mamood) P S Sumesh, 35 Priest, Devi Temple, Nelluvila in Kollam district

P S Sumesh is well aware that the road ahead for the Dalit priests is a tough one. “We are the first Scheduled Caste priests in the Travancore Devaswom Board. We don’t have predecessors from the community to guide us on how to handle difficult situations. And we are yet to see what our presence will mean to the community of TDB priests,” says Sumesh, a member of the Pulaya community.

The Dalit priest is an anomaly in his family of government employees. His father K M Surendran had retired from the state municipal service as a clerk, his mother Ponnamma is an employee of the Animal Husbandry department, while his brother P S Sujesh is a police constable.

That, the priest at the Devi Temple, Nelluvila, in Kollam district says, is because his foray into the world of shrines was accidental. “When I was in school, a swami visited our village, Karuvelil in Kollam, and sought children who could regularly kindle the lamp at the small temple there. From the small crowd, the swami picked me. That was my way to priesthood,’’ recalls Sumesh.

A graduate in English, Sumesh has been working as a priest at various private temples for the past 10 years. “These days, most of the faithful do not bother about the caste of the priests. If we can deliver the result expected from a puja, we will be in demand. In such a situation, a priest has little to worry about caste,” insists Sumesh.

The priests says his job will finally provide him much needed stability. “The job at TDB is a permanent one and my parents had asked me to apply for it. Besides, one can rise up in the TDB and retire as a senior priest with all benefits,’’ he explains.

Sumesh also says his first salary would go to his guru, who he credits for having groomed him as a priest. “Becoming a temple priest is a long process. An aspirant cannot just become the disciple of a priest one fine day. The senior priest or tantri would closely observe an aspirant for months. I, for instance, was under the observation of my guru Sankaranarayan Potti for six months. Only if the guru is convinced about one’s intentions and impressed by one’s behaviour, would he accommodate one as a disciple,” says Sumesh.

Only Dalit women are allowed to touch the deities in this ancient Odisha temple

Janaki Dalai is one of four women priestesses who take care of the Panchubarahi temple. | Photo Credit: Biswaranjan Rout

more-in

The temple has now been relocated from its sea-ravaged location, and its priestesses as well

When Janaki married Sukadev Dalai and moved to Satabhaya village in Odisha’s Kendrapara district, she had no inkling of the traditions she was stepping into and the mantle she was carrying forward. But when her mother-in-law took her to the Panchubarahi village temple and taught her the rituals there, she joined a 300-year-old legacy of exclusively Dalit women priestesses, from the Sabar caste, who head this seaside temple.

While there is no historical evidence for the age of the temple, residents of the village claim the temple has not always had priestesses in charge. “Legend has it that a male Brahmin priest once saw the deities unclothed, and was cursed to become a stone. Thereafter, women were roped in to conduct daily rituals and no man could touch the idols. The tradition had been carried on since,” says Sibendra Bhanjdeo, scion of the erstwhile Rajkanika zamindari and chief trustee of the temple.

Four priestesses conduct the daily rituals on a rotational basis for 15 days each. “We are descendants of Jara Sabar, who accidentally shot an arrow and took Krishna’s life,” says Janaki. A repentant Jara Sabar is said to have become an ardent devotee, worshipping a piece of Krishna’s body. “For our community, performing puja for Krishna is not new,” says Janaki.

Second fiddle

The priestesses’ husbands take it for granted that they have to play second fiddle to their wives in matters concerning the temple. “It is an honour to be Janaki’s husband. Our family takes immense pride in her being a priestess and it elevates our social status,” says Sukadev.

“Our husbands can enter the temple, but cannot touch the deities. They collect fruits and flowers from devotees and hand them to us to offer to the goddesses,” says Sujata, another priestess.

In this temple, the priestesses aren’t expected to recite hymns in fluent Sanskrit, or be familiar with complex rituals , or wear specific temple attire. “We just seek the blessings of our deities for the devotees who come here,” says Janaki.

The former kings of this zamindari had chosen four families to look after the temple and its deities. At present, there are four such assigned families in Satabhaya village, and the priestess-hood is generally bestowed upon the eldest daughters-in-law of these families in hereditary succession. The priestesses aren’t paid for their vocation, and the days they aren’t in the temple are spent working at home.

Panchubarahi itself is no ordinary temple. At its earlier location on the edge of the sea, it was often battered by incessant rain, tropical cyclones and tidal waves. The extreme weather, however, didn’t seem to dampen the spirit of these intrepid priestesses, as the temple stood mute testimony to the advancing sea.

Then, in 1971, when Odisha was ravaged by a cyclone, more than 700 villagers were swept away into the Bay of Bengal. And the 16 hamlets of Satabhaya, spread over 3,440 acres, were reduced to a few hamlets.

Relocating divinity

Satabhaya has never been exactly easy to access. You had to walk down an 8 km long serpentine road after crossing the crocodile-infested Baunsagadi river on a country boat. During the monsoons, the village would become almost fully inaccessible, and villagers would be choked of even basic services.

Finally, last month, it was decided that human habitation could no longer continue here. The people of this isolated, sea-ravaged village were relocated to a new settlement in Bagapatia, some 10 km away.

Along with them, the temple and its deities too were shifted to a suitable spot in the new village. That was when, for the first time in centuries, men had to be allowed into the temple to lift the three heavy idols, weighing almost six quintals each, and move them to their new home. After the relocation, the priestesses took over again, shutting the men out.

The 571 families who have started living in the new village have started flocking to the temple again.

A few families still cling on to the old Satabhaya, claiming that they have not been properly rehabilitated and compensated yet. Meanwhile, Satabhaya village itself has been declared part of the Bhitarkanika wildlife sanctuary, at one with the sea and the birds.

satyasundar.b@thehindu.co.in

Phalahari Suryavanshi Das

From an outcast to a temple priest

Ashwaq Masoodi

The journey of Phalahari Suryavanshi Das, a Dalit priest at Patna's Mahavir temple, exemplifies a small but significant step to break the caste barrier in Bihar

Topics

Patna: Two priests stand before flower-draped Hanuman idols, accepting offerings from devotees; plucking a flower from among those adorning the deities and adding it to the prasad as a blessing, before returning it to the devotees waiting with folded hands and bowed heads. The air inside Patna’s Mahavir temple reverberates with chants of Hanuman Chalisa and the Ramayana’s Sundar Kand, punctuated by the intermittent ringing of the temple bell. Most devotees leave after the priests hand them the prasad and lightly touch their heads in blessing; a few touch the priests’ feet.

The ritual is perhaps typical of most temples in India. What is distinctive in this particular temple is the identity of the priests presiding over rituals in the sanctum sanctorum. On the right, dressed in a lemon kurta and white pyjama, with hair neatly parted on one side is Dwarka Das, 35, and a Brahmin. On the left, in a white dhoti and matching uparē (shawl worn over the shoulders), with long stringy locks of hair that resemble dreadlocks, is Phalahari Suryavanshi Das. He is 62 years old and a Dalit.

“A Dalit priest standing shoulder to shoulder with a Brahmin priest inside one of the largest temples, frequented by all castes, is symbolic in itself. It is a marker of the social change that’s slowly happening...at least here," says Acharya Kishore Kunal, a retired IPS officer and former chairman of the Bihar State Board of Religious Trusts.

Priesthood among Hindus has traditionally been an upper caste monopoly. At a time when Dalits in several parts of the country are fighting for the right even to enter temples, the presence of a Dalit priest in the sanctum sanctorum of a 300-year-old temple is remarkable.

A Dalit priest standing shoulder to shoulder with a Brahmin priest inside one of the largest temples, frequented by all castes, is symbolic in itself. It is a marker of the social change that’s slowly happening...at least here-

Acharya Kishore Kunal, retired IPS officer and former chairman of Bihar State Board of Religious Trusts

Spending some time in the temple shows this is not mere tokenism. “Even the first time when I came here, I knew who the priest was. Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras...all are the same in front of god and this temple just reinforces that. Every time I come here, I make sure I touch Phalahari baba’s feet at least once," says Vinay Aggarwal, a 50-year-old businessman who visits the temple every day on his way to work.

There is authority and fearlessness in Suryavanshi Das’s eyes, and confidence that shows that he has long been accepted by the people of Patna and is no longer the “other". In fact, he says, there have been instances when even “Brahmin intellectuals" have come for his darshan.

“I am a Mahatma. I never thought of myself as a Dalit. When you become a Mahatma, you abandon all such worldly identities. Saint Ramananda said, ‘Jaati panthi pucchai nahi koi, hari ko bhaje so hari ka hoi (Let no one ask of caste or sect; if anyone worships God, then he is God’s).’ Upper and lower castes are not the creation of God. It is our creation," says Suryavanshi Das, who only eats fruits, hence the name Phalahari.

There is authority and fearlessness in Suryavanshi Das’s eyes, and confidence that shows that he has long been accepted by the people of Patna and is no longer the ‘other’

Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar, who fought for the rights of the Dalits and other socially backward classes, vehemently criticized the Brahmin monopoly over priesthood in a speech titled Annihilation of Caste, which was written for the 1936 annual conference of Hindu reformist group Jat-Pat Todak Mandal, but never delivered as his invitation was withdrawn due to the speech’s content. “The profession of a Hindu priest is the only profession which is not subject to any code... The priestly class must be brought under control by some such legislation... It will democratise it (priesthood) by throwing it open to everyone. It will certainly help to kill Brahminism and will also help to kill caste, which is nothing but Brahminism incarnate," Ambedkar wrote in the speech.

Acharya Kishore Kunal, who as the caretaker of the temple, was instrumental in installing Das as a priest. Photo: Indranil Bhoumik/Mint

Acharya Kishore Kunal, who as the caretaker of the temple, was instrumental in installing Das as a priest. Photo: Indranil Bhoumik/MintIn Bihar, the beginning of this change started on 13 June 1993, when a three-member delegation escorted Suryavanshi Das as he stepped into the sanctum sanctorum of the Mahavir temple late that afternoon. The presence of the three priests—Ramchandra Paramahans, Mahant Avaidyanath of Baba Gorakhnath Dham and Mahant Avadh Kishore Das, indicated that Suryavanshi Das’s appointment had received the stamp of approval. But behind all this was Kunal, who as the caretaker of the temple took it upon himself to change the social order and break the caste barrier. It was he who institutionalized philanthropy through the temple and slowly built a reputation for himself and the temple.

A Hanuman temple appointing a Dalit priest would ordinarily have resulted in some kind of resistance from the locals in a state where caste still remains relevant. But it didn’t. “This change was endorsed by three important priests of the time. And by then, people knew me as a true devotee. People trusted me. Had I come forward as a progressive liberal talking about change, I doubt I would have been successful in bringing about this change," says Kunal.

The installation of Dalit priests in more than a dozen temples in Bihar does not mean caste has become irrelevant in the country or even the state, but it is definitely a small step towards breaking the barrier

India’s centuries-old caste hierarchy deemed those born in the so-called lower castes to be so unclean that they couldn’t even be touched. Untouchability was officially outlawed in 1950, but many continue to believe that touching some lower castes would make them impure. In this backdrop, Kunal’s dream of making caste irrelevant was not realistic.

Kunal personally visited Ayodhya’s Sant Ravidas temple, to request the head priest there to send a pujari for the Mahavir temple in Patna. Ravidas was a 15th century Bhakti saint who advocated “inclusive coexistence" in a casteless and classless society. Dalits revere him as a saint and have built several temples in his name.

Kunal says he thought he would be lynched at Ayodhya or Varanasi for suggesting such blasphemy, but surprisingly nothing happened.

Initially, those at the Ravidas temple thought perhaps Kunal had some political aspirations and was doing this to get the Dalit vote. For this reason, they did not immediately offer any of their priests. But within a few days, Suryavanshi Das was selected after he and several others were interviewed.

“It was an experiment that I was trying. I chose temples because I believe that in this country, you can become a Prime Minister being a Dalit, but it is nearly impossible to become a temple priest. Till now, I have installed Dalit priests in over a dozen temples here," says Kunal, who has written a three-volume book titled Dalit Devo Bhav, which demolishes “myths" around caste-discrimination in Hindu society and the place of Dalits in history.

There was some initial resistance. Some people warned Kunal about the possible repercussions of appointing a Dalit priest, but ultimately, it all went about smoothly.

“I never thought, nor had I ever heard about a Dalit priest in a temple where all castes would come till then, but I wasn’t scared. I was sure about my knowledge, and I knew I had the backing of so many respectable people. I was proud of myself. Even today, I am more revered than any other priest in this temple," says Suryavanshi Das.

His childhood memories centre around being forced to sit in the back rows of the classroom because how could a Dalit even sit with the upper castes? From there to seeing his name etched on marble plates outside temples he has inaugurated, life has changed dramatically for him.

The installation of Dalit priests in more than a dozen temples in Bihar does not mean caste has become irrelevant in the country or even the state, but it is definitely a small step towards breaking the barrier.

The world of work for Dalits has long meant joining a tiny pool of occupations—manual scavenging and leather tanning for instance. Discrimination is still rife in many occupations but there are Dalits who are pushing back against caste barriers by entering these forbidden territories. This three-part series will trace the history of work-based discrimination against Dalits by profiling three trailblazers.

The ruminations of Vimal Das, Dalit and Hindu priest

Rahul Chandran

Vimal Das, a member of the Ezhava caste in Kerala, on his life as a priest at a Hindu temple

Topics

Editor’s note: Vimal Das, 31, is one of six priests at a small temple to the sages or rishis that appear in Hindu mythology. Das was born an Ezhava, a caste considered untouchable and which until 1936 was not even allowed to enter most temples to pray. The Ezhavas are also a community that the Bharatiya Janata Party—traditionally a party of the upper castes—has chosen as the best way to enter Kerala, a state that is otherwise dominated by the left parties and the Congress.

Das speaks on his life as a priest at the Agasthyashram temple in Tripunithura, his aspirations and why he is trying for a job in a government run temple. The portions in italics are added context, such as the series of events that led to priests like Das.

I am from village Arookutty.

My family has around 17 priests, including my father’s and mother’s families. I was fascinated by the status these people have, the respect they are given by others, the prestige they have in the family. I wanted to be like them.

When there were functions at home, I got to speak to the priests. And that is how I came to feel that I should also do this. They had said that it would be useful only if you started learning (the mantras) at a young age.

Our mind can get split in many different ways. So, after my 10th standard I got into this. Plus One and Plus Two (the equivalent of Class XI and Class XII; the reference is to 10 plus one and 10 plus two) I did even as I began studying for this.

They told me that these things I could never study as a day scholar. I would have to go live in the quarters of temple workers and live (and learn) from them. If we are at home, we can eat whatever we want. You have to wake up in the right manner. After waking up, you have to sit on the bed, and before you plant your feet on the ground, you have to pray.

Then we can go, after washing our hands and feet, for our primary needs (i.e. going to the toilet, etc.). Once you learn the proper procedure for all these things, then it is by-heart.

Ezhavas yenna chattakoodinagathu nirthanda avashamilla (It is not just the Ezhavas). All Hindus, apart from Brahmins, could not (perform pujas at temples). The yogyada (eligibility) to enter a temple and pray for all Hindus was given by Sree Narayana guru. In the old days, if a non-Brahmin even heard Vedic chants, they would pour melted eeyam (lead) into his ears.

When Narayana guru expressed a desire to establish a temple (which meant performing the necessary tantric rites), the sa-varnas (those people who fell into one of the four varnas, as opposed to the avarnas, better known as Dalits or Harijans) said you are not even allowed to enter the temple or consecrate an idol. So, in 1888, Sri Narayana guru consecrated a temple at Arivikulam.

Das’s officiating as a priest was made possible by generations of protests for equality, culminating in what is called the Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936 issued by Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, the ruler of the princely state of Travancore.

It is said that Balarama Varma and his advisers were wary of the threat of mass conversion to Christianity, if regressive laws that applied only to lower-caste Hindus (such as restrictions on the right to walk on public roads near the temples) were not lifted.

In neighbouring Tamil Nadu, a largely symbolic government move to get more Dalit priests backfired when, at first, even Dalits did not want Dalit priests to officiate at their religious ceremonies. In 2015, the Supreme Court overturned the government attempt to appoint Dalit priests.

“The Dalits have historically been priests in Hindu temples that are linked to Vedic culture." But when these temples reach above a certain limit in revenues, the (state) government takes control over them. And if the government taking over a temple is a positive, the negative is that they end up replacing the original Dalit priests with Brahmin ones, said Stalin Rajangam, a professor at Madurai American college and a Dalit writer and scholar.

So, when my guru took up a temple in Varkala, they had need for two or three santhis and so I was taken along. I could help them and I could also learn. I was 19 then. And it is from there that I went to study (for my engineering degree).

There were two temples I had to work at. The main temple and a smaller temple that had only evening prayers. In between, I had a once-a-week class (on religious studies) that I had to make up.

(But) I couldn’t handle both (the religious studies at the temple in Varkala and the B.Tech. course). So I wound it up.

According to Sunny Kapikad, a prominent Malayali atheist and Dalit writer, the Dalits as a community did not even want to become priests in temples. Hinduism, he said, wanted the Dalits to be embraced within its fold.

Individual Dalits may have wanted to become priests, but as a community they did not express such a desire, according to Kapikad. The enveloping of the Dalits into the Hindu fold has itself taken on different forms in the two southernmost states of peninsular India. In Kerala, it has taken the form of Dalits occupying positions previously occupied by Brahmins, and adhering to Brahminical conventions such as ritual cleanliness, Vedic Hinduism and praying to Vedic gods.

I have an older brother and a younger brother. One is in Coimbatore, where he works as a designer for a company. One is an electrical and plumbing contractor. My family is supportive of what I do. I still don’t regret this job. I haven’t felt I shouldn’t have done it. I am completely satisfied with my life.

Here I get Rs12,000 a month. But, at the Devaswom, I would get Rs18,000 if I were to be hired as a part-timer.

The Devaswom boards are government bodies that administer some 3,000 temples in Kerala. There are four such boards in the state. Prayar Gopalakrishnan, the president of the Travancore Devaswon Board in Thiruvananthapuram, said the board had 75 vacancies. He did not hazard a guess on how many applicants there were, although Vimal Das said 25,000 probably gave the entrance exam, out of which 200 were called for an interview.

My father had an oil mill. About six years back, he had a mild heart attack. So after that, he isn’t going to work because he has three male children. He does a little farming, some work around the house. Mum is a housewife.

I have applied for a job as a priest at the Thiruvithamkoor Devaswom Board because our life will be settled. I can continue doing this work as long as I am healthy. But after my health is gone, life will become a question mark. If I work for the Devaswom board, then my pujas and other things will continue and if I am unable to perform the pujas (because of ill health), then I get pension. (Then) we will be able to take life forward somehow.

Can we marry? Definitely, we can. Even the statues we worship are considered the result of a man and woman’s union. That is the theory behind it. So, even in the rituals we do, there is this man-woman union. So, marriage is definitely not forbidden for us.

I would like to marry too. Not for any other reason but our tantric puja vidhanangalil, there are many pujas that you have to do with your wife. Even the wooden planks on which we sit when we do the pujas have a portion for our wives to sit on. Not that I (want to marry just so) I can do these things.

But some gods and goddesses, brahmacharyam (bachelorhood). Now, Hanuman Swamy (the Hindu monkey god who helped Hindu god Rama rescue Sita). When we do pujas for Hanuman Swamy, we are supposed to observe celibacy or bachelorhood. There is a kind of rule that you cannot think unnecessarily of women, or go near them or talk to them. It is an unwritten rule.

Now, in Sabarimala, there is (all this talk) that women cannot enter. (Das is referring to the ongoing controversy over whether women should be allowed to enter the hill shrine.) It isn’t as if all women aren’t allowed to enter. Only women who have started getting their menses cannot enter. It is not as if the fear is that (the deity) Lord Ayyappan’s bachelor celibacy would somehow be spoiled when women (of a certain age group) enter. But it may affect the men who come there to worship him. This is not just my personal viewpoint but that of many of us (priests).

Ayyappa Swamy of Sabarimala is not opposed to all women. If he were, they wouldn’t allow girls who haven’t started menstruating yet, or our mothers who have stopped menstruating would not be allowed.

At the time of the consecration of the idol, it was written down that Lord Ayyappan was a bachelor.

On caste

The Rig Veda says merely that the castes have been differentiated. it doesn’t say that (some) people should never be (allowed in the temple). It was the sa-varna medhavis (lords) who made these keezhvazhakoms (rules) just so it stays with them. You cannot be a Brahmin by janmam (birth). You can be a Namboodiri (a Brahmin caste) by birth. But you can only be a Brahmin by karmam (actions). If you want to become a Brahmin, you have to have done 10 karmams. Only then will he become a Brahmin. How can anybody have done these 10 things at birth?

The 10 karmams involve the ability to control indiryams, such as lust, as well as telling truth, maintaining the knowledge of the Vedas and belief in god.

These 10 things you have to know to be worthy of being called a Brahmin. That is what the Vedas say. By birth, you can become a Namboodiri. But to become a Brahmin, you must have all these skills.

It is not enough if you have these skills. You must have done certain acts too. You must study a lot of things. But you must teach these things to those that don’t know too. You must give alms to those that don’t have something. But you must also take alms when you don’t have. These are things a Brahmin must do.

On how important the government job is to him

One or two people have suggested to me "if you have Rs1 lakh or Rs2 lakh, we can get you inside". I don’t have the money for that. If I am to get (the job), let me get it from the things I have learnt.

If not, then no need. I will come back to this temple and do the pujas. I am satisfied. I only see one plus point in the Devaswom board job. Tomorrow, if for some health reason, I am unable to do pujas, I will get a (government) pension to continue my upa jeevanam (living).

Nidheesh M.K. contributed to this article.

Dalit women appointed as Hindu priests Pair believed to be first lower caste women admitted to priesthood

Ritu Sharma, Delhi

October 3, 2014

A century-old temple in the southern Indian state of Karnataka has appointed two lower caste Dalit women as Hindu priests.

Laxmi, 65, and Chandravathi, 46, both widows who belong to the dalit (former untouchables) community, were appointed priests of Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple in Mangalore, on Sept 29 2014.

"The two women have been appointed after training by the head priest of the temple. They have started conducting prayers in the temple," Hari Krishna Bantval, a member of the development committee of the temple, told ucanews.com.

While this was not the first time the temple had inducted women as priests, it was believed to be the first time dalit women were consecrated, temple officials said.

Members of the dalit community in the past were prohibited from sharing space with people of higher castes, particularly in temples. The community members are generally associated with doing menial jobs such as manual scavenging, cleaning streets and sewers and are considered impure. While laws have been put in place to protect their rights, dalits are still discriminated against in many segments of Indian society, particularly in rural areas.

The two women belong to the Billawa Community, traditionally suppressed by upper castes who regard them as untouchables.

Bantval said that the Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple does not believe in the caste system. "This is a step toward social transformation," he said.

People from all communities – Hindus, Muslims and Christians – come to pray at the temple, which was founded in 1912 by social reformer Narayana Guru, Bantval said.

India temple appoints two Dalit widows as priests

By Imran Qureshi BBC Hindi, Bangalore

1 October 2014

Image caption The two women (in orange robes) were appointed priests at a colourful ceremony

Two Dalit widows have been appointed as priests at a temple in south-west India, in a rare move for a country where caste prejudice is still rife.

The temple, in Karnataka state's coastal city Mangalore, was founded by social reformer Narayana Guru in 1912.

Widows have been allowed to perform rituals there before, but never Dalits.

Dalits, India's lowest caste, still face widespread discrimination, despite the country's prohibition of the practice in 1995.

Lakshmi, 65, and 46-year-old Chandravathi, were received at the entrance to the Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple by a former government minister, Janardhan Poojary, and other temple officials.

Mr Poojary said the women were selected "according to the teachings of social reformer Sri Narayana Guru", who considered everyone equally as children of God.

He told the BBC that his own childhood experience of caste discrimination, from within the Billava community, had strengthened his resolve to address a problem which persists despite various laws prohibiting it.

"I have seen the plight of the untouchables because I have myself suffered it. I am part of the toddy-tapping community of Billava who were barred from entering the temple. We were told we are not children of God," he said.

'Revolutionary step' Some local commentators in Karnataka have welcomed the move.

"What Poojary has done is outstanding. It is revolutionary. People of lower castes are not even allowed to enter the sanctum santorum," the writer K Marulasiddappa said.

The Dalit writer Indudhara Honnapura said he is confident it will happen "elsewhere [in India] too".

Reports say the two widow priests will now receive at least three years of further training by the chief priest at the temple, Lakshman "Shanti", but temple officials did not confirm this.

The temple was renovated in 1991 and inaugurated by the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi.

In 2012 his widow, Sonia, attended celebrations to mark the temple's centenary, when 5,000 widows were first allowed to enter the temple and perform "puja" or religious rites.

The practice of untouchability, in which members of India's higher castes will not touch anything that has come into physical contact with those at the bottom, still exists in the world's largest democracy despite being banned.

This story is from October 30, 2015

Dalit priests presiding over UP temple for past 200 years

Faiz Rahman Siddiqui | TNN | Updated: Oct 29, 2015

KANPUR: Amid reports of atrocities against dalits from some parts of the country, a nondescript temple on the banks of the Yamuna in Lakhna town in Etawah district stands out as a ray of hope with its unique 200-year-old tradition. Here, devotees — be they brahmin, thakur, vaishya or from any other caste — bow in front of dalit priests and perform puja and other rituals with their help.

“Since the past 200 years, only dalits have been priests at Kali Mata temple,” said priest Akhilesh Kumar and his brother Ashok Kumar. One of their ancestors, Chotey Lal, was the temple’s first priest.

Brahmins, thakurs and vaishyas in and around Etawah and from as far as neighbouring Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan visit the temple through the year.

“The priests of the temple are revered by all upper-caste people, who offer them garlands and offerings of fruits during rituals,” said Tribhuvan Singh, former block pramukh of the area. “The dalit priest, who sits at the ‘hawan kund’, prays and blesses people by offering ‘prasad’.”

Legend has it that in 1820, local ruler Jaswant Rao built the temple and appointed Chotey Lal as the first dalit priest to show respect towards lower-caste people. “King Jaswant Rao, who got the temple constructed, made it mandatory that the temple priest would only be a dalit,” said Dashrath Singh, a grocery shop owner in Lakhna.

Ram Sumer, a resident, told another tale associated with the custom. “Our ancestors used to tell us that during construction of the temple, King Jaswant Rao had got angry when he saw a group of upper-caste men beat up a dalit labourer, Chotey Lal, for touching the idol that was to be installed in the temple,” he said. “He issued a diktat that only Chotey Lal and his future generations would take care of the temple.”

Residents of Lakhna seek out dalit priests even for weddings, ‘mundan’ (tonsure ceremony) or other rituals. “During these disturbing times, one only needs to look to this 200-year-old place — where priests belonging to the dalit community are held in high esteem — for inspiration,” said Ram Das, another local of Lakhna.

Gorakhpur: Temple appoints Dalit as head priest, sets example

A temple in Uttar Pradesh’s Gorakhpur has smashed anti-Dalit image of Hindu temples by positioning Dalits at higher echelons of the institution. The Guru Gorakhnath temple has Kamal Nath, a Dalit, as its head priest. Pardeshi Ram, a Dalit, is the in-charge of Gaushala. The temple’s kitchen is also run by a Dalit. Not only the temple’s door is open for Dalits, devotees of all religions are welcomed here without any prejudice.

Ancient Bihar temples show the way with non-Brahmin priests

Much before the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that non-Brahmins can also be temple priests, nearly a dozen temples in Bihar has had non-Brahmins priests at its helm without any protests. Dec 21, 2015

Arun Kumar

Hindustan Times

Patna’s Mahavir Mandir has a Dalit priest at its helm. (PTI)

Much before the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that non-Brahmins can also be temple priests, nearly a dozen temples in Bihar has had non-Brahmins priests at its helm without any protests.

A living example is Patna’s over 300- year- old Mahavir Mandir, which has a Dalit priest, Suryavanshi Falahari Das, at its helm.

Das, who assumed the responsibility in 1993 in the presence of eminent religious leaders, is the oldest among the temple priests and commands tremendous respect.

There are several other temples and mutts, which have had a smooth transition in the last couple of decades. “It is a testimony to Bihar’s tolerant and all-inclusive fabric that it all happened quietly and with the support of the local community. There was no discrimination, as they were all as capable as any other priest. We also plan to start an institution for religious rituals in Hajipur, where anyone interested can get enrolled,” said Acharya Kishore Kunal, president of the Bihar state board of religious trust.

Kunal has written a 2,200page book ‘Dalit Devo Bhava’ on Dalit priests in three parts. The first two parts of which have been published by Publications Division, government of India, while the third part will be published soon.

“The book states that people from all castes and groups have the right to be appointed as priests or mahants. In fact, many important temples were established by Dalits,” he added.

Citing the example of a temple in Sitamadhi (Nawada), he said, people believe that Sita of Ramayana spent time there during her forest stay and also gave birth to Lav and Kush. “Here almost all caste groups have their temples and scheduled caste and backwards are a majority here,” he added.

In Dhaneshwar Nath Mahadeo temple in Simaria, he said, people of Kumhar (potter) community are made priests and pandas.

“The temple is quite similar to the Baidyanath Dham temple and also has a Shiv Ganga adjacent to it. It was by built by Raja Pratap Singh of Gidhaur,” he said.

Read at:

Any Hindu can be priest: SC

The Supreme Court today ruled that any Hindu person irrespective of caste or creed could be appointed temple priest, provided the governing Agama Shastras (the temple tenets) permit it.

By Our Legal Correspondent

Published 17.12.15

AddThis Sharing Buttons

New Delhi, Dec. 16: The Supreme Court today ruled that any Hindu person irrespective of caste or creed could be appointed temple priest, provided the governing Agama Shastras (the temple tenets) permit it.

In other words, if the tenets allow a Dalit, tribal or any other backward class individual as a priest, he/she cannot be disqualified on the ground that the job is the exclusive privilege of Brahmins.

In delivering the judgment, a bench of Justices Ranjan Gogoi and N.V. Ramana struck a delicate balance between Articles 25 (right to practise one's religious beliefs) and Article 26 (right to manage one's religious affairs) of the Constitution and Article 14 (equality before law), Article 15 (prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth), Article 16 (equality of opportunity in public appointments) and Article 17 (forbidding untouchability).

"....the exclusion of some and inclusion of a particular segment or denomination for appointment as archakas (priests) would not violate Article 14 (equality) so long as such inclusion/exclusion is not based on the criteria of caste, birth or any other constitutionally unacceptable parameter," Justice Gogoi, writing the judgment, said.

The ruling came as the court disposed of a batch of petitions by some upper caste persons and priests challenging a 2006 Tamil Nadu government order permitting any Hindu person to be appointed temple priests irrespective of caste and creed.#

A strong belief exists among upper caste priests, mainly Brahmins, that permitting other caste groups from entering the sanctum sanctorum or performing puja would defile the temple itself and is contrary to the shastras.

In this context, the court referred to Article 16(5) - related to equality of opportunity in public appointments - which says: "Nothing in this article shall affect the operation of any law which provides that an incumbent of an office in connection with the affairs of any religious or denominational institution or any member of the governing body thereof shall be a person professing a particular religion or belonging to a particular denomination."

The court said the provision "protects the appointment of archakas from a particular denomination" under the Agamas (tenets) of a temple. "All that it does and says is that some of the Agamas do incorporate a fundamental religious belief of the necessity of performance of the pujas by archakas belonging to a particular and distinct sect/group/denomination, failing which, there will be defilement of deity requiring purification ceremonies."#"Surely, if the Agamas in question do not proscribe any group of citizens from being appointed as archakas on the basis of caste or class, the sanctity of Article 17 or any other provision of Part III (fundamental rights) of the Constitution or even the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, will not be violated," Justice Gogoi said.

The court pointed out that Hinduism, as a religion, incorporated all forms of belief without mandating the selection or elimination of any one. It is a religion that has no single founder; no single scripture and no single set of teachings. It has been described as Sanatan Dharma (eternal faith), as it is the collective wisdom and inspiration of the centuries that Hinduism seeks to preach and propagate, the court said.

"While the right to freedom of religion and to manage the religious affairs of any denomination is undoubtedly a fundamental right, the same is subject to public order, morality and health...further, such rights will not prevent the state from acting in an appropriate manner in larger public interest as mandated by both Article 25 and 26 (right to practise one's religious beliefs and the right to manage one's religious affairs)," the bench said.

Hence, the court said, "appointments of archakas will have to be made in accordance with the agamas, subject to their due identification as well as their conformity with the constitutional mandates and principles as discussed above". Dalit presides over the unique traditions of a Krishna temple in Gujarat

A Dalit presides over the unique traditions of a Krishna temple in Gujarat.

UDAY MAHURKAR November 10, 1997

ISSUE DATE: November 10, 1997 UPDATED: May 17, 2013

Jhanjharka town in Ahmedabad district of Gujarat is no place for prophets of doom. They will find no stories of caste war and religious hatred here. Indeed, it is a town so convivial that in some ways it is boring.

For the prophets of peace though, this is a town of great fascination, always worth visiting. And not just because of the social amity that has existed for generations. But because of a temple that is perhaps like no other in this country.

To put it simply, Maharaj Baldevdasji, the resident priest of the Krishna temple, is not a Brahmin. Defying all tenets of Hindu tradition, the temple is headed by a Dalit. Amazing, because untouchability still persists in rural Gujarat.

It is, therefore, an unusual sight to see Brahmins, Rajputs, Banias and the powerful Patels congregating at the temple and reverently touching Baldevdasji's feet. There is no rancour here, just the simple acceptance of the fact that for two centuries, the head priest of the temple has been an untouchable.

And the feeling has percolated down to other sections of Jhanjharka. "Thanks to the influence of the temple, this area is completely free from caste discrimination," says Balwantsinh Jhala, a Rajput farmer. "Baldevdasji is the spiritual guide for many members of the upper castes." All manner of people come to worship at the temple, and the poor never return without a good meal.

"We continue to hold the view that the way to God is through the stomach of the poor and the hungry," says Baldevdasji, whose forefather served God by feeding people seven generations ago. Around 500 people have free meals at the temple every day.

The Gujarati New Year's Day, which falls on the day after Diwali, is an especially happy occasion at Jhanjharka. For the 30,000 devotees who flock to the temple that day, it is an experience in social harmony. The celebrations may consist of Hindu rituals, but it is a Muslim who kicks off the day's proceedings.

Rukmuddin Mohammad arrives at the temple early in the morning with a band of Muslims and a troupe singing bhajans. He is received at the gates by Baldevdasji. After the welcome, Mohammad climbs up the flagpole in the temple complex and hoists a white flag stamped with Islam's crescent. Only then do other programmes follow.

Mohammad is not just a randomly chosen Muslim. He is linked to the temple, and Baldevdasji, by history. The tradition of the white flag harks back to the British times when Mohammad's ancestor, an officer in the government's revenue department, became a devotee of Baldevdasji's forefather, Savgun Maharaj or Savaiyyanath, the first Dalit priest of the temple.

Acrimony between the Hindus and the Muslims has not diminished the commonality that these two have found in a temple. "For me it is a question of faith and tradition. I am proud of it," says Mohammad.

Savgun Maharaj, whose life is the subject of bardic perorations now, was buried in 1830 at the spot where the temple stands today. Legend has it that the spiritually inclined Maharaj met a Vaishnav saint called Tulsinath when still a kid. He received religious instruction from him.

The head priest of the Krishna temple is an untouchable, but brahmins, rajputs, patels and even muslims revere him.

Later, Maharaj and his wife Meghama began to be regarded as saints for the work they did during the droughts that regularly plagued the region.

The two would sell the crop that grew on their farm and use the money to provide meals for the starving people. Their innate goodness was such that they spared no effort, even walking for days, to take food to the drought-stricken.

Maharaj's great-grandson Govindramji built a fortresslike haveli and installed within the small Krishna idol that had been given to Maharaj by Tulsinath. It was only in 1981 that Baldevdasji built a more conventional Sikhara style temple there.

High caste devotees, a Dalit priest and Muslim connections - Jhanjharka seems to have been caught in a time warp. It is incredible, yet at the same time, it is a reminder that all is not lost for our fractured society.

Dalit priest Phalahari Suryavanshi Das performs the daily rituals at Mahavir temple in Patna. Photo: Indranil Bhoumik/Mint

Dalit priest Phalahari Suryavanshi Das performs the daily rituals at Mahavir temple in Patna. Photo: Indranil Bhoumik/Mint Photo: Rahul Chandran/Mint

Photo: Rahul Chandran/Mint.jpg)